In the solitary depths of lockdown earlier this year, we began organising a conference on the experience of loneliness in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Our interests were twofold: what could the historical record tell us about loneliness, solitude, and isolation in this period? And how are modern-day academics, particularly those working in the arts and humanities, affected by professional loneliness as a result of precarious employment and the devasting consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic?

‘Loneliness’ as a term in its modern sense emerged in the late eighteenth century; scholarship on loneliness and isolation has therefore tended to overlook the early modern era in favour of later periods on the assumption that people living in earlier times were rarely alone, and that they lacked the necessary emotional vocabulary to acknowledge and respond to feelings of social isolation. Nevertheless, our own research, along with the findings of the participants of our conference, has revealed that early modern people were capable of expressing complex and often contradictory emotions in response to both loneliness and solitude in a wide range of writings.

Historians of emotion might be inclined to distrust literary texts on the basis that they do not represent actual historical occurrences.[i] A subsidiary objective of our conference was to emphasise the value of literary texts as crucial sources for uncovering references to loneliness and solitude. Our blogpost therefore investigates a specific facet of solitude in two genres of early modern literature: the meditation and the sermon. We argue that loneliness arising from widowhood and remarriage affected the lives and writings of our chosen authors, and that their opinions on seeking solitude were fraught with ambiguity.

I Cant but recite to my selfe my former sweetnes of life […] but that his love to his relative may not be of a far more excellent nature and effect to me then before […] Tis problematical […] Tho some providences and marks have gave me some demonstrations

(f. 23r / p. 69).

Austen chooses not to remarry out of love for Thomas, noting: ‘For my part I doe noe Injury to none by not Loveing’. More candidly, she writes: ‘As for my body it can be enjoyed but by one’ (f. 95v / p. 147). Writing of her affection for another male friend, with whom she had an obvious intellectual connection, she remains stoic in her decision to stay true to Thomas: ‘I declined all things might give him a vaine encouradgement. and told him I was like pennelope, alwayes employed’ (f. 96r / p. 148). Despite physical solitude, Austen found solace in her husband’s legacy.

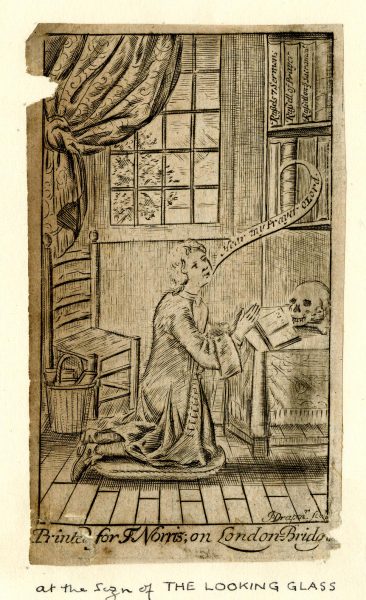

In contrast, Austen’s contemporary, Elizabeth Delaval (1648?–1717), had a far unhappier experience of marriage, which is delineated in her Meditations. Delaval accrued immense debts during her time at court, desiring retirement as a means to shield herself from further corruption: ‘Who ever think’s most certenly must prize / A life retier’d, and croud’s and noise dispise’ (p. 120).[iii] While in retirement, Delaval confesses that the single life is how she would ‘chuse to lead all [her] day’s’ (p. 90). When marriage is proposed as a means to pay off her debts, Delaval is strongly opposed on the grounds that the marriage would make her beholden to her husband’s family, stating, ‘[I] do firmely resolve never to be maryed at all, rather then to mary whilest I am in debt […] no one friend I have finds it reasonable to argu this poynt’ (p. 90). Delaval was alone in her position. Her response to her marriage was to increase her time in solitary devotion: ‘I will now begin to rise so early every morning, that I may be at least too houers alone in my closet’ (p. 208). Ultimately, her solitude within her closet served as a protest against this symptom of a society which denied women financial freedoms and marital choice.

The meditations of Austen and Delaval constitute a series of prose entries, prayers, verses, and transcriptions. One of the most fascinating characteristics about early modern English literature is the fluidity between textual genres; a sermon, which started out its life as an oration delivered at the pulpit, could be transformed into a treatise or meditation in its printed form.

