Barbara Taylor

When I was awarded the Wellcome Trust grant for this project I had ideas about the type of people with whom I would like to work, but never could I have imagined the wonderful team with whom it’s been my pleasure to collaborate over these last four years.

The appointment of Clare Whitehead as project manager gave us leadership that has been brilliantly efficient and wonderfully empathic. It was Clare who held the project together as it passed through some difficult times, most notably during the pandemic. She and I then went on to recruit Akshi, James and Charlie. In the final year of the project Tasha joined us.

What have we become to each other? Co-workers, friends: but also, I want to suggest, part of our inner lives, the realm of fantasy that we experience most powerfully when alone.

During the project I began to dream about members of my team. I felt myself drawn to them, as they are, but also to images of them. They are very different people although with much in common: personal warmth, generosity, a great sense of humour. I like to flatter myself that I share in these qualities, but over time I learned so much from them!

Sometimes the learning curve was steep. This was particularly the case with regard to issues of race and ethnicity where Akshi Singh took the lead and in doing so transformed our project. Her work, along with Nisha Ramayya and Tasha Pick, has resulted in some of the most exciting outcomes from the project, as is readily apparent from our website.

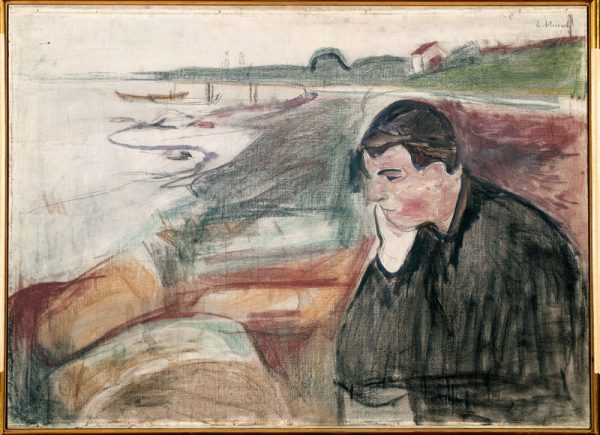

I am a historian of subjectivities. It’s long been my belief that understanding solitude is key to our understanding of human subjectivity. Solitude is not a unitary experience but a fantasy scenario, an imaginary staging of self that is far too complex, too psychically dense, to be captured by any simple opposition between absence and presence. Historians have been reluctant to tangle with this complex psychological state but history, I believe, offers us many insights. My own research is an investigation into this: into the long history of solitude as a story of what Aristotle dubbed phantasmata, the figures that appear in our dreams, but also – I argue – in our waking lives as fantasies of others, the unconscious inner presences that compose us.

Psychoanalysis offers many insights into these presences, but it has its limits. Literature, especially poetry (as James Morland shows) can be a rich source of imagery of solitariness that reach deep into people’s psychic lives, especially during experiences of bereavement and grief. Recent years, with the Covid 19 pandemic, have made such experiences all too common, especially in communities that lack the resources to deal with a major health crisis.

The enforced solitude of the pandemic pushed our project online. The meetings we had held in our ‘Solitude’ office at QM – with its delicious baked goods from James and Indian sweets from Akshi – abruptly came to an end. I found this extremely painful. These meetings had, for me, been joyful occasions (as were our informal meetings in each others’ homes). Suddenly my team went digital. The sense of loss was enormous. And the sense of loneliness that attends such loss. Now I really did need to hold my team in my mind, to feel their presence in their physical absence. Zoom was better than nothing but no substitute.

In this final blog I want to warmly thank all my team for the happiness they have brought me. I am sure we will keep in touch, but it will be different. I am so glad to have worked with them and to know that they will remain a part of me, both consciously and unconsciously, as we move our separate ways.

James Morland

Through the course of this project my research has become focused on the dualities of solitude in the eighteenth century. While the fact that solitude has positive and negative ramifications might seem a fairly obvious point, the way that these are expressed can give a nuanced history of how solitude has been seen and experienced. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, solitude was often a condition that enabled contemplation, but with that came severe risks. Solitude was a productive and perilous place to be. A moment of peaceful retirement in a shaded grove that brought a deeper connection with oneself or the divine, could also quickly turn sour if the mind turned to ‘sickly musings’.

A late eighteenth-century example of this can be found in the English translations of Johann Georg Zimmermann’s Solitude Considered with Respect to its Dangerous Influence Upon the Mind and Heart. Zimmermann argued for a balance between the ‘comforts and blessings of society’ and the ‘advantages of Seclusion’, with chapters attempting to balance the positive and negative effects of solitude. In the 1799 translation of Zimmerman’s treatise, a quotation from an English physician-poet, John Armstrong, appears at the opening of the chapter on ‘The Disadvantages of Solitude’, providing a poetic explication of the view of solitude ‘allowing a weak and wicked mind leisure to brood over its own suggestions [that] recreates and readers the mischief it was intended to prevent’:

Chiefly where Solitude, sad nurse of Care,

To sickly musing gives the pensive mind.

There Madness enters; and the dim-eyed Fiend,

Sour Melancholy, night and day provokes

Her own eternal wound. [Preserving, IV.90-4]

Armstrong’s lines are used to depict what Zimmerman depicts as solitude ‘keeping the mind free to brood over its rank and noxious conceptions, [becoming] the midwife and nurse of its unnatural monstrous suggestions’. Solitude’s status as a midwife of its own ‘unnatural monstrous suggestions’ is key to understanding the duality of solitude across the century. Solitude’s withdrawal had a specifically curative and nourishing quality, hence its close association with the imagery of nursing, but simultaneously could allow a weakened mind to brood and foster its own melancholy habits.

But these dual aspects of solitude were not just confined to the eighteenth century and the continued questioning of the duality of solitude through history has been apparent throughout many of the conversations I’ve had with members of our research network. I’m so grateful to the network for enriching the ways I have thought about the history of solitude. Some of these connections have come through in the blogs published on our website.

Hetta Howes gave an insight into the conversely sociable solitude of the enclosed spaces of medieval anchoresses, where solitude ‘in its most perfect form [ends] up being full of sociable heavenly chatter’, itself a significant trope in eighteenth-century poetry where solitude allowed a deep connection with the divine. Nick Jones took us on a journey through outer space and notes that in these contemporary films while space ‘may have the potential to be overwhelmingly lonely, [this] serves not as an opportunity to sever all human bonds but a chance to remind ourselves of their importance’, a point made by Mark Akenside, a mid-eighteenth century physician who argued that the a pensive ‘absent hour’ can remind one of the ‘sober joys of friendship’. Charlie Williams reflected on the rare pleasure of having the house to oneself in lockdown where ‘such moments are most enjoyable when they are the counterpoint to a busy and hectic life’, echoing Zimmerman’s balance between the ‘comforts and blessings of society’ and the ‘advantages of Seclusion’.

During the UK’s first period of COVID lockdowns, we began to form an archive of written testimonies about how the pandemic had changed people’s experiences of solitude. The responses often mirrored the dualities of solitude that I had been researching in eighteenth-century poetry. While for some the perils of solitude were evidently clear, there were also many pleasures to be found in the solitariness of lockdown. If for one person, a pandemic solitude ‘seems like the worst thing in the world’ for another the ‘forced solitude has given me time […] to re-evaluate what and who is important to us’. Solitude and contemplation have long been intimately linked, and these responses have echoes of the discussions between eighteenth-century poets and philosophers questioning what it means to ‘Know thyself’ in solitude.

While these accounts may not use the same language and diagnostics of ‘sickly musings’ or ‘sour melancholy’, there is a distinct similarity between these eighteenth and twenty-first century accounts of solitude. Solitude has historically been a difficult experience to explain, but its oppositional qualities have been central to attempts to define it.

A final thank you to the wonderful Solitudes team, who have become close friends and made time on this project a joy. They have been inspiring colleagues and have also been steadfast supports through difficult personal moments during the course of this project.

Charlie Williams

I have spent the past three years writing and thinking about the figure of the dropout in Britain and America during the early Cold War. Prior to this, ‘dropout’ had been either an administrative or derogatory term used to refer to university or school leavers, but in the 1950s and 60s it acquired far more loaded meaning; as a form of protest, a rejection of institutionalised life, experimentation with drugs and lifestyle, a symbolic identification with outsiders of various stripes, and often touted as a form of internal liberation or the start of a psychic journey. Though not all the counterculturalists that embraced the term dropout were solitaries (some actively rejected solitariness), much of the discourse on dropping out drew upon the long history of solitude. In our three years on the Solitudes Project it has been a privilege to work alongside our extensive research network and explore how themes of mental health, internal liberation, imprisonment, inner-dialogue, privacy, religiosity, individualism and sociality have percolated throughout the long history of intellectual thought on solitude. My research focuses on the way that the post war dropout reprised these themes amidst concerns about the growth of the human sciences and fears of so called ‘brainwashing.’ I’m incredibly grateful to all of those who participated in our seminars, colloquia and exhibitions, and those wrote blogs and contributed to podcasts for what they brought to the project and the way they have sharpened my thinking about the dropout.

Coming to the end of the project is also an opportunity to think about the past 3-4 years which, it goes without saying, have been unexpectedly turbulent times. For our team, the pandemic not only required us to change our way of work, but also to channel our focus into thinking about solitude and loneliness in the here and now. The testimonies we heard and discussions we had demonstrated the vast variety of lockdown experiences, too often felt unequally across society, which included overlapping feelings of loneliness, solitude as well as crowdedness and lack of solitude. The subtitle of my book, ‘the politics of disconnect’, refers to the 1960s interest in minds disconnected from mainstream culture, but it also speaks to contemporary discussions about the digital age. I suggest that in the last decade the utopian ethos that accompanied the arrival of the early internet has waned. Many of those same technologies that were once seen as connecting, creative and democratic have come to be seen as addictive, invasive and manipulating. But during the pandemic, many of us relied on our interconnected devices more than ever to mediate our social interactions. During one discussion, our colleague David Vincent pointed at that in many ways this moment revived that early vision of the internet as a tool of inventive sociality. As our research on solitude continues and merges with future projects, I am sure the conditions of the pandemic will remain an important touchstone in discussions about the role of technology in our solitary and social lives.

And finally, a massive thank you to the wonderful project team. Akshi, Clare, James and Tasha have been inspiring colleagues and cherished friends and I look forward to continuing our regular hangouts as we embark on our different journeys. On behalf of all of us, the last dedication goes to our fantastic project leader Barbara Taylor, who led the project with enduring curiosity, intellectual rigour and abundant warmth. We will miss her mentorship (generously supplemented with tea and biscuits) and the many great times we spent together hugely.