Hetta Howes: So who was Sam Selvon and who are the characters that he’s exploring and presenting to us in the novel?

Susheila Nasta: Sam Selvon was one of a group of major Caribbean writers who came to London during the 1950s or just before. Amongst them were people like George Lamming (with whom he travelled by chance on the boat where they fought over a typewriter as they both tried to finish their first novels), V.S. Naipaul, Wilson Harris, Andrew Salkey, Roy Heath. There were a whole group of them, but they didn’t actually come as a group that knew each other because they came from separate islands.

Sam Selvon was an East Indian Trinidadian who’d actually worked as a journalist in Trinidad before and during the war. He had started writing pieces in the Trinidad Guardian under various pseudonyms and had some of his poems and short stories read out on a major BBC program called Caribbean Voices. This is where many of these writers met for the first time, earning tiny bits of money for the broadcast which went back across the seas to the Caribbean.

The Lonely Londoners is based on the people Selvon met and the stories he heard living in London. It’s about being a newcomer to the city as well as being a black migrant. In fact there’s a passage at the end of The Lonely Londoners when the main character, Moses, has really begun to feel like he’s had enough of the repetition, of listening to the same sorts of stories from newcomers as they arrive at Waterloo. He’s heard it all before.

There’s a constant sense of movement in the stories the ‘boys’ tell about the city; it’s a new world they’re just discovering but they end in a sort of bleakness. I suppose any new arrival in a city may seek out and meet people in similar situations, in a hostel or a hotel where they try and bond through recounting stories of their encounters. Sam Selvon calls these stories ‘ballads’ and with all ballads the stories operate on a number of levels, creating a sense of community in an alien and alienating world but also a deliberately inflated sense of a false confidence and bravado.

HH: I think the loneliness in Selvon’s writing feels quite unique. You’ve got this real sense of community and busyness, lots of voices crowding in on the reader, but then real flashes of isolation. In what ways are these lonely Londoners lonely or solitary?

SN: There’s so many layers to the loneliness and actually, it’s really important that it’s called The Lonely Londoners and not ‘The Black Londoners’ or ‘The Black Lonely Londoners’, because I think Sam is really pointing to a much broader sense of atomisation in a modern city just after the war, a city trying to pick itself up. He’s not only talking about black characters, although, of course, they are the dominant figures. But he is also talking about the Poles. He’s talking about women who have lost their husbands in the war. He’s talking about poverty and he’s talking about London streets and all of these rooms, as he says, kind of pushed up against one another, where people don’t even know what they’re doing next door.

So there’s a broad sense of a kind of modern exile which is very real for the migrant and especially in the hostile environment of postwar London, the black migrant. At the same time, his London is also much like T.S. Eliot’s city, it’s an ‘unreal city’.

So, to return to questions of loneliness, the characters in the novel are lonely first and foremost because they were colonial migrants. They had imagined the mother country was going to embrace them and welcome them. But in fact, what happened was they became alienated. They didn’t really know at first why they were alienated. There’s a very good scene in the novel where Galahad, who’s christened Sir Galahad when he arrives in London – before that he’s just an ordinary man from the Caribbean named Henry Oliver, he’s kind of reborn – is going out for the first time. He strides about like a lord, as if he’s in Trinidad in a small place where it’s sunny. But standing outside the Tube station, he discovers that he’s absolutely terrified that the sun in the sky doesn’t look anything like any sun he’s ever seen before and he’s alone. He’s alone in this huge metropolis and he hasn’t got any money and he hasn’t really got anywhere to live.

And later, you have that whole issue of loneliness, again represented through Galahad, as the colonial going to Piccadilly to see Eros.

You know, he’s excited, he’s out in the big city, centre of the world, going to meet a girl, but then he also meets a child who stares at him aghast because he’s black. Later, when he gets home, the reality hits as he looks at the colour of his hand and says, ‘it’s you that’s causing all this botheration’. So it’s a kind of loneliness that’s both individual in terms of these black migrants who can’t find work, who are broke, who’d expected to come to the ‘real’ world when in fact, they’re in an unreal world. But there’s also this broader sense of them seeing their own blackness through the eyes of others, of facing racism and recognising that as a kind of ethical loneliness.

HH: Yes. I mean, I was struck by that passage as well – I think where he says his sun is like an orange.

SN: A force-ripe orange.

HH: It’s such a striking image. This uncanny sort of unreality. But also, as you suggested, perhaps being caught between two worlds?

