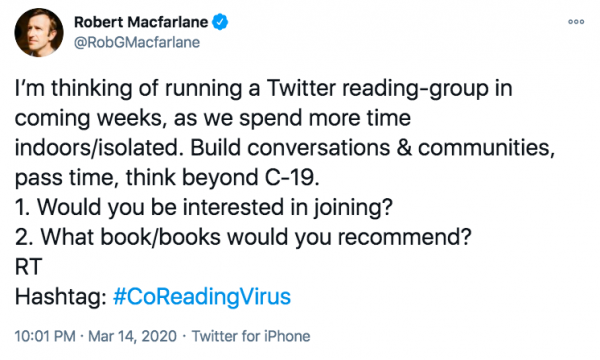

As soon as lockdown was imminent in March last year, Robert Macfarlane tweeted a question:

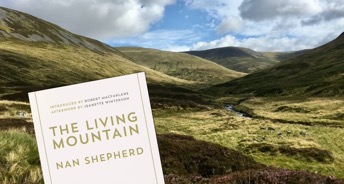

In his 2015 article ‘Why we need nature writing’ Macfarlane describes us, in modern-day Britain, as ‘living through a golden age of literature that explores relations between selfhood, landscape and ethics’.[i] But The Living Mountain would take us back to another global crisis – the trauma of the post-war years – to feel our way through the COVID pandemic and the isolation it brought. During that first period of lockdown and enforced solitude, Macfarlane described Shepherd’s book as a much-needed touchstone, saying that he would love reading it with all of us:

During lockdown, it became imperative that I took my daily exercise in nature, even though the roads often still offered solitude. In The Life of Solitude, Petrarch reminds us that, ‘Woods, fields and streams are of great advantage to the solitary.’[ii] I have often wondered why, and I feel that Shepherd in The Living Mountain gives us some answers to the question, ‘Why does nature sweeten and enhance solitude?’

Firstly, it reinforced for me the need to be ‘heard’ in one’s solitude. Members of the Twitter reading-group shared their travels, walks, reflections on the book and photographs of rock, birds, deer, flowers, lichen and weather.

In our solitude at home, we began to connect and communicate with others and experience a shared calm from remembering places that we walk, have walked and love walking, whilst learning something new from others, including the author herself.

Shepherd articulates this in her thinking about why she feels lighter when walking the mountain:

What more there is lies within the mountain. Something moves between me and it. Place and a mind may interpenetrate till the nature of both is altered. I cannot tell what this movement is except by recounting it (p. 8).

One reader, returning home from their hour’s exercise, was suddenly struck by the fact that they did not know their own front garden, that there was a whole fresh palimpsest of natural experience to be gained right there. Another reader, @LauraSteckley, commented:

There is no concern from Shepherd that this walking must be done alone and we recall that Petrarch avoided crowds, not friends. The friend though, Shepherd notes, must be the right sort of friend:

The presence of another person does not detract from, but enhances, the silence, if the other person is the right sort of hill companion […] one whose identity is for the time being merged in that of the mountains, as you feel your own to be (p. 14).

These companions need not be physically or temporally with us either.

In her walk in ‘Frost and Snow’ Shepherd notices animal tracks and details them as they too pierce the snow, perhaps confidently, or in a deeper covering with difficulty. The brush of a fox is traced across the surface; a single hole with a small patter of tracks shows that a mouse has come up from the ground below and, having looked around, returned beneath:

These tracks give to winter hill walking a distinctive pleasure. One is companioned, though not in time (p. 30).

It is this unimportance of real time that so many readers noticed in the book. Shepherd describes how she became part of the landscape and that this interconnectedness (as @Sarahchave1 observed), ‘changes our ethical relationship’ with place and the environment. Shepherd begins to understand why Buddhist pilgrims walk mountains; she feels that the journey becomes part of the search for the god, a journey inwards as well as a journey on the outside:

For an hour I am beyond desire. It is not ecstasy, that leap out of the self that makes man like a god. I am not out of myself, but in myself. I am To know Being, this is the final grace accorded from the mountain (p. 108).

In his introduction to her book, Macfarlane observes that Shepherd knows what it is to go out to go in, as she describes above at the end of The Living Mountain. He reminds us that it was John Muir, the naturalist and writer, forty years before Shepherd, who first acknowledged in publication:

I only went out for a walk and finally concluded to stay out till sundown, for going out, I found, was really going in.[iii]

Recently, hearing the work of Jason Allen-Paisant, I was struck by a nature-writer’s attention to time. Shepherd walks with all-time and the ancient making of the mountains, but also with the changing of the seasons and what each time brings to the landscape. However, almost more importantly, in considering the smallest of details, she becomes part of the environment and time loses relevance.

Allen-Paisant, writing of his memories of nature as a child in Jamaica, works through a new way of being in nature, knowing that his parents and grandparents needed trees and the earth for growing food, making fires and earning money, but years later in England, he is entranced by trees in blossom in a park. He wants to bear witness to his past, but also to decolonise nature, so that he can respond to it independently:

Now I’m practising a different way

of being with the woods only

I try not to stray too far from the path…[iv]

In this poem ‘Walking with the Word ‘Tree”, he is attracted to the pink pistils of the flowers on a tree that seem to speak out to him, acknowledging his interest:

I don’t even know

what they call it

but I want to know

what it tells me

about itselfits appearance

with thousands of others

on this tree

that up to April

seemed like death.[v]

It is this element of solitude that becomes so strong in nature, that the earth, that nature, that Nan Shepherd’s mountain makes us feel so profoundly: we are part of this huge and, at the same moment, minute ecology. Shepherd articulates it here:

It is therefore when the body is keyed to its highest potential and controlled to a profound harmony deepening into something that resembles trance, that I discover most nearly what it is to be. I have walked out of the body and into the mountain. I am a manifestation of its total life, as is the starry saxifrage or the white-winged ptarmigan (p. 106).

Shepherd does not want to conquer the mountain and look down from its peak to feel the power of a god. Instead she walks amongst it; she becomes familiar with it and, in her solitude, she becomes part of it. This book contains some of the finest nature writing in its poetic, lyrical description; its inclusivity which draws the reader into the environment; and its powerful, but modest and sensitive philosophy. In difficult times during the global pandemic, I found solace and a life-enhancing solitude as I walked, with others, Nan Shepherd’s living mountain.

[i] Robert Macfarlane, ‘Why we need nature writing’, New Statesman, 2 September 2015

[ii] Petrarch, The Life of Solitude, p. 157

[iii] John Muir, John of the Mountains: The Unpublished Journals of John Muir

[iv] Jason Allen-Paisant, ‘Walking with the Word ‘Tree”, PN Review 249: 46 (2019).

[v] Allen-Paisant, ‘Walking with the Word ‘Tree”

Di Beddow (@DiBeddow) is a PhD student at Queen Mary University London. Her thesis is on the Cambridge of Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes.