‘In solitude the imagination bodies forth its conceptions unrestrained….’

(Mary Wollstonecraft, 1796)

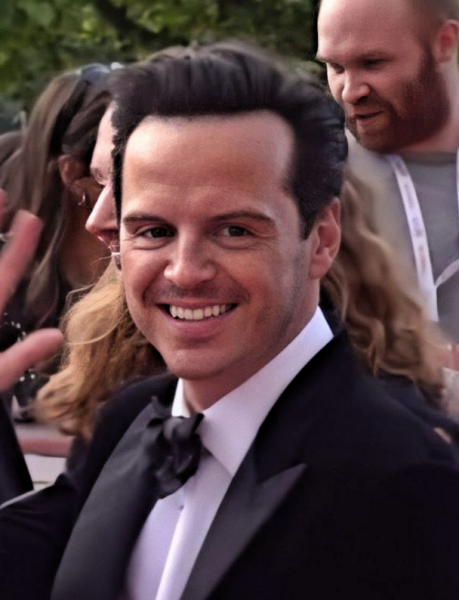

I want to be Andrew Scott’s mother. By ‘Andrew Scott’ I mean the award-winning Irish actor who played the hot priest in Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag. By ‘mother’ I mean mother, although Scott has a perfectly good mother already (Nora, a former art teacher). By ‘want’ I mean I desire to be Scott’s mother because in this mad pandemical world the line between the feasible and the fantastical has dissolved. Ordinary pleasures of a year ago – dinner with friends; going to a concert; cuddling a grandchild – have become impossible dreams. So why not dream the impossible?

I’ve never met Andrew Scott. I think he’s a terrific actor: I loved him in Fleabag and everything else I’ve seen him in. In September he gave an in-camera performance at the Old Vic of Three Kings, a one-man play written for him by his former partner, Stephen Beresford. The play was scheduled for July 31st but a few days before I got an email saying it was delayed by Scott’s admission to hospital for ‘minor surgery’. No details, except the issue was ‘not serious or COVID-related’. In early August I received another email saying Scott was still not well enough to perform.

The weeks passed and I became anxious. My younger stepson works at the Globe; one of his closest friends is a top director. His husband is a novelist who has written for the stage. Their world is full of thesps: could they find out what was wrong? No. I fretted more. I asked some friends connected to the London theatre world. No joy there either.

In early September Scott performed Three Kings, to rave reviews. I searched his face, was he really alright? By now it’s fair to say that I was Scott-obsessed. I viewed online interviews, checked out his personal history, re-watched him as the hot priest. Adorable.

I’m not given to infatuation with performers; Elvis in G.I. Blues was the last. But I know infatuation when I feel it. This was something different. It took me time to name it. It was mothering-hunger.

I’m not a mother. But I’m rich in stepsons, nieces and nephews, godsons and goddaughters, and now two grand-godchildren, born during the pandemic. My wife has four living siblings, with dozens of children and grandchildren between them. My COVID world is full of next-generation family.

But I’ve become greedy. I want to add Scott to the mix, I want him as my boy (he’s 44, I’m 70). My family will love him, and he’ll fit in well. Thespianism? We’ve got that covered. Queer? Yep, we’re good there. Irish? My older stepson teaches philosophy in Galway. Celebrity? One of my brothers-in-law is a famous haircutter; in recent interviews Scott reminds me of him, the same well-rehearsed casual charm, the open shirt, the finger-tossed hair. Another brother-in-law is a leading stunt director; for all I know Scott may have worked with him. So he will be right at home with us.

So why not? Desire is never reality-bound. And when desire confronts disease and death it can blaze up, reaching out to life, insisting on it, demanding more of it. I want Scott because he is more of what I already have. But my son Scott also represents what I will never have – a son of my own. Not once, in all my decades of childlessness, have I hungered for motherhood as I do now, to love a life born from me, now that death is everywhere around me.

