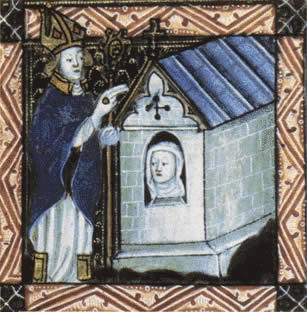

As medieval vocations go, anchoritism must be one of the least palatable to our modern sensibilities. Christian anchorites (male) and anchoresses (female) were solitaries who were permanently enclosed in cells, usually but not always attached to churches, in order to dedicate their life to God. Their existence was imagined as a kind of ‘living death’ – as they were enclosed in their cell, the officiating priest would read the death rites over them, and some of the cells even included a dug-out grave, forcing the inhabitant to meditate continually on their own mortality.

Despite the vocation’s more morbid aspects, anchoritism actually grew in popularity in England throughout the Middle Ages, with numbers rising to 200 in the 13th century as more and more Christians sought an escape from the distraction of everyday life. More than any other religious vocation, this is what anchoritism offered – an escape from the hustle, bustle and temptation of the outside world; an opportunity to focus more wholeheartedly on God. And all of this was made possible by the anchoritic condition of solitude.

The life of a medieval anchorite was characterised by six different but interrelated ideals: enclosure, chastity, orthodoxy, asceticism, contemplative experience – and solitude. In his twelfth-century guidebook for anchoresses, De Institutione Inclusarum, Aelred of Rievaulx outlines two main reasons for choosing this way of life: firstly, to avoid the spiritual perils of the outside world, and secondly, to ‘more freely sigh and sob after the love of Jesus with longing desire’ [1]. Whether the would-be anchorite is looking to escape from the world, or to find more space and time to contemplate on God, physical isolation is a key requirement. Anchorites pursue solitude in order to facilitate a more perfect religious existence.

However Aelred also cautions against the false sense of security that anchoritic living can bring. He writes:

But there are many who do not know the charge nor the profit of solitary living, supposing that it is enough to shut their body between two walls, when not only are their thoughts running about the business of the world, but their tongue is also occupied all day, either by enquiring and seeking after news of the world, or else by gossip [2].

His warning hints at the potential sociability of this ostensibly solitary vocation, and the idea that perfect solitude might be more rhetoric than reality for the medieval anchorite. The three recipients of the thirteenth-century guide book Ancrene Wisse, for example, all lived together, with a number of servants, and were advised to invite those seeking their assistance to stay with them. Aelred himself laments (admittedly with a healthy dose of hyperbole) how rarely even the more isolated anchorites are found alone:

At her window will be seated some garrulous old gossip pouring idle tales into her ears… The recluse all the while is dissolved in laughter… and the poison she drinks with such delight spreads throughout her body [3].

In this striking image, not only the anchoress’ enclosure, but also her body, are permeated, invaded by the dangers of the outside world through the anchorhold’s window. The amount of ink spilled on the potential dangers of this potential sociability, in Aelred’s writing and other anchoritic guidebooks, suggest that it was an inescapable facet of the anchoritic life.

As well as revealing the difficulties of maintaining solitude as an anchorite, Aelred’s warning also reminds his readers that solitude – or at least, the kind of perfect religious solitude which anchorites seek – depends as much upon state of mind as it does on physical environment. It is not enough to enclose the body between the walls of an anchorhold. The anchorite must also work hard to ensure that their mind is enclosed to the world around them – in order that it might become more open to God. Does that mean, then, that religious solitude, which in its perfect form could lead to conversations with the divine, could exists both beyond as well as within the walls of the anchoritic cell? And if so, how might it be constructed? And could it exist without physical enclosure?

A large part of the solitude prescribed by anchoritic guidebooks such as Aelred’s seems to relate to something which, in its most usual form, very much depends on the presence of at least one other person: speech. When Aelred imagines the anchoress socialising with a gossipy old woman, the real danger is the talk she brings with her from the outside world. It drips through the anchoress’s ear to poison and eventually dissolve her body. Silence is imagined as a combative weapon against such dangers, an antidote to spiritually hazardous conversation. If anchoresses ‘dam up their mouths’ then their thoughts will rise up to heaven, instead of spilling out into the world, according to the Ancrene Wisse. Richard Rolle, a fourteenth-century Yorkshire hermit, tells his readers that the less conversation they have, the more joy they will have in God. Throughout these guides there is the sense that in speaking less to other people, there will be more room for speaking with God.

Solitude in the anchoritic life, then, becomes not an end in itself but the means to a much more sociable end. One form of sociability – earthly chatter and gossip – should be exchanged for another, more heavenly brand, through the vehicle of constructed solitude. As one Latin guide puts it: ‘As a solitary, be solitary with the Lord; in reading, hear the Lord speaking with you.’ Anchoritic solitude should not be about fleeing the world but about fleeing the world towards God. The irony of ‘solitude’, as it is conceived and prescribed for the medieval anchorite, is that in its most perfect form it ends up being full of sociable heavenly chatter.

One medieval woman who was certainly aware of the merry sociability of heaven was Margery Kempe. Famous for her loud and boisterous weeping, Kempe was a self-proclaimed holy woman and mystic but not an anchoress (although according to the book about her life and visions which she dictated, one infuriated monk wished she was enclosed in a house of stone, so that she wouldn’t be able to talk to anyone). However, Kempe’s insistence on remaining part of the outside world did not prevent her from enjoying many conversations with the divine. Her book records countless visions in which she speaks with God, Jesus, Mary, John and a myriad of other Christian celebrities.

Many wish silence upon Kempe; whilst travelling to Jerusalem on pilgrimage her companions force her to sit at the end of the table on a little stool, because she refuses to talk about anything other than God, and some even want to throw her overboard to shut her up. However, their efforts are to no avail. She stubbornly continues to talk about heaven and to roar and weep as noisily as ever when she imagines Christ’s pain during his torture and crucifixion. And as she does so, her conversations with God and the heavenly host only increase in number and intensity.

It seems, then, that Kempe’s way of life is in stark opposition to the solitude of anchoritism. She’s out and about in the world, travelling overseas and refusing the silence and solitude which most anchoritic guides prescribe. And yet, if perfect religious solitude can be conceived of as a state of mind – augmented by but, crucially, not dependent upon physical solitude, as Aelred of Rievaulx seems to suggest – then perhaps Kempe deserves another more consideration in this context. By isolating herself from society to the point where those around her wished she was enclosed and out of their way, and by speaking only of God and holy things, Kempe creates a kind of religious solitude out in the busy world. And the results of this constructed social isolation are the same as those of anchoritic solitude: conversations with the divine.

Kempe may have eschewed the ‘living death’ of the anchorhold but in speaking and thinking only of holy things she managed to construct a surprisingly similar form of religious solitude. In closing her ears to the chatter and gossip of everyday life Kempe managed to find an escape from worldly distraction beyond the walls of the anchorhold – and to open them more fully to the word of God, and the merry speech of heaven.

[1] Aelred of Rievaulx’s ‘De Institutione Inclusarum’: Two English Versions, ed. John Ayto and Alexandra Barratt, EETS, O.S. 287 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984), p. 1, my translation.

[2] ibid., p. 1, my translation.

[3] ibid., p. 2, my translation.

Hetta Howes (@HettaHowes) is Lecturer in Medieval and Early Modern Literature at City University London. Her BBC Free Thinking Essay on Margery Kempe and the medieval connection between women and water can be found here.