Self-isolation, social distancing, quarantine – solitude and its protocols have become part of our everyday consciousness and language. Of course, the solitudes of COVID-19 are not strictly voluntary. We none of us chose to be confined to our homes, separated from our colleagues and friends and the world at large. But we may nonetheless have felt some blurring during these months of the line separating voluntary from involuntary solitude.

Public commentary and private conversations have been full of observations and reflections and confessions of a strange passage in the experience of lockdown, from a resentful compliance with the enforced separations and isolations imposed on us, to a transformative embrace of their unexpected benefits. My psychoanalytic consulting room has been replete with voices guiltily and gleefully avowing their ambivalence or even horror at the prospect of a return to the workplace and active social life (alongside many, I should add, desperate for the same).

It seems like a good time in this sense to read Emily Dickinson (though there is never a bad one). Dickinson seems to me to alert us to the ambiguities lurking in the word ‘voluntary’. The voluntary is an assertion of voluntas, or will, implying a certain internal compulsion. From this perspective, I do not choose solitude from among a range of lifestyle options; rather, I’m possessed by the conviction there’s no other way I can live.

Every path out of solitude seemed to Dickinson to lead to the same dead end of imaginative restriction and lifeless compliance, that is, into one or other sanctioned expression of nineteenth-century womanhood: marriage, maternity, service to the local community, perhaps even fleeting fame as an author of the kind of sentimental poetry or fiction women were licensed to write and read. Contrary to the sexist mythology that conditioned posthumous accounts of Dickinson’s life, her decision to embrace what she would call ‘that polar privacy’ of a locked room was not the whimsy of an eccentric spinster aunt, but an urgent bid for imaginative survival.

We may remain reluctant to follow her all the way down the same path, but I wonder if Dickinson’s refusal of worldly life isn’t at least a little more intelligible to us now than it might have been three months ago. Perhaps our period of confinement has cast into relief the tacit coercion towards perpetual activity, and the concomitant devaluation of solitude and imaginative life, that governs our lives in the modern West.

***

My recent essay on Dickinson began from her affair, at once passionate and chaste, with the retired Massachusetts Supreme Court judge and state politician Otis Phillips Lord, a lifelong friend of her father Edward. The correspondence is the only unambiguous evidence we have from her life of a love returned and a shared life contemplated.

Lord had been pressing marriage on her until the moment of his death. If she never assented, it wasn’t because she didn’t love him. But the pitch of her ardour begs an unavoidable question: why did they continue to live apart? Why had she fended off the successive proposals not only of marital but of sexual union?

Some measure of an answer can be found in a letter to him of 1878, in which she told him,

Don’t you know you are happiest when I withhold and not confer—dont [sic] you know that No is the wildest word we consign to Language? . . . you ask the divine Crust that would doom the Bread.

Two years later she wrote, ‘It is strange that I miss you at night so much when I was never with you –’.

The ardent suitor, the withholding maid; what makes these letters more than a rehearsal of tired caricatures of gender and sexuality is their unexpected and disconcerting eroticizing of renunciation. ‘No’ expresses sexual wildness rather than morality. Her bed is more torridly charged for his never having been anywhere near it. Permanent separation, prohibition and privation preserve the ‘Bread’ of passion that the ‘Crust’ of consummation would ‘doom’.

I find it hard not to hear the ways our own moment inflects our hearing of these letters, and the many poems they echo. Dickinson takes solitude and love, contact and separation, out of a relationship of opposition to reveal their strange and paradoxical intimacy. She is surely the laureate of distanced living.

Disappearance, confinement, radical solitude . . . The more ruthlessly Dickinson embraced these conditions, the more she cut off her route to the sanctioned cultural expressions of nineteenth-century womanhood: marriage, motherhood, service to the local community, perhaps even fleeting fame as an author of the kind of popular sentimental poetry and fiction women were licensed to write and read.

Dickinson’s life challenges fundamental and universally shared assumptions, implicit precepts so entrenched in us that we barely know how to question them. It is obvious to us that it’s better to go out and live in the world than to sit in a room and daydream about it, that it’s better to experience real love with another person than to imagine love in solitude.

But are these axioms quite as obvious or unquestionable as we tend unthinkingly to presume? Should a daydreaming life, a life in which the imagined world takes pride of place over the real one, always be seen through the lens of pathology?

D. W. Winnicott suggests as much when he writes of a highly dissociated patient who retreats into daydreams to fend off the risks and agitations of living. He describes the blank, languid reveries in which she wanders into a private fantasy world as ‘an essential state of doing nothing while she was doing everything’.

Dickinson forswore the boundless expanses of the world for the boundless confines of her room and head. ‘The Brain –’, as declared by one of her most famous first lines, ‘is wider than the Sky –’ (no. 632). Her niece Martha, who had grown up in the house next door, wrote of her aunt sitting in her bedroom, holding up an invisible key and miming the locking of the door, saying, ‘Matty: Here’s freedom.’

In the eyes of the world she was ‘doing nothing’, while in her own mind she was ‘doing everything’, travelling fearlessly to the furthest extremities of possible experience – sexual ecstasy, traumatic pain, madness and death.

The contracted space of a locked room is also, Dickinson shows us, an infinite expanse, ‘wider than the Sky’, richer and more variegated than the entire territory of the earth. Her poetry teaches voluntary solitude not as disenchanted withdrawal from the world, but as a movement beyond the restrictions of active life.

***

For Dickinson to go to her Lord in Salem would mean an expansion of her place in the world, but a constriction of her imaginative life. No nineteenth-century bride, however gentle and undemanding her groom, could expect to maintain the permanent and sovereign freedom of a locked room.

And so she made excuses, postponing their union into a receding future, making an erotic virtue of abstinence, until his death rescued her from the dilemma. Her frustrated suitor, who seems to have known little of her poetry, might have spared himself the frustration of being fobbed off had he read just this one, written in 1862, sixteen years before they declared themselves:

I dwell in Possibility –

A fairer House than Prose –

More numerous of Windows –

Superior – for Doors –Of Chambers as the Cedars –

Impregnable of Eye –

And for an Everlasting Roof

The Gambrels of the Sky –Of Visitors – the fairest –

For Occupation – This –

The spreading wide my narrow Hands

To gather Paradise –

(no. 657)

‘Prose’ is Dickinson’s quietly disparaging term for worldly life. She opposes it not to ‘Poetry’ but to a bold synonym for it: ‘Possibility’. To write poetry is to inhabit the house of possibility, its numerous windows opening in all directions onto different vistas.

Equally integral to the house’s architecture are its impregnably sealed rooms, closed off to prying eyes and a roof made of none other than the sky itself. Her visitors are not friends or suitors intruding on her vocation, but the Muses inspiring it, expanding her poetic hands wide enough to encompass Paradise in verbal form.

Still, Dickinson was not quite an absence to Judge Lord. He had known her since she was a child and visited her frequently after he was widowed. As the horrified testimony of her sister-in-law, Susan, informs us, their strange, indefinitely suspended courtship, while evidently unconsummated, included many breathless embraces in the downstairs parlour.

Long before his proposals, Dickinson had warned him obliquely through her letters that nothing could induce her to surrender the Edenic freedom of a locked room.

Dickinson’s ventures to the furthest edges of inner experience evoke the kind of visionary delirium we associate with the religious ecstasy that drove the evangelical projects of her grandfather Samuel. But there is none of Samuel’s religious certainty in Dickinson’s relationship to the cosmic mysteries. Where her grandfather saw a benign and just God directing the course of the world, she perceived a primordial confusion and obscurity. In many of her poems, immortality is conceived not as the blissful reward of the righteous but as the soul’s condemnation to an obscure and malignant endlessness.

In poetry, Dickinson found a different path of inspiration. Where her grandfather embraced the cumbersome responsibility to perform God’s work on earth, she sought transcendence in the airiness and ethereality of words. Her most insistent metaphor for poetic language is snow, the whitest and most evanescent substance, dissolved the instant we try to take hold of it. Poetry cannot be grasped and weighed down; it is the primary medium of antigravity.

