Today billions of people across the globe are living in enforced isolation, cut off from friends and family beyond their immediate households. Many are living entirely on their own, without any recourse to their usual forms of sociability. How are people experiencing this, and what will be its consequences?

Involuntary solitude has always been a feature of human society. Disease has often been a factor. In medieval England people suffering from leprosy (Hansen’s disease, as it is now known) were stigmatised and shunned. Many were confined to leper-houses but some wandered the countryside, begging. Others, if the disease was not too obvious or debilitating, tried to carry on as normal. But they were subject to severe sanctions.

People suspected of having leprosy might find themselves legally ejected from society. In 1420 the sheriff of Lincolnshire was chastised by the courts for failing to have carried out an assessment of a Boston mercer, John Louth, who

commonly mingles with the men of the aforesaid town and communicates with them in public as well as private places and refuses to remove himself to a place of solitude, as is customary and as it behoves him to do, to the serious danger of the aforesaid men and their manifest peril on account of the contagious nature of the aforesaid disease [1].

Many other communicable diseases, most famously the bubonic plague, forced people to sequester themselves, in their case as a preliminary to almost certain death.

But seclusion was widely acknowledged to have its own dangers. From antiquity onward, people had been warned about the pathological effects of solitariness. Too much solitude was said to breed a host of debilitating symptoms, ranging from depression (melancholy) and extreme anxiety to wild fantasising and outright insanity. In 1621 the Oxford don Robert Burton, in his compendious Anatomy of Melancholy, counselled his readers to avoid solitude, for those that were solitary risked ‘fear, sorrow…discontent, cares, and weariness of life’.

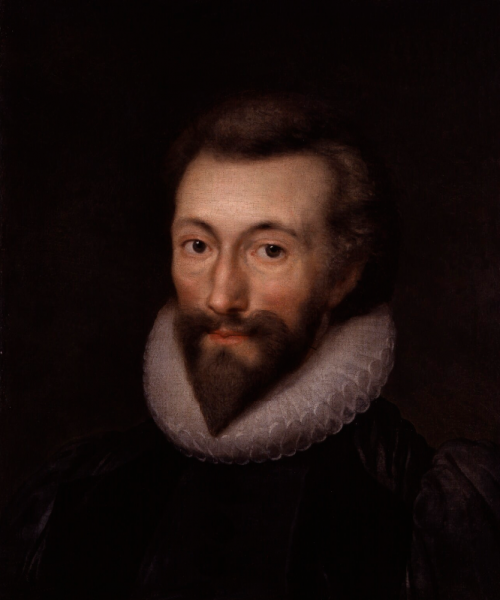

Even people whose vocations drew them to solitude were said to imperil their psychological health. The 14th century Italian poet Petrarch wrote a famous panegyric to his solitary lifestyle (De Vita Solitaria, 1346), yet even his ‘sweet solitude’ was marred by bouts of acedia, a combination of ennui and gloom from which reclusive scholars, monks and hermits were also said to suffer. Jesus counselled his followers to ‘pray to thy Father in secret’ (Matthew 6:6) but throughout Christian history solitary worship was – and remains – contentious. Here the risks were as much moral as psychophysical. As happened with Eve in Eden, Satan lay in wait for solitaries, tempting them with forbidden desires. ‘Solitude is one of the devil’s scenes’, John Donne, poet and Dean of St Pauls Cathedral, sermonised on Easter day 1630.

Seven years earlier Donne wrote about unwanted solitude in words that have special resonance for us today, as we self-isolate to protect ourselves from Covid 19. Of course many of us are not living alone but in households, sometimes very crowded ones, as we long for healthier times to return. But aloneness is the fate of many. In an article posted on History Workshop Online this month, David Vincent and I discussed the impact of this solitariness. Our article begins with Donne’s cri de coeur from his lone sickroom:

As Sickness is the greatest misery, so the greatest misery of sickness is solitude; when the infectiousness of the disease deters them who should assist, from coming…Solitude is a torment which is not threatened in hell itself.

The rest of our article is available to read here.

[1] Euan Roger, ‘Living with Leprosy in Late Medieval England’, National Archives blog, 5th November 2019.

Barbara Taylor is Professor of Humanities at Queen Mary University of London and Principal Investigator on the ‘Pathologies of Solitude’ project.