The social distancing resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic has encouraged us to seek new ways to socialise and communicate with our friends, colleagues, and loved ones. From online catchups for work and social gatherings, to hosting quizzes in living rooms, many have benefitted from advances in technology and video-conferencing platforms to overcome the burdens of isolation and social distancing. In some cases, this crisis may have brought families and friends closer together; for others, however, being isolated can have extreme consequences for wellbeing and mental health.

The pandemic draws into sharp relief the fact that solitude and sociability are not simple opposites. Yet it also raises the question of how people of the past, without the benefits of modern technology and telecommunications, were able to remain sociable when physically distant from their intimate acquaintances.

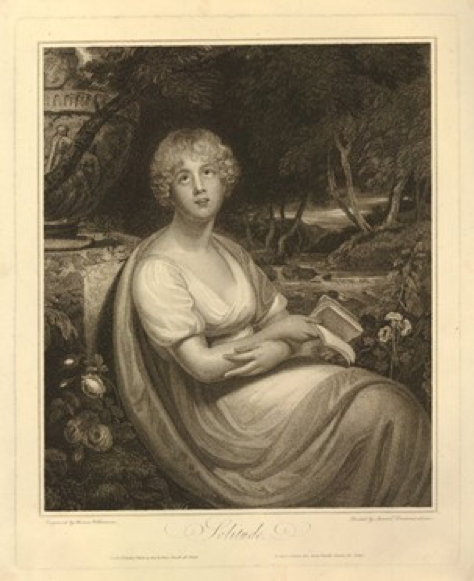

In my work on the gendered experiences of solitude and sociability in the 17th and 18th centuries, I often contemplate the emotional, psychological and physiological impact of domestic solitude.

This was a time when face-to-face contact was central to how society functioned, where life was lived with an expectation to follow others’ care and guidance.

The act of an individual removing themselves from the community that surrounded them could have important social and emotional implications.

My work considers how different stages of the lifecycle shaped how men and women encountered and understood the time they spent alone. Marriage, for example, signified a crucial turning point for all, and could have profound implications for how solitude and isolation were experienced.

For women, this was also the moment when they relinquished not only their legal and civic identity to their husbands, but also a great deal of their social independence. This meant that decisions about how they spent their time, and with whom, were frequently out of their control: their sociability was often dependant on forging connections with their husband’s business associates, or kin, rather than with the friends and acquaintances of their youth.

Indeed, as historian Katharine Glover writes, whilst marriage might provide agency and autonomy for some women, it could also be

‘a restrictive and at times lonely experience for those whose married homes were country houses far from their family or other female company’.[1]

After all, with marriage came domestic responsibility, which prevented women from undertaking visits to the houses of friends and family elsewhere in the country, which they were often able to do as spinsters.

Establishing new friendships, moreover, took time. Many newly married women acutely felt the lack of female companionship to which they had become accustomed in their youths. When Alice Thornton married in 1651, she described how marriage had placed her in a situation ‘soe remote from all my owne relations and freinds’. But more than this, her very salvation was at stake, since this arrangement surrounded her with individuals who did not belong to the Church of England, for the family of ‘Mr Thornton’s father beeing all strict papists’. She linked her ability to remain steadfast to her faith and endure the malice of her new acquaintances and relatives to the will of God, who ensured that she could ‘stand my ground in a strange place, and amongst strange people’. Thornton trusted that divine intervention would enable her to endure the trials that her social isolation had brought about.[2]

Lady Anne Dormer, a gentlewoman from Oxfordshire, had a particularly complex relationship with both sociability and solitude following her unhappy marriage to Robert Dormer in 1668. Separated from family and friends, Dormer had little company and was adjusting to married life within a busy domestic environment. In 1685, in one of the first of many revealing letters to her sister, Lady Elizabeth Trumball, she extolled the emotional and domestic benefits of her private closet, ‘a safe shelter’, where she could read and write in privacy. She contrasted this with the chaotic and overbearing domestic situation ‘out of it’, where she could find ‘little quiett’.[3]

She attributed this lack of domestic solitude to her relationship with her tyrannical husband, Robert, who was violent, abusive, and easily provoked. As a respectable gentlewoman she attempted to maintain the hospitality, social visiting, and metropolitan sociability expected of a woman of her rank. Yet, Anne confessed that her married state had altered her views on time spent in company.