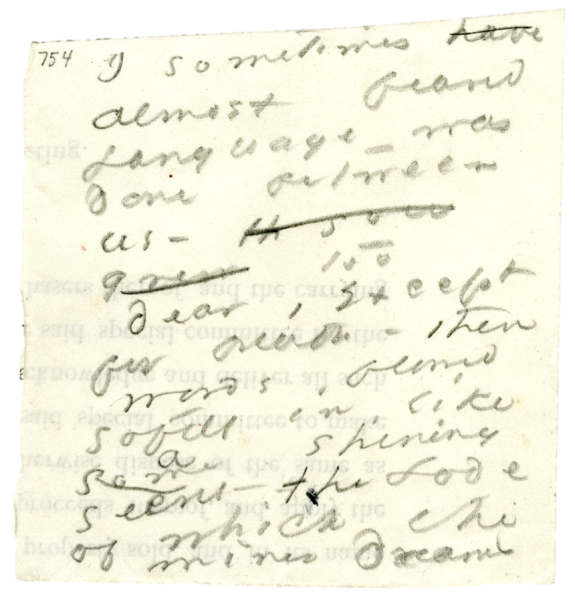

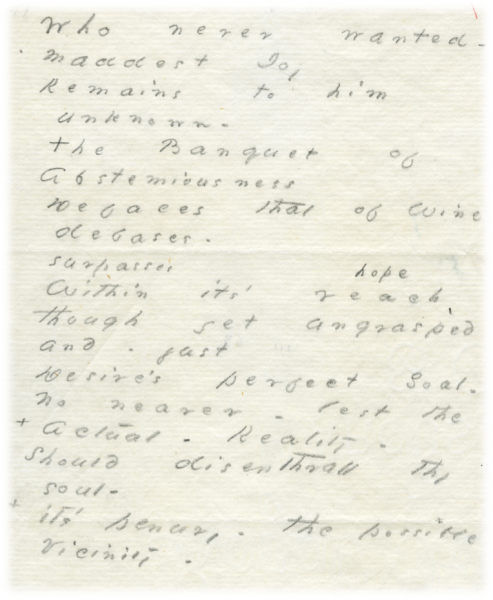

The riches of poetry are in this respect the opposite of those we pursue in profane life. The glory of the poet isn’t that of fame, wealth or any other of the solid external signs of worldly success, but of a kind of poverty, as a short poem of 1877 intimates:

Who never wanted – maddest Joy

Remains to him unknown –

The Banquet of Abstemiousness

Defaces that of Wine –Within its reach, though yet ungrasped

Desire’s perfect Goal –

No nearer – lest the Actual –

Should disenthrall thy soul –

(no. 1430)

In these lines is a striking anticipation of that strange love letter she would send to Judge Lord the following year. ‘Maddest Joy’ is experienced not in attaining ‘Desire’s perfect Goal’ but in wanting it. To realize desire is to betray it – the true banquet is exalted not by wine but by ‘Abstemiousness’.

Dickinson’s abstemiousness, however, was not a tranquil release from desire, but a fevered heightening of desire with a view to its ultimate denial. This may well sound to us like a serviceable definition of torture. Yet Dickinson came to see it as the most ecstatic state we can aspire to. She located the true substance of life in the pure space of the imagination, unsullied by the inevitable compromises and corruptions of worldly reality. We should not doubt her when she tells Lord how much she wants to marry him. Her unrealized passion for him is not some prolonged, sadistic deception, but the expression of her belief in the emotional and spiritual superiority of wanting over having.

To be a poet is to commit to a strange contract with oneself: to amass untold riches in the realm of ‘Possibility’ in order to renounce them in the realm of ‘Prose’ or external reality. This retreat into a more private and invisible glory shouldn’t be mistaken for modesty. It is a breathtaking defiance of gravity, a rising above the laws and conventions that govern life on earth, the establishment of a private dominion within a locked room.

For Cynthia Griffin Wolff, this stance is not only very far from the tired legend of the quiet and unassuming spinster but also the boldest blasphemy, pitting the snowy, weightless creations of the poet against the oppressively solid and unpliable creations of God: ‘In the poet God discovers a creature of His own making who can sing and dance as He cannot.’ The challenge isn’t quite Satanic, however, for the poet does not and cannot seek to outdo God in power and force.

Her only power is a kind of willed impotency. The corollary of her infinite power in the realm of ‘Possibility’ is her inability to make anything happen in the realm of action and change, or what we more commonly call reality. Another poem from 1862 reads as a kind of manifesto for this conception of the poet:

This was a Poet – It is That

Distills amazing sense

From ordinary Meanings –

And Attar so immenseFrom the familiar species

That perished by the Door –

We wonder it was not Ourselves

Arrested it – before –Of Pictures, the Discloser –

The Poet – it is He –

Entitles Us – by Contrast –

To ceaseless Poverty –Of Portion – so unconscious –

The Robbing – could not harm –

Himself – to Him – a Fortune –

Exterior – to Time –

(no. 448)

The ‘familiar species’ of flora lying forlornly outside our front door, like the ‘ordinary Meanings’ of our everyday speech, is dried up, lifeless. The poet’s alchemy involves extracting ‘sense’ – or ‘scents’ – from flowers that had seemed to us bereft of either perfume or significance.

