Notes on Process

At the beginning of her residency, Sophie Burrows met with the Pathologies of Solitude team. These conversations became the starting point for her artworks.

Below, Sophie explores the process of creating her works, and the team thinks about how the sequences relate to the themes of their own research.

Wordless Comics

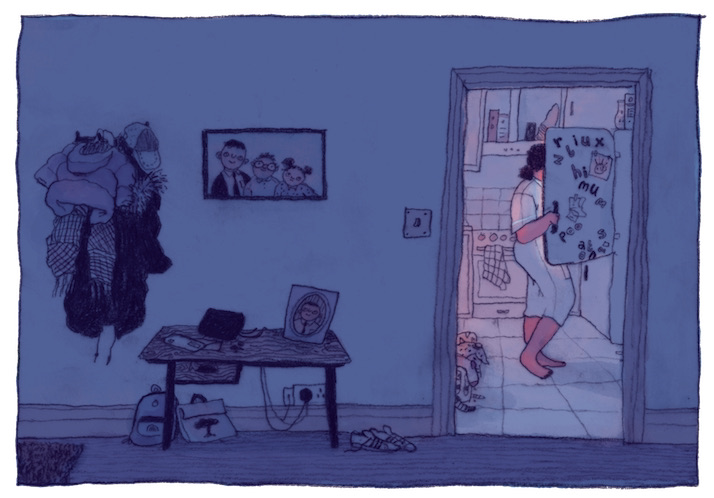

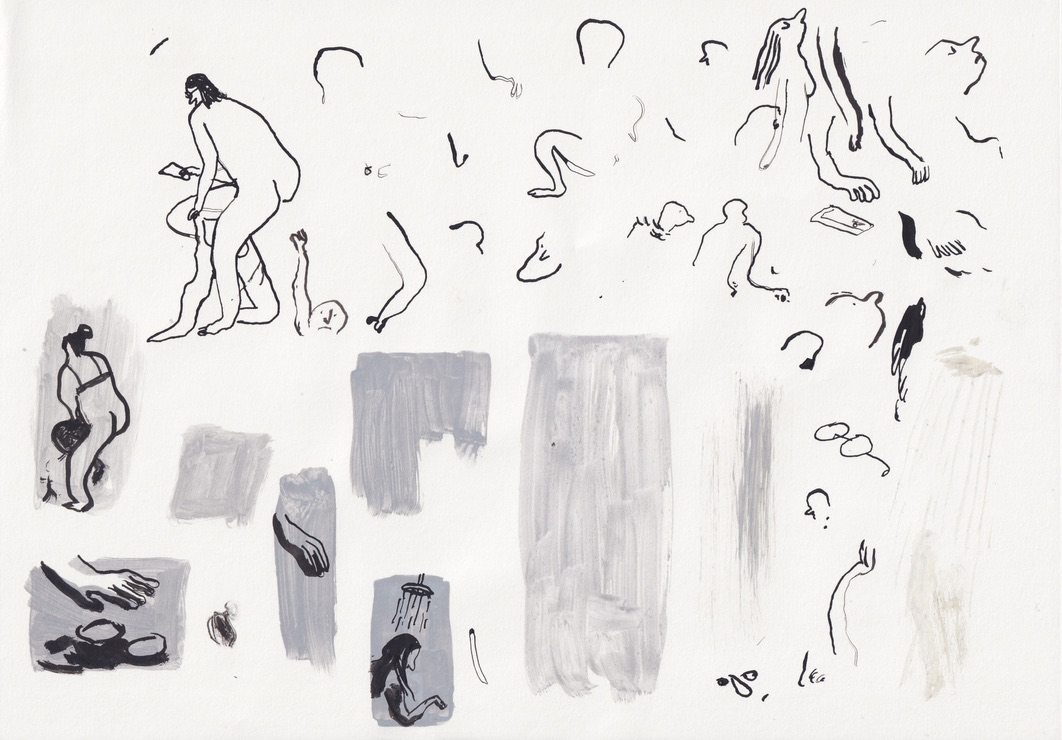

Something I love about creating wordless comics is that they can bring an ambiguity to their reading. I hope that they allow space to be interpreted in different ways, perhaps influenced by your own understanding and feelings around solitude. My approach to this project as a whole was a visual ‘pondering’- an exploration of questions. I began to make a list of questions relating to solitude; many of which the team were asking in their research, or speaking about in interviews/talks. Others were questions that I found myself asking as I read their work, thought about my own experiences, and drew these sequences. My own work usually draws heavily from observation and experience, and so the events of the past year and my own emotional responses to these were also a large influence on my drawings and the narratives that followed.