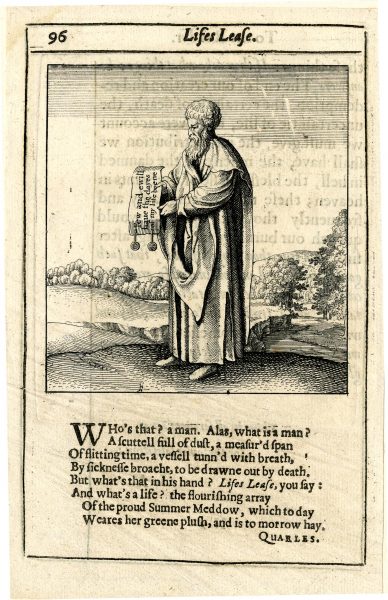

Thomas Gataker (1574–1654), rector of Rotherhithe, published a considerable number of sermons during his lifetime which gained new leases of life as extended meditations on biblical texts. Although these texts were considerably more public than the meditations of Austen and Delaval, read within the context of his own life, they reveal much about his perspectives on solitude and companionship. The Spiritvall Watch, or Christs Generall Watch-Word (London, 1619), is a ‘meditation’ on Mark 13:37 (‘And what I say unto you I say unto all, Watch’). Highlighting the importance of vigilance, Gataker expounds the perils of being alone:

it is dangerous for vs in regard of our drowsie disposition to be solitary; we may the sooner be surprised with sinfull suggestions, the more easily be drawne to yeeld to Satanticall temptations

(p. 49).

Copiously peppered with citations from the Bible, classical sources, and the works of contemporary divines, The Spiritvall Watch is a scholarly contemplation of the ways in which being alone made a Christian vulnerable to ‘Satans assaults’ (p. 52). Gataker presents further arguments against solitude in a printed marriage sermon. Citing Ecclesiastes 4:11, he argues that

Solitude is vncomfortable: There is no warmth in it.

Moreover, husband and wife constitute ‘the maine Root, Source and Originall of all other Societies’.[iv] Certainly, these views were consistent with Gataker’s private life. In his funeral sermon for Gataker, fellow London preacher Simeon Ashe described the Protestant divine’s years of ‘disconsolate solitude’, having been widowed twice in the space of two years.[v] Although Gataker had been in ‘constant retirement in his study’, Ashe emphasised his commitment to love and companionship which was extended towards his stepchildren.[vi] Withdrawing to his study was necessary for Gataker, but he did not desire to be in a permanent state of solitude.

Our blogpost has revealed that, while a duty to religion governed the attitudes of early modern widows and widowers towards solitude, their personal feelings in response to bereavement and (re)marriage, enforced or otherwise, were articulated in their writings, both private and public. Katherine Austen, Elizabeth Delaval, and Thomas Gataker may not have used the word ‘lonely’ but, for differing reasons, all experienced a sense of emotional isolation as a result of their solitudes.

[i] Kristine Steenbergh and Katherine Ibbett, ‘Introduction’, in Compassion in Early Modern Literature and Culture: Feeling and Practice, ed. by Kristine Steenbergh and Katherine Ibbett (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), pp. 1–21 (p. 13).

[ii] Sarah C. E. Ross, ed., Katherine Austen’s Book M: British Library, Additional Manuscript 4454 (Tempe, AZ: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2011).

[iii] Douglas G. Greene, ed., The Meditations of Lady Elizabeth Delaval (Gateshead: Surtees Society, 1978).

[iv] Thomas Gataker, A Wife in Deed, in Thomas Gataker, A Good Wife Gods Gift: And, A Wife Indeed (London, 1623), pp. 28–29.

[v] Simeon Ashe, Gray Hayres Crowned with Grace (London, 1655), p. 50.

[vi] Ashe, Gray Hayres Crowned with Grace, p. 49.

[vii] Roland Walls, From Loneliness to Solitude (Oxford: SLG Press, 1976), p. 2.

Hannah Yip (@EMLoneliness) is a UK Research Assistant for ‘GEMMS – Gateway to Early Modern Manuscript Sermons’ (SSHRC / University of Saskatchewan, Canada).

Thomas Clifton (@ThomasCliftonA5) is an AHRC-funded PhD Candidate in English Literature at the University of Birmingham.