How does she achieve this? Not by creating a picture intrinsically inaccessible to the rest of us, but by ‘disclosing’ some latent scent we hadn’t yet perceived. What we smell when the poet’s words release the flower’s dormant perfume seems to us at that moment so indisputably present, we find ourselves wondering why ‘it was not Ourselves/Arrested it – before –’.

The poet is a kind of convenience device, saving us time and effort. Her abundant gift of disclosure, enabling us to see endless pictures concealed in and around us, ‘Entitles Us – by Contrast –/To ceaseless Poverty –’; in other words, she does it so we don’t have to. Her imaginative wealth bestows on us the right to a kind of imaginative laziness. We can endlessly ‘rob’ her of her pictures, or read her poems, while leaving her none the poorer.

We can steal so freely from her because we aren’t really taking anything. Her store of images is a ‘Portion – so unconscious –’, ‘a Fortune –/Exterior – to Time –’. This is a wonderfully precise evocation avant la lettre of Freud’s definition of the unconscious as ‘timeless’. Nor is the comparison merely impressionistic. The contents of the unconscious, like the contents of the poem, do not exist as objects in our time-bound world. Where money and fame are finite commodities whose loss we cannot always restore, the poetic imagination and the unconscious are infinite resources; we can take from them in the knowledge there’s always more where they came from.

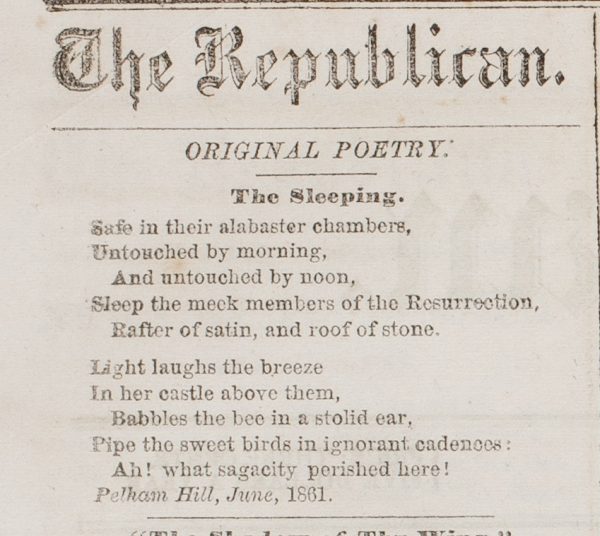

There is a clue here to another of Dickinson’s great renunciations. In addition to marriage and social status, Dickinson refused publication, which would have validated her as a poet in the eyes of the world. Her attitude to publication was rather more ambivalent than her most trenchant pronouncements on the subject suggest. She made initial contact with potential mentors like Bowles and Higginson to sound out their responses to her poetry, and Bowles published six of her poems in his Springfield Republican with her consent. Only five further poems were published during her lifetime.

There are strong hints in the correspondence with Higginson that she was seeking his encouragement to publish. In her first letter, from 1862, she implored him ‘to say if my Verse is alive?’ But when he expressed doubts about how such a dark and obscure poetry would be received by a reading public, suggesting she delay publication, she retorted that the aspiration was ‘foreign to my thought, as Firmament to Fin –’.

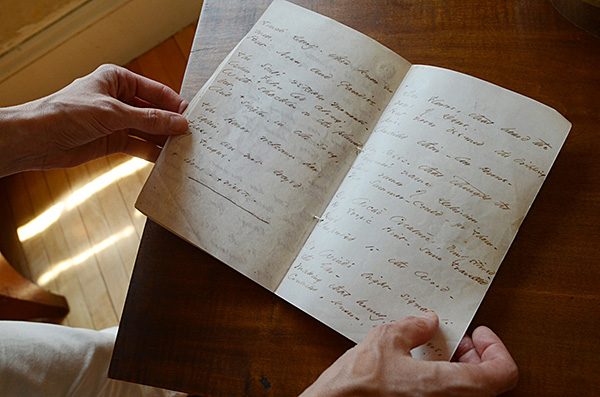

The note of proud pique is undeniable, but perhaps Higginson’s appeal for a more tempered and regular poetic diction will only have confirmed Dickinson’s doubts about the compromises of publication. It is these doubts that might have spurred her creation, between 1858 and 1865, of forty ‘fascicles’ or ‘packets’ containing around 800 poems, posthumously discovered by her astonished sister.

Each fascