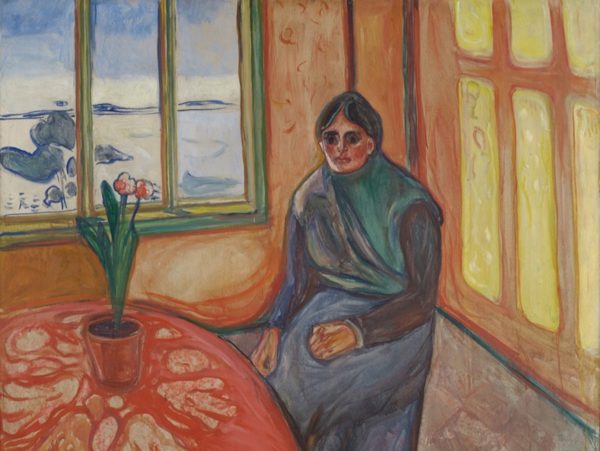

Since the time of Galen, physicians have identified solitariness with a panoply of morbid states – gloom, fear, anxiety, religious delusions – known collectively as ‘melancholy’. Like present-day clinical depression, melancholy was both physical and psychological. The relationship between mind and body varied between period and medical authority, but solitariness was always implicated. ‘Be not solitary, be not idle’, the Oxford don Robert Burton counselled in his compendious 1621 The Anatomy of Melancholy, for ‘such as are solitary… are most subject to melancholy’.

Pre-modern melancholy also had a positive variant in ‘white’ melancholy: a life-enhancing, contemplative state aligned to emotional sensibility and creative genius. But by the end of the 19th century, ‘white’ melancholy has disappeared and ‘melancholia’, as black melancholy had become, developed from a target of 18th-century emergent psychiatry to become a psychiatric disorder characterised by anxiety, morbid preoccupations, guilt and a ‘love of solitude’.

‘Clinical depression’ subsequently took over from ‘melancholia’, with biomedical interpretations of the disorder vying with socio-cultural and psychoanalytic accounts. Solitariness continued to feature as a key factor in severe depression, and since the mid-twentieth century, there has been a flood of scientific research into the mental health toll taken by social isolation and loneliness, especially in terms of depressive illness.

Further reading

- ‘Literature and Landscape in the Eighteenth Century’ – article by Stephen Bending (2015)

- Faces in the Water – novel by Janet Frame (1961)

- ‘Mourning and Melancholia’ – essay by Sigmund Freud (1918)

- Melancholy Experience in Literature of the Long Eighteenth Century – book of essays edited by Allan Ingram, Stuart Sim, Clark Lawlor, Richard Terry, John Baker, Leigh Wetherall-Dickson (2011)

- ‘Acedia’ – article by Jonathan Zecher

Further listening

- ‘The long history of solitude as both a blessing and a curse’ – radio programme from The Sunday Edition, CBC Radio

Blogs

Our network of researchers frequently write posts for our blog on solitude, melancholy and depression. You can read their blog posts here.

Over the course of our project, we met regularly with our research network to discuss the themes of our project. You can read a selection of their colloquium papers on solitude, melancholy and depression here.