Reverie

In this particular sequence, I was wondering about the spaces we find solitude in, and whether these have shifted or changed during the pandemic. Does ‘alone-ness’ equate to solitude? What roles do nature and technology play in modern day solitude, and how have these shifted in the past year? Is finding solitude more difficult when technology is infiltrating our most private spaces? Or is it providing us with much needed connection? And of course; who are we with, when we are alone?

Alongside this, I was particularly inspired by James Morland’s research on the poetry of Thomas Gray. In his CBC radio interview, he spoke about Gray’s ‘feelings of separation from the natural systems and workings of the world’ and how it was springtime that caused him the most grief– ‘a reminder that the natural world keeps moving, and you feel separate from it’. This struck a chord with me; although he is describing grief and the mourning of loved ones, I found it echoed other situations where one might find oneself lonely or feeling isolated. Over the course of lockdown, I became fixated on a tree outside my window as it signalled the changing seasons, while indoors it felt like time wasn’t passing at all. I think many people’s relationships with both nature and technology changed over the course of the pandemic, and I’ve been really interested in exploring both of those in relation to solitude and loneliness.

Speaking with Charlie Williams and reading his blog post here encouraged me to consider our relationship with technology and how that relates to our experience of solitude. Over the past year, our devices have provided welcome connectivity to other people through the pandemic, but for many of us this further dependence on our phones has made it tougher to disconnect and stop ‘doom-scrolling’. In his blog Charlie shared his thoughts on finding joy through exploring his local area, including parks, where he was able to be ‘alone with others’.

This resonated with me as something in which I had also found comfort. Many people seemed to find a deeper connection to nature through the pandemic; perhaps as an antidote to our increasingly technology dependent lives.

Akshi Singh:

My work explores Marion Milner’s thinking about solitude. Milner was an artist, writer, and psychoanalyst. One of the things that is so engaging about her writing is the way in which she pays attention to what happens to the body in solitude. Sophie’s drawings, like Milner’s work, are also attentive to solitude as an intensely embodied experience. Given that Milner worked out many of her ideas about the psyche through doodling and drawing, I find it wonderful that Sophie’s depictions of solitude rely on images, which are without caption, dialogue, or description.

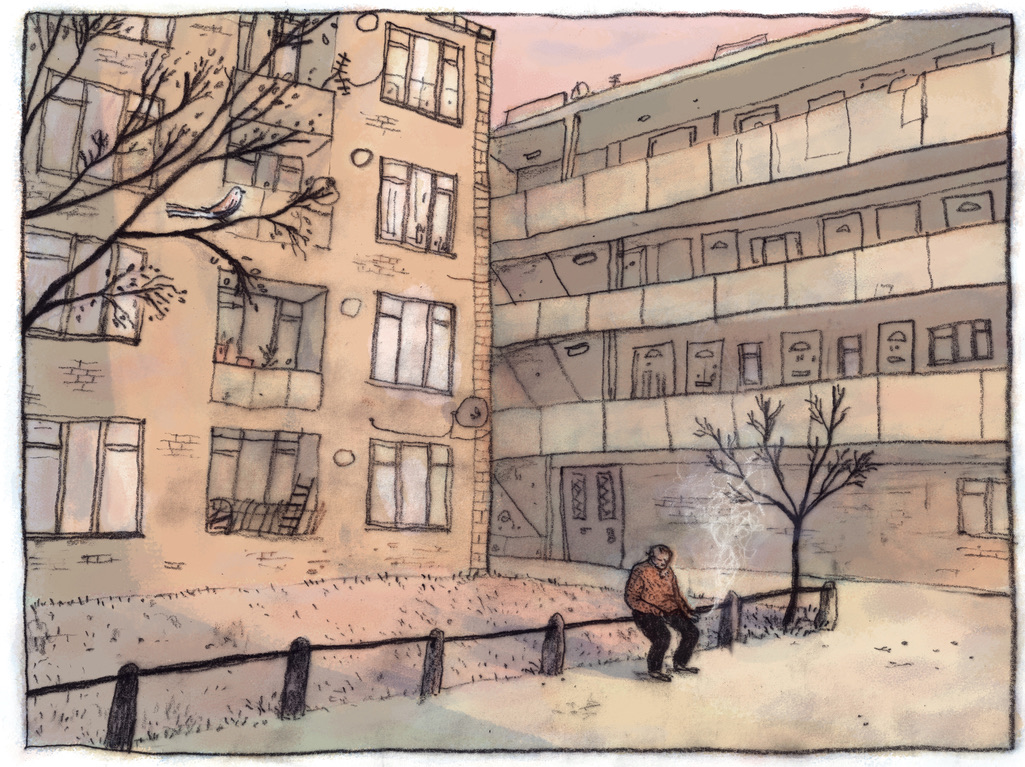

Breathing Space

This sequence evolved from thinking about the relationship between solitude and health, and how solitude can influence our wellbeing in both positive and negative ways. I was inspired by James Morland’s research considering the duality of solitude, how it can be both beneficial and dangerous to us.

