With their parallel lives, animals offer man a companionship which is different from any offered by human exchange. Different because it is a companionship offered to the loneliness of man as a species.

John Berger, ‘Why Look at Animals?’ (1980).

Any exploration of John Clare’s life and work in relation to solitude cannot ignore his most profound experiences of being ‘shut up’, as he described it, away from others.[1] The poet spent the final portion of his life in asylums, after living with increasingly frequent mental, physical, and emotional disturbances that some have considered a form of bi-polar, some have likened more to schizophrenia, some have credited to the strains of poverty and malnourishment, and that Clare called simply his ‘indisposition’. A patient at High Beach Asylum in Epping Forest from 1837-41, Clare’s escape from Matthew Allen’s institution is captured in his prose account ‘Journey out of Essex’. Following an apparent delusion of being reunited with Mary Joyce, a childhood sweetheart whom Clare believed to be one of his two wives (the other being his actual wife, Martha ‘Patty’ Turner), the poet walked from Essex to Northborough only to find Mary Joyce long dead and himself ‘homeless at home’ when he got there.[2] Later that same year, Clare was committed to Northampton General Lunatic Asylum where he remained until his death in 1864. For the purposes of historical accuracy and, perhaps, to rescue Clare from his sentimentalised Victorian reception as a dishevelled, mad genius being led away against his will,[3] more recent biographers and critics are frequently keen to stress that Clare’s initial admission to High Beach was ‘voluntary’.[4] Clare’s own written accounts, however, speak of the suffering and resistance endured under an ostensibly ‘voluntary’ admission. In April 1841 Clare wrote to his wife, Patty, from High Beach, that ‘I am still here […] enduring all the miseries of solitude’; in May that same year, he drafted a letter to his imagined wife, Mary Joyce, lamenting ‘how sick I am of this confinement […] if I was in prison for felony I could not be served worse then I am’.[5]

Clearly, there are important tensions to bear in mind regarding ‘voluntary’ as a legalistic term used to confirm free will or choice, and its association with more purely volitional actions, thoughts, or feelings not born of compliance.[6] Clare’s ‘voluntary’ admission to High Beach, if not forced, was certainly not a free individual choice, but more the result of collective negotiations between domestic and medical authorities. Akihito Suzuki’s study of ‘madness at home’ in the nineteenth century is alert to how ‘the “voluntary” committal of lunatics gave the family another means to resolve domestic discord by mobilizing public authorities’ intervention’.[7] The result of discussions between Clare’s publisher John Taylor and the asylum’s owner Matthew Allen, the poet’s admission to High Beach was eventually agreed on ‘the authority of his wife’, as Jonathan Bate has it.[8]

Yet although the asylum was often a place of profound loneliness and confinement for Clare, where solitude can never be truly exercised as a free choice, it was also a space from which he looked back on past solitudes, and from where he made some of his most profound statements about solitary pleasures. Writing to his son, Charles, in 1848 from Northampton General with some fatherly advice in lieu of his absence from family life, Clare advised that Charles take up ‘angling’ for its solitary, boyish charms:

Angling is a Recreation I was fond of myself & there is no harm in it if your taste is the same – for in those things I have often broke the Sabbath when a boy & perhaps it was better then keeping it in the village hearing Scandal & learning tipplers frothy conversation […] in my boyhood Solitude was the most talkative vision I met with Birds bees trees flowers all talked to me incessantly louder then the busy hum of men’.[9]

Clare’s attempt to find some common ground with his son across the distance of separation also leads him to anticipate their differences. His recollection of his own ‘recreations’ takes on the quality of confession, and not only because he describes enjoying breaking the Sabbath to sneak away from the rest of his church-going village. Clare’s sense that his early love of solitude may not be to everyone’s ‘taste’ is charged with an awareness of his own oddity. There are echoes here from the poet’s autobiographical writing, where he recalls being thought strange by local villagers as he went about ‘muttering’ stories to himself inspired by that most compelling study of solitude, Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe: ‘new Crusoes and new Islands of Solitude was continually mutterd over in my Journeys to and from school’.[10] Solitude has a hallucinatory quality in Clare’s letter as a ‘talkative vision’ in sympathy with his own childhood ‘mutterings’. It is never difficult for the poet to find shades of madness in childhood pursuits. His poem ‘Emmonsales Heath’, for instance, recalls the ‘joyous rapture’ felt searching for ‘pismires’ (ants) as a boy; the young Lubin in ‘The Village Minstrel’ has a similarly rapturous communion with the natural world, where ‘Enthusiasm made his soul to glow / His heart wi wild sensations usd to beat / As nature seemly sung his mutterings did repeat’. Writing from an asylum about hearing the natural world as a voice that ‘talked to me incessantly’, Clare may invite us to hear echoes of pathology in his solitude, but he also reveals it as kindred with the companionable comfort of childhood self-talk. And, alongside any hints of delusion also run conscious choice and volition. Clare’s sensitivity to his own temperament and how it may differ from others is explored along broader lines of human and animal difference, and to be able to hear the incessant talk of ‘Birds bees trees flowers’ above the ‘busy hum of men’ is here to have made a deliberate effort to attend to the nonhuman company that solitude allows him to keep.

Clare’s admiration for Byron’s verse is well known, and it was to Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage that he turned for solace in High Beach, writing his own version ‘to get myself better’.[11] If ‘impersonating’ Byron on and off the page became a form of therapy for Clare in the asylum (rather than the outright delusion earlier critics have made it out to be), then we can also look to Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage as a meditation on the reparative nature of voluntary solitude. Byron’s Childe Harold, who casts himself out to seek a form of ‘society where none intrudes’ (Canto IV, CLXXVIII, l. 3), discovers a ‘populous solitude of bees and birds’ when following the tracks of another outcast—Rousseau—in Switzerland (Canto III, II, l.1). It is the turn away from human to nonhuman ‘society’ that encourages Harold to re-envision solitude as a state ‘where we are least alone’, because we are open to and aware of other forms of being (Canto III, XC, l. 2). The natural world as an alternative form of society away from the corrupting influences of human sociability is a recurrent theme in eighteenth-century reflections on the pleasures of retirement, as well as a Rousseauian form of retreat into the ‘state of nature’. We can hear in Clare’s recollection of his childhood encounters with ‘Birds bees trees flowers’ a form of Byron’s ‘populous solitude’, a tentative bridge between idiosyncrasy and inherited forms; what he sees as a marker of his difference from other boys also has its roots in poetic and philosophical tradition. Bolstered, then, by Byron’s transformation of exile into the pleasures of retreat, Clare is able to find in the ‘Bastille’ of High Beach a form of isolated sanctuary: ‘These solitudes my last delights shall be / The leaf hid forest – & the lonely shore / Seem to my mind like beings that are free’ (‘Child Harold’). What is this freedom found in loneliness? An opportunity, perhaps, to seek out the other forms of company gifted by an environment. Clare’s own fondness for a ‘talkative’ solitude full of animal presence shows him to have inherited what Barbara Taylor describes as the long history of paradoxical rhetoric around what it means to be solitary and the perennial question of ‘who are we with, when we are alone?’[12] One way towards an answer might be to think about those nonhuman beings who, for Clare at least, are a source of consolatory companionship.

‘Emmonsails Heath in Winter’ is a poem from Clare’s ‘middle period’ (spanning roughly 1822-37). With its quick succession of birds that swing and flap into the poet’s view, the sonnet is characteristic of what Seamus Heaney described as Clare’s ability to capture the ‘one-thing-after-anotherness of the world’:[13]