Globally COVID-19 has claimed two million lives and rising. The UK’s death rate is one of the highest in the world. One friend has died from it, another has been severely disabled. People who lose loved ones to other diseases cannot come together to mourn them. My wife lost a brother to oesophageal cancer during the first lockdown. The same disease killed a close friend of mine in early December. He lived in Toronto and his partner is my oldest friend. I should be there with her now. What hellish fate has stuck me here in London while my dear friend mourns far away? A misery of separation that I’m sharing with thousands of others across the globe. My widowed friend has two sons who cannot put their arms around her. My stepsons and I cannot hug; we might kill each other. Love and death in close embrace: an eternal theme of literature, art, drama – now made a quotidian reality.

Life revolts. Fleabag shows a young woman seesawing between sexual encounters in the wake of her mother’s death and the suicide of her closest female friend. Finally she falls in love with a Catholic priest (Scott) who chooses God over her. Death has sent her careening toward the impossible. At one point, to cover for her sister’s miscarriage in the middle of a fraught family outing, Fleabag pretends that she’s miscarried. For her, there never was a baby. But it’s the priest’s ‘beautiful neck’ that she finds irresistible. Scott does indeed have a good neck, but who cannot find a baby’s neck irresistible?

Passionate sex after funerals is a well-known phenomenon. Female sexual desire is said to have increased during the pandemic. But eros takes many forms. Child-yearning, as Lucy-Hughes Hallett labels it in Peculiar Ground (2017), can be as exigent as lust. Will there be a baby-boom in the wake of COVID? Not for me; and anyway it’s not baby-mothering I want but a gorgeous actor-son who exudes playful vitality.

In interviews Scott repeatedly describes acting as playful. He loves Picasso’s famous remark that ‘It took me my whole life to paint like a child’. I don’t know if Scott has ever read the psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott, but for Winnicott play is the life-force. Play, in children and adults, is where dreams are enacted, where fantasy and desire find creative expression. In play, people become themselves, for good or ill, and this is exciting, joyful, dangerous. When Scott played Hamlet in 2017, he surprised audiences by showing the young prince as full of fun. Why this portrayal?

If you don’t understand that Hamlet had a great joy for life, if you think that for the length of time that he was on the earth he was always depressed, well the release from life isn’t really that tragic…[but] If you think it was somebody who was full of life, and engagement, and fun, that has now just been totally sucker-punched by grief and doesn’t want to be alive anymore, I think that’s much more telling, and much more of a consuming story. (Evening Standard, 26.11.19)

Sucker-punched by grief…an image for our times. So how do we go on playing in the face of disease and death, and fear of death? We reach out for what we have; we dream of what we want. Scott’s emergency surgery, back in July, triggered a new dream in me. Anxious for him, I clutched fearfully at what I already have – the family and friends I love – and conjured up an ideal supplement: a fantasy-son, fully recovered, to accompany me through this dark time to a play-filled life beyond.

*

A note on this blog:

Solitariness breeds fantasy. This has been a truism since antiquity. Meditating alone, the Roman philosopher-emperor Marcus Aurelius was visited by ‘fancies’. Christian hermits and medieval anchorites saw visions. The sixteenth century essayist Michel de Montaigne, sequestered in his tower room, rode the ‘wild horse’ of his imagination. Jean-Jacques Rousseau wandered alone through natural landscapes, full of ‘ecstatic reveries’. Romantic solitaries soon followed his example.

But what about now, as millions live in enforced isolation? The COVID pandemic, with its terrible toll of death and loss and longterm illness, has inflicted misery worldwide. Social distancing and lockdowns have created new levels of solitariness which many find excruciating. But this solitude has also given free rein to fantasy.

Here we are posting a series of ‘Lockdown Fantasies’ showing how pandemical solitariness plays on the imagination. This is the first. Come back for more, and dream your own.

Barbara Taylor is Professor of Humanities at Queen Mary University of London and Principal Investigator on the ‘Pathologies of Solitude’ project.