Through his writing I was introduced to Alexander Pope’s ‘wholesome solitude’ that is salutory and curative, as well as John Armstrong’s description of solitude as a ‘sad nurse of care’. As the ‘sad nurse’, solitude can be nourishing but also has the potential ‘to lead to the darker consequences of too much musing’.

I was often sketching from my window through the pandemic, and I regularly saw a distant neighbour out for his cigarette breaks. As an ex smoker, I realised that there was a strong association in my mind between smoking and solitude.

This sequence evolved from thinking about the relationship between solitude and health, and how solitude can influence our wellbeing in both positive and negative ways. I was inspired by James Morland’s research considering the duality of solitude, how it can be both beneficial and dangerous to us.

Through his writing I was introduced to Alexander Pope’s ‘wholesome solitude’ that is salutory and curative, as well as John Armstrong’s description of solitude as a ‘sad nurse of care’. As the ‘sad nurse’, solitude can be nourishing but also has the potential ‘to lead to the darker consequences of too much musing’.

I was often sketching from my window through the pandemic, and I regularly saw a distant neighbour out for his cigarette breaks. As an ex smoker, I realised that there was a strong association in my mind between smoking and solitude.

I used to use smoking as an opportunity for time alone. For me, my lone smoking perhaps had that same duality always present in solitude, that power to nourish as well as damage.

I thought about how these five minute cigarette breaks used to provide me with a chance to get away from whatever I was doing, to pause and achieve some space to think. This solitude had the power to be curative, but could easily give way to ‘sickly musings’. A short break could provide much needed respite, or open the door to darker thoughts. I eventually quit smoking when many of my breaks were no longer offering opportunities to seek ‘breathing space’ but instead filled me with thoughts of the physical damage I was doing to my health through the act itself.

James Morland:

When we first started talking about the different ideas of solitude with Sophie, I mentioned how poets found it difficult to define solitude in the eighteenth century. When thinking about the relationship between solitude and health, eighteenth century poets focused on a duality: solitude can be harmful or beneficial. Throughout the eighteenth century, poets relied on the senses to evoke both universal and intensely personal experiences of solitude. For John Armstrong, solitude was the nurse of ’sickly musings’.

It was so interesting to see Sophie’s work develop and see these centuries’ old dilemmas be worked out in the twenty-first century pandemic context. Sophie’s depiction of her neighbourhood gives a sense of the mix of those personal and general experiences of solitude. Sophie has brought many of the eighteenth-century questions to bear on our contemporary contexts, thinking about what solitude does to the mind and body. Whether by re-contextualising a separation from nature through technology, or exploring solitude as productive of both wholesome and sickly thoughts in smoke breaks, Sophie’s work shows that these questions about the benefits or perils of solitude are ever-repeating.

Return

Each of us will think about solitude in a unique way. We will form our own individual opinions about it, and your experience will likely be different to my own. These differences seem to have been amplified over the course of the pandemic. From talking to others around me, I got the sense that the usual balance between alone-ness and together-ness had been tipped; homes that were usually pretty busy felt like they were bursting, while people who lived alone experienced more emptiness than usual. This sequence was made while thinking of several questions. Firsy, how different are each of our experiences of solitude? in which spaces, in what times, do each of us find solitude? How do our roles at work or in the home influence our experience of solitude?

For those of us who seldom find moments to be alone, what do we do with those moments when they come? Do differences exist between a solitude that has been ‘taken where we can get it’ and one that is more deliberate? Is solitude a luxury?

Charlie Williams:

It’s been wonderful to see Sophie’s reflections on the lockdown and the research of the Solitudes project come to life. I’m drawn to the numerous objects, particularly in the ‘return’ sequence, which signify the absence of others. It reminds me of the ways in which the challenges as well as the pleasures of being alone can often take us unawares and that the material world around us always anchors our experience of solitude. The solitary figures I look at in my research on the 1960s dropout are often conspicuous in their solitude. But Sophie’s drawings make me think that the solitary figure always invites speculation whether welcome or not.

Of course, this sequence, as the others, is an imagined experience of solitude. It is not my direct experience and, as I drew, I began to think about our perceptions of others’ solitude. How do we imagine others’ solitude to be? How do our perceptions and their experiences differ? Do each of us have expectations or parameters by which we define alone-ness as healthy or acceptable?

With this in mind, I wondered how the nurse might perceive the smoker’s solitude, how my reader might perceive the nurse’s solitude, and how my own thoughts and feelings have influenced this.

This sequence also comes back to the idea of shared solitudes. Both the nurse and the smoker are experiencing some form of solitude here, although internally this experience could be very different. Yet are they connected, simply through the shared experience of solitude?