I love to see the old heaths withered brake

Mingle its crimpled leaves with furze and ling

While the old Heron from the lonely lake

Starts slow and flaps his melancholly wing

And oddling crow in idle motions swing

On the half rotten ash trees topmost twig

Beside whose trunk the gipsey makes his bed

Up flies the bouncing wood cock from the brig

Where a black quagmire quakes beneath the tread

The field fare chatters in the whistling thorn

And for the awe round fields and closen rove

And coy bumbarrels twenty in a drove

Flit down the hedgerows in the frozen plain

And hang on little twigs and start again

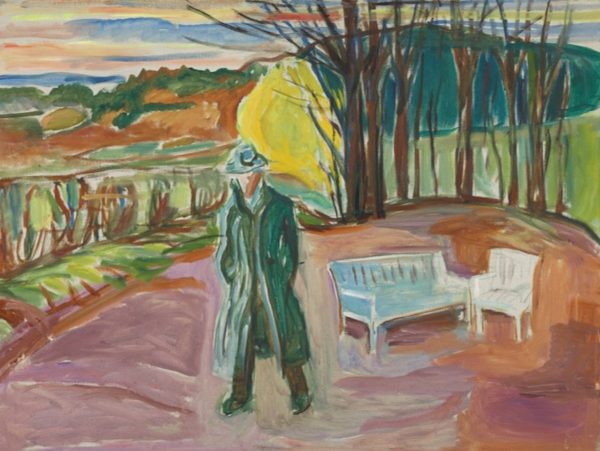

This is not, at first glance, a poem about solitude. There is, apart from the opening first-person ‘I’, a distinct lack of the speaker’ presence or sense of introspection, and more of what Heaney suggested was Clare’s ‘objective clarity’[14]; the speaker is absorbed ostensibly in looking carefully, or lovingly, at things as they are, and as and when they appear, not as projections of his own emotional state. The scene laid out in this sonnet is, I think, expressive of a kind of ‘populous’ (to use Byron’s word) animal sociability that the speaker is happy to stand back and watch. Here, what might usually be thought of as a desolate and barren landscape—a ‘withered’ heath in winter—becomes crowded and busy under Clare’s watchful attention and appreciation. John Berger’s sense of the ‘parallel lives’ of nonhumans and humans is enacted in the poem’s form as much as its content, as its successive lines gather a haphazard company of leaves, birds, lake, trees, a gipsey, a quagmire, fields, hedgerows, and twigs that are held alongside one another and ‘mingle’ in the space of the sonnet.

Yet if Clare’s organisation of the scene fosters a form of mutual coexistence in this poem, it is also highly sensitive to things that stand out. I am drawn here especially to the ‘oddling crow’ that makes its ‘idle’ appearance in the sonnet’s fifth line. A Northamptonshire dialect word, ‘oddling’ refers to ‘one differing from the rest of a family, brood, or litter; generally applied to the smallest or to one with any peculiarity’. [15] As an adjective, however, it also means ‘solitary’.[16] It is a word that, for Clare especially, bridges the gap between human and animal (human and nonhuman families, broods, and litters all have their ‘oddlings’), but also contains a potent reminder of solitude’s inherent oddness as well as its pleasures. Johanne Clare writes of Clare’s frequent depiction of lone animals and birds that he is drawn especially to the ‘aesthetic momentousness’ of solitude, the striking visual image of ‘catching sight of a lone heron circling an empty sky’.[17] Indeed, the word ‘oddling’ recurs frequently in his verse as a means of visual placement. In ‘The Last of Summer’, for example, there are ‘oddling daisies peeping nigh, / Untouched by sheep that hither stray’ (ll. 82-83); in ‘March’ from The Shepherd’s Calendar (1827) Clare describes ‘ground larks on a sweeing clump of rushes / Or on the top twigs of the oddling bushes’ (ll. 85-86) as well as an ‘oddling bee oft patting passing by’ at the window of an ‘old dame’ as she works at her burring wheel’ (ll. 125-131); the ‘The Bumbarrel’s Nest’ opens with ‘The oddling bush’ that the bird has chosen as a ‘sheltered’ (l.1) place to build its nest. All of these ‘oddlings’ have been singled out for the poet’s attention, but their solitary nature comes to be counteracted with plurality or cohabitation. To notice ‘oddling daisies’ and ‘oddling bushes’ is to notice that there is more than one, and to see how ground larks and bumbarrels choose ‘oddling bushes’ for their perches or nests is to see solitude expanded into co-species togetherness. There is comfort for Clare, I think, in these incorporations of ‘oddlings’ into a scene or assemblage, and making them companionable with other beings. If we are attentive to how the word ‘oddling’ holds dual, but profoundly related, meanings of solitary and peculiarity or difference from the group, then we can hear how Clare’s awareness of his own solitary habits—and his sense of how this set him apart from the rest of his community—inflects the lone presence of the nonhuman with his very human sense of alienation and feeling out of place. What he finds in these nonhuman ‘oddlings’ is a companionable means of being solitary together.

To return to ‘Emmonsails Heath in Winter’, then, the ‘oddling crow’ that is both a solitary peculiarity in this scene and an integral part of it helps to uncover the human feelings and experience of solitude to be found in the poem, and to turn attention to the subject who looks upon its populous company. Johanne Clare, in an assessment similar to other critical appraisals of Clare’s representations of animals and the natural world, suggests that the poet’s frequent depictions of solitary animals and birds within landscapes do not function as mere ‘correlatives of his solitude’; rather, he ‘ensures the discrete integrity of both species seen, the perceiver and the object of his perception’.[18] Continually admired for his ecological consciousness, Clare is often considered to be a poet who forgoes self-examination in the presence of the natural world in a manner separate from other Romantic-period poets, and does not corrupt its ‘integrity’ with forms of self-projection or pathetic fallacy. Why, then, is the lake ‘lonely’, and the heron ‘melancholly’? In a poem that appears to make no claims for its subject other than they ‘love to see’ what emerges before them, to describe the nonhuman in terms of solitude’s human affects is to seek subtle affinities and a form of companionship, or even to find in the dedicated close observation of animals another way of thinking about the solitary self as a species apart from its kind. Maureen McLane has argued that to read pathetic fallacy solely as an imposition of human consciousness onto nature is to risk losing sight of its crucial sympathetic potential:

not only is there no way out of sympathetic (or antipathetic) projection, it may be that this is precisely the required medium for an acknowledgement of common life. Or rather, we might say that what’s been called the “pathetic fallacy” registers not so much the human expropriation of the animate, or even the inanimate, world but rather an implicit recognition of and mapping of the interdependence thereof.[19]

Clare, then, does not seek in his solitude an appreciation of the ‘discrete integrity’ of the human and nonhuman, but rather the ‘common life’ that can be built out of feelings of oddity and loneliness. He would write in another sonnet, ‘The Sand Martin’, of how seeing the bird ‘far away from all thy tribe’ instilled ‘a feeling that I cant describe / Of lone seclusion and a hermit joy / To see thee circle round nor go beyond / That lone heath and its melancholly pond’ (ll. 9-14). Although Berger suggests that animals cause us to confront ‘the loneliness of man as a species’, Clare’s restorative ‘hermit joy’ is made possible by the sympathetic projection of pathetic fallacy, where loneliness made animal creates a new species of companionable solitude for this poet who so often felt like an oddling amongst his own kind.

[1] Clare, ‘To James Hipkins’, 8 March 1860, The Letters of John Clare, ed. Mark Storey (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985), 683.

[2] Clare, ‘Journey out of Essex’, in John Clare: Major Works, ed. Eric Robinson and David Powell (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 432-37 (437).

[3] Frederick Martin, John Clare’s first biographer, described the poet’s admission to High Beach as Clare being ‘led away from his wife and children, by two stern-looking men’. The Life of John Clare (London: Macmillan & Co., 1865), 269.

[4] See, for example, Simon Kövesi, John Clare: Nature, Criticism and History (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 143 and Seamus Heaney, ‘John Clare: a bicentenary lecture’, in John Clare in Context, ed. Hugh Haughton, Adam Phillips and Geoffrey Summerfield (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 130-147 (138).

[5] Clare, ‘To Patty Clare’, 18 April 1841, Letters, 645; ‘To Mary Joyce’, May (?) 1841, Letters, 646.

[6] See OED, ‘voluntary’, adj., adv., and n., senses 1-7.

[7] Akihito Suzuki, Madness at Home: The Psychiatrist, The Patient, and The Family in England, 1820-1860 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 9.

[8] Jonathan Bate, John Clare: A Biography (London: Picador, 2004),

[9] Clare, ‘To Charles Clare’, 26 February 1848, Letters, 656.

[10] Clare, By Himself, ed. Eric Robinson and David Powell (Manchester: MidNAG / Carcanet, 1996), 15.

[11] Clare, ‘To Mary Joyce’, May 1841, Letters, 646.

[12] Barbara Taylor, ‘Philosophical Solitude: David Hume Versus Jean-Jacques Rousseau’, History Workshop Journal, 89 (2020), 1-21 (2).

[13] Seamus Heaney, ‘John Clare’, 137.

[14] Heaney, 133.

[15] Anne Elizabeth Baker, Glossary of Northamptonshire Words and Phrases, 2 vols (London, 1854), I, 71.

[16] See ‘Glossary’ in John Clare: Major Works, 513.

[17] Johanne Clare, John Clare and the Bounds of Circumstance (Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1987), 165.

[18] Johanne Clare, Bounds of Circumstance, 173.

[19] Maureen McLane, ‘’Compositionism: Plants, Poetics, Possibilities; or, Two Cheers for Fallacies, Especially Pathetic Ones!’, Representations, 140.1 (2017), 101-120 (104).

Erin Lafford (@ErinLafford) is a Lecturer in English at the University of Oxford.