‘I bless God’, she wrote, that ‘I find more true joy in one day when I am quite alone then ever I did in the heighth of my youth when I wass in the midst of jollity’.[4]

When she reflected on the social visits she and Robert made to London early in their marriage, she lamented how his continual rudeness and public shaming had encouraged her to actively shun company and seek refuge at home. In one letter she commented that if Robert failed to be ‘sivell to me at home, then Ile [not] venture abroad with him’, noting how ‘I can more easily beare a private affront than a publick one’.[5]

Perpetually poised between a love of being alone and yearning for company, Anne Dormer’s unhappy domestic situation had a significant impact on how she came to understand and express solitude. Dormer thus used her letters to her sister as a kind of surrogate for the lack of companionship she was experiencing within the household.

‘In relating many things that pass here’, she explained in one letter to her sister, ‘the only pleasure I have is in this taulking to my deare friends that make me happy in the midst of misery, for now I see not a creature in severall monthes, most being removed and indeed have no company’.[6]

Like Alice Thornton, she put a great deal of her hope in the careful watchful eye of God, to whom she expressed her thanks that:

‘I do not repine … nor find any want of company, neither am I the least melancholy, but the more I am alone the more I love to be so, and the more time I gett to my self the greater advance I hope I make in correcting my follies, complying with my difficulties and improving my self in those vertues, which I am aiming at’.[7]

Dormer’s withdrawn and solitary state, thus led her to cherish the epistolary relationships she was able to maintain, even if they were only imagined rather than physical encounters.

At the other side of the lifecycle, loss of a spouse might also trigger a significant sense of isolation and lack of companionship. In adjusting to life as a widower, the shopkeeper Thomas Turner expressed a real sense of gloom at the loss of his wife Peggy in 1761, often noting her absence after a busy day of work with no one at home to whom he could unburden his troubles and concerns.

On one occasion in October 1762 he remarked that lack of trade and money had brought severe feelings of isolation, with ‘hardly any friend in the world that can or will be a friend to me … which daily brings to my mind the memory of that sincere and virtuous friend whom I have not, my wife’.[8] At another time, when trade in his shop had been particularly slow, he spoke of how his lack of female companionship had severely hindered his sociability. Indeed, a combination of ‘want of the company of the more softer sex and … overmuch confinement’ at home had caused him to become so socially awkward that:

the want of those advantages which flow from society and a free intercourse with the world and a too great delight in reading have brought my mind to that great degree of moroseness that it is neither agreeable to myself, nor can my company be so to others.[9]

Bereavement and grief thus altered how Turner encountered and understood the time he spent alone. When combined with a lack of work and industry, Turner felt that this seriously affected his ability to remain sociable and, above all, to be agreeable when in company.

It is hard to predict how patterns of sociability and solitude might change post-COVID-19. Will we cherish our domestic solitude more, or shun it altogether? And whilst we cannot map our contemporary experiences of solitude onto the past, it is useful to think about how individuals like Alice Thornton, Anne Dormer and Thomas Turner spoke about, overcame, and experienced domestic solitude.

Their stories offer some interesting parallels to many of the challenges that we are currently facing, including severe isolation following a the loss of face-to-face contact with close friends and relatives; marital violence and abuse; loss of a loved one; and lack of employment or loss of work. And whilst their stories do not provide a solution, they do underscore how closely intertwined sociability and solitude really are, and the necessity of both to providing a sense of self-worth and wellbeing in our everyday lives.

[1] Katharine Glover, Elite Women and Polite Society in Eighteenth-Century Scotland (Woodbridge, 2011), 22.

[2] Alice Thornton, The Autobiography of Alice Thornton of East Newton, County York (Durham, 1875), 213-5.

[3] British Library, Add MS 72516, Trumball Papers Vol. CCLXXV-CCLXXVII. Letters of Anne Dormer, 159, 28 August 1685.

[4] Letters of Anne Dormer, 193, 3 November 1687.

[5] Letters of Anne Dormer, 163, 24 August [1685].

[6] Letters of Anne Dormer, 199, 2 January 1688.

[7] Letters of Anne Dormer, 201, 28 January 1689.

[8] Thomas Turner, The Diary of Thomas Turner, 1754–1765, ed. David Vaisey (Oxford, 1984), 30 October 1762.

[9] Thomas Turner, Diary, 10 November 1763.

Naomi Pullin (@naomipullin) is a Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellow and Assistant Professor in Early Modern British History at the University of Warwick.