SN: That’s right. It’s the island and the city. And of course, if you read the whole of Sam Selvon, he didn’t just write about London, he wrote about Trinidad too, he’s writing about the island and the city.

HH: Yes, absolutely. And you’ve got the island in the city, as you say, but also this sense of worlds within worlds in London. I’ve got a quote here from Selvon, who describes London at some point: ‘divide up into little worlds and you stay in the world you belong to and you don’t know anything about what’s happening in other ones’. So there’s this sense that London is quite divided. Is there more world-hopping going on than we might think? I felt, reading it, that there is a real sense of division, but also of crossing of these world barriers as well.

SN: Absolutely. In fact, one of the privileges his boys have (and ‘the boys’, is obviously deliberate, they’re kind of innocents abroad, they haven’t quite matured in the city) is that there are these lock-up worlds which many of the British are in, but one of the privileges the boys have is that they coast the lime, they go round the city, they travel at night, they work in the night.

Although they create little areas for themselves, which are kind of West Indian, Caribbean areas (and he mocks that city very carefully in the novel), they also traverse those borders. And there’s this very delicate shift in the way in which he portrays his boys, between this almost stereotypical cardboard cut-out element of these characters and their actual real lives. And it’s only towards the end of the book that we start to realize that Bart, who’s constantly searching for his girlfriend, Beatrice, is like a fantasy figure from a Dante-ist purgatorio.

And then there’s Moses, a prophet in the wilderness, whose voice by the end (as both narrator and participant) begins to shift as he stands apart from the group and you start to get a new voice of a writer emerging, separate from the scene that’s being described. But this is not only a black story; the loneliness is very much part of a wider modernist vision. Moses is like a flaneur. He walks the city at night and like Selvon himself, he carries and transports the stories.

HH: Yes, and particularly at night, when the flaneur can see a slightly different world and perspective to usual. Some of the characters seem more successful than others at navigating the new world. And one, for example, is the elderly aunt Tanty, who manages to persuade a London grocery shop owner into opening a line of credit for her, which is something that had been common practice for her in the West Indies, but not so common in West London. You’ve described the novel in your introduction to the most recent Penguin Classics edition, as a colonization in reverse. I wondered if you might say a bit more about that idea.

SN: I suppose one needs to return to the issue of language and culture – and of course, it’s the language that makes the culture – Tanty does colonize in reverse by trying to establish customs that make the world familiar, that were part of her much smaller world in Trinidad or Jamaica. She does this through food, through banter, behaviour. But I think the ‘colonization in reverse’ idea is much broader than that. There’s a very famous Louise Bennett poem, which begins: ‘What an awful news, Miss Mattie / My heart gonna burst. / Jamaican people coming, / colonizing England in reverse’. That’s where I’ve taken the line from.

It’s a kind of ironic parody: look at all these people says Selvon, everyone’s worried (and we still have this now of course) all these immigrants coming in, overcrowding the place, but the joke is actually, they’re going to turn Britain into something else, which they have done, of course. So Selvon is exploring how the language can both make and colonize a city and what he does by creating these ‘ballads’, through creating this Caribbean literary vernacular, is to recreate the city through the eyes of the new people that are living in it. And, of course, that kind of reinvention and recreation or reimagining of the city is absolutely critical to their survival.

I suppose to go back to Tanty she wants to be able to buy what she needs in the grocery shops, it’s like what you can buy easily in Deptford or Brixton and elsewhere in the city now. Food is important and she was making sure she got the things she wanted to buy, what she wanted to eat.

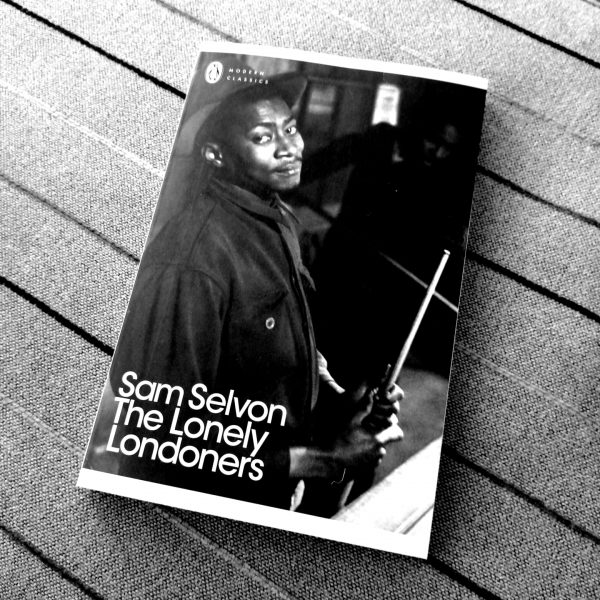

HH: I’m really glad you brought up language, because I’ve read that Selvon originally tried to write the novel in a standard English and then gave up and changed it to a sort of Creolised English that we get in the novel. I honestly can’t imagine it being written any other way. How important is that sort of stylistic decision in bringing out the experience of the lonely Londoners?

SN: It was absolutely critical because he closed the gap between the teller of the tale and the tale itself. Otherwise what you have is a standard English-speaking narrator and so-called ‘dialect-speaking’ characters, which implicitly creates a distance. When I used to teach The Lonely Londoners or talk about it in many, many different contexts, so many people were surprised to learn that Sam Selvon spoke standard English. It was almost always, doesn’t he speak like this? And you think, well, no, this is a strategy he used to write the characters in this book. He started writing it in the States on a residency when he was distanced from Britain – and that’s where he made the decision to write in this creolised version of the Trinidadian vernacular, which would be readable by anybody. He always said it was like being transported or sitting in a bus; the language took over and the writing took off once he’d made that decision.

I think the modified version of Trinidadian English he creates really draws a lot on the tradition of calypso: a form of oral political satire or what was called a kind of piquant humour, which works on deflation, inflation and humour. Most calypsos are ballads! In fact, the pathos of the book is heightened by this tension in the language: between inflation and deflation. These black migrants are invited to the city, it’s a city supposedly where the streets are paved with gold but they soon hit the realities of an almost nightmarish, purgatorial existence where they’re forced to live in basement rooms, surviving the damp, the darkness, the greyness and where no one knows what X or Y or Z is doing.

HH: Yes, we’ve talked quite a lot about loneliness and I’ve brought up some of the moments of the novel that stuck with me or were more poignant, but it is really funny as well. I mean, dark humour for sure. A particularly bleak moment is the bit where Cap is desperate for something to eat and he sees some seagulls sitting on the ledge and decides he’s going to try and catch one. It’s a really funny scene but it’s a really tragic scene as well. You’ve called it tragicomedy in your introduction [to the 2006 Penguin edition] and I think it’s perfect. I think that humour and the language together feel like the best way to immerse a reader in my experience.

SN: And he’s taking the mickey out of the old lady in her fur coat in Kensington Gardens with Flossie, her dog, while they’re all similarly trying to catch pigeons. The pathos of that situation where they’re desperate to eat and make a good Trinidadian curry, but she thinks they’re behaving like terrible black men. I think the humour, the empathy and the breadth of vision is why the book has remained in print ever since it was published.

It speaks to all sorts of different audiences. And it says very complicated things in quite a direct way, which doesn’t simplify them.

HH: Certainly. It might have been written over 60 years ago, but this novel feels very relevant to today, doesn’t it?

SN: It certainly does and in a number of ways. Not least through the stories of today’s migrants and refugees attempting to make a life in Britain. And the question of forgotten histories too, how black and Asian migrants in the post-war period were so formative in the making of Britain. People are only just beginning to recognise how black writers have long challenged issues of social and political justice and Selvon’s novel was prescient.

At one moment in The Lonely Londoners, he flags how the ‘sweat and labour’ of his migrants (echoing the longer history and atrocities of the slave trade) had built the city. This moment from the book was used in the 2018 Windrush exhibition, held at the British Library, a couple of years ago. Ironically, it celebrated 70 years, at the very same moment as the injustices of the ongoing ‘Windrush Scandal’ came to light. And right now of course there is the Black Lives Matter movement as well as the disproportionate suffering of the BAME community with COVID.

It seems incredible that we are still party to a similar discourse: whether around migration, race and Brexit. Conversations that Sam was already so conscious of when he first attempted to subvert that vision of Britain in The Lonely Londoners.

Susheila Nasta (@susheila_nasta) is Professor of Modern and Contemporary Literature at Queen Mary, University of London and the Founding Editor of Wasafiri, the Magazine of International Contemporary Writing. She is a friend of Sam Selvon, a critic of his work, and continues to act as literary executor of his estate.

Hetta Howes (@HettaHowes) is Lecturer in Medieval and Early Modern Literature at City University of London.

This discussion took place as part of our ‘Spaces of Solitude’ podcast series, which you can listen to here.