My lockdown fantasy? I don’t have one. I hanker after restaurants, the cinema, holidays, I yearn for family and friends. I rage at our government, and I panic over my computer. But I don’t dream about food, or wine. I don’t have fantasies about sex, and haven’t since Elvis sang ‘Wooden Heart’ to Juliet Prowse in G.I. Blues and I was there, I was her. I made an exception for Regé-Jean Page, though I’m old enough to be his grandmother, but nothing that a nip and a tuck and a bit of lipo-suction wouldn’t put right.

But otherwise? No.

And yes. Because my life in lockdown is one, long fantasy. I spend my days inventing stories, peopling my world with characters and conversations, landscapes and situations. I live in the heads of my protagonists, imagining their reactions and responses, drawing out dialogue, refining and polishing it so it appears natural and authentic.

I send them out and about, tracking their steps on Google maps, describing their homes from Google street view. I send them abroad, and back in time, browsing Alamo and Getty as I write my word pictures. I dress my people up and I dress them down, I check my vocabulary so there is no hint of a period lapse, I invent names common at the time, I browse back-copies of the Radio Times to check what they were listening to. I weep with them, and for them. And at the end of the working day, I think, this isn’t so bad, this is what I do every day anyway. Lockdown fantasies? Lockdown diary more like.

Now, here’s the thing. In the first lockdown I completed a novel I’d begun a couple of months earlier. It took me a while to adjust, to the knowledge that there was a pandemic raging in the world even though the view from my windows looked no different, to establish a fresh equilibrium where cinemas and restaurants and friends and family were out of bounds, where we were risking life and limb to go to the supermarket, to adjust to the hourly airdrops of memes and jokes and emails which filled my inbox. This, I imagined, was what house arrest must be like. In common with everyone else, I discovered Zoom, Bluejeans and Teams and other video conferencing platforms.

My diary filled up with a virtual life, no substitute, we all said, for the real thing, but isn’t it wonderful? Family zooms around the world, cocktails with friends. We dropped into a Boxing Day drinks party in New York, had a workshop with a colleague in Calgary, I was interviewed by the Court Theatre in Chicago. It was all new, innovative and different. I didn’t feel threatened by COVID, nor did I fear it. No one I knew had it. I pressed the refresh button every day and carried on as normal, delivering my novel to my publisher months before the deadline, ready to enjoy the summer’s heat, the relaxing of restrictions, our new granddaughter.

And another novel, begun in lockdown #2. The opening of a new project is always exciting, like starting an affair, the buzz of the meeting, the flush of desire, the excitement of discovery, the joy in the getting-to-know-you stage. A fresh fantasy. This one has at its heart a family secret, memories buried so deep they had become lived lies. Memory in lockdown.

I’m experienced enough now to know that I hit a wall at about 20,000 words, and getting over that wall involves a hard slog. Writing isn’t all fun, the thrill of the chase. It’s a question of perseverance and critical distance. Is this story working? This time, the wall coincided with Christmas. Time off, time out, even though we could go nowhere, much less see, hug, kiss any loved ones.

And into lockdown #3. The wall had been surmounted, and the writing continued. But my mood was different. Flat, deflated, resigned. This time, the virus raged very close indeed. Two of my three daughters, and their families, contracted it. They’re young and fit and recovered. But other friends caught it. Two sadly died from it. We could grieve but not mourn, not together, collectively, a shared catharsis. Sometimes I think I glimpse my dead friends, but it is a trick, a fantasy of loss. Other, dear friends suffered for weeks, months and perhaps longer, pain and fatigue, headaches and rashes. Gone are the memes and jokes and the torrents of messages. There is nothing new and innovative now, just a dreary grind of a life closed in, mundane, locked down, dead.

Lockdown novel #1 crossed a rough, imaginary terrain, up and down, in and out. It ran along blind alleys and snaked through mazes, a zig-zag of a story with its highs and lows, the stories of lives lived in time. Lockdown novel #2 was as flat as the mood around me, as level as the fens in which it is partially set. I drew a dull and uninspired word-scape. My fantasy world was a reflection of the real world in which it was being invented, with none of the kinks and twists, the surprises and rotations, of a plot well drawn, a story dazzled.

My editor sensed it, the inevitability of the story, its predictability. I was treading water, my writing performative, the plot becalmed. My imagination had gone into lockdown, my fantasies flattened, my energy perfunctory. Who knew that a writer was sensitive to their surroundings? ‘In your working conditions avoid everyday mediocrity,’ wrote Walter Benjamin in One-Way Street, ‘Semi-relaxation, to a background of insipid sounds, is degrading.’ [i]

Ever the melancholic, for Benjamin death sharpened meaning, or at least correlated with it. ‘The amount of meaning is in exact proportion to the presence of death and the power of decay.’ [ii] I haven’t extracted meaning from the death that now surrounds us. I haven’t wanted to write about the pandemic. I have nothing to say. It needs time, to filter into the mind, for the mind to sift the meaningful from the peripheral, for the peripheral to become meaningful too. It needs time to meander, to get lost, just as death takes time to absorb. There is the initial shock, of course, followed by the pain, the anger, the depression, that steamroller that skews the map reading of the soul so the hills become mountains, the valleys chasms and the horizons mirages distorted in the haze.

And then there is resignation and mediocrity.

My editor, ever the professional, suggested a route out. What if, she said, the family secret is a fantasy, for there is another secret, layered on, or rather, beneath the first? A memory locked down, within another. That the secret is not a single artefact to be excavated, but sediment to be scraped away, revealing the layers of a family detritus, the bones, the excrement, the pottery shards. An imaginary midden.

And thus was born my true lockdown fantasy, a landfill of ideas and words, memories and experiences in which to rummage and dig, clean up and re-use, marvel at or discard. As for lockdown novel #2 – my fantasy has begun to run past the flattened, mediocre landscape towards a more familiar one, glimpsed like a loved one in the distance. It has begun to run and skip, jumping over the tussocks of a rising fictional moorland, skinny dipping in a cold mountain lake, reaching for a future beyond lockdown. And, lurking in the background, perhaps, the germ of an idea for the next novel, set in a confinement of a different time and place, teasing at the compromises needed to escape…

[i] Walter Benjamin, ‘Post No Bills’ in One-Way Street, London, Verso, 1979, p.65

[ii] Cited by Susan Sontag, in ‘Introduction’ One-Way Street, p 21.

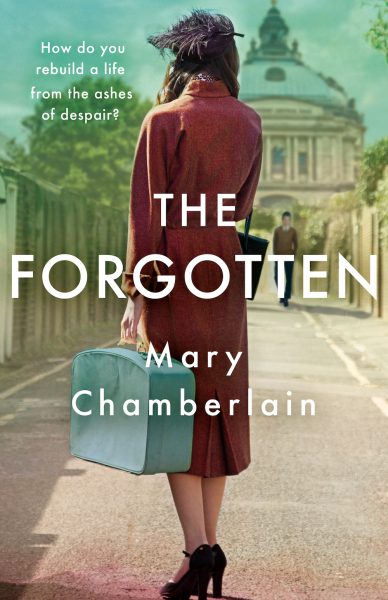

Mary Chamberlain (@MaryChamberla12) is an author and historian. Her third novel – The Forgotten – is forthcoming in September 2021.