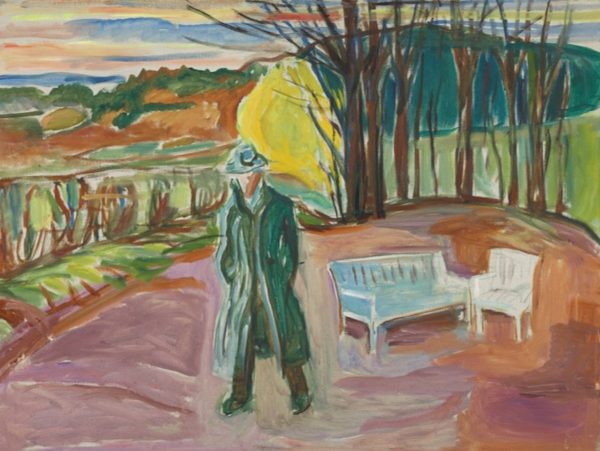

To ‘get away from it all’ is one of our most enduring yet rarely fulfilled fantasies. In discourses of mental and physical self-care, solitude is figured as a restorative practice, a means of relaxation long associated with reflective contemplation, scholarship and literary creativity. Social withdrawal may also involve a radical rejection of social convention or personal oppression, providing a point of departure for a freer way of life and the development of new sensibilities.

However, voluntary solitude has also long been pathologised and stigmatised. In pre-modern society, a pronounced preference for solitude (unless religiously motivated) was almost invariably regarded as misanthropic and condemned by Christians as a sin. Criticisms grew louder in the 18th century, as the growth of commercial individualism prompted fears about social cohesion being eroded by ‘self-love’. Sociability became the hallmark of an enlightened citizen. Jean-Jacques Rousseu’s passion for solitude saw him denounced as a ‘gloomy misanthrope’ and – significantly – as a ‘madman’.

The link between solitariness and mental illness has become much stronger with the growth of professional psychiatry. In 1980 the DSM added ‘avoidant personality disorder’ to its diagnostic categories, followed by ‘social anxiety disorder’ in 1994. Today there is widespread concern about the voluntary solitary, ranging from those with mental disorders to those who prefer to connect with other individuals only digitally to those who reject the social convention.

Further reading

- Drift: Illicit Mobility and Uncertain Knowledge – book by Jeff Ferrell (2018)

- ‘In Praise of Doing Nothing’ – article by Simon Gottschalk (2018)

- Total Loss Farm: A Year in the Life – memoir by Raymond Mungo (1970)

- Convenience Store Woman – novel by Sayaka Murata (2019)

- ‘How To Do Nothing’ – interview with Jenny Odell (2019)

- ‘Splendid Isolation’ – article by Mark O’Connell (2020)

- ‘Philosophical Solitude’ – article by Barbara Taylor (2020)

Further listening

- ‘Japan’s modern-day hermits’ – video from France24 English (2019)

- ‘One to one with hermit Rachel Denton’ – radio programme from BBC Radio 4 (2016)

Blogs and colloquium papers

Our network of researchers frequently write posts for our blog on voluntary solitaries. You can read their blog posts here.

Over the course of our project, we met regularly with our research network to discuss the themes of our project. You can read a selection of their colloquium papers on voluntary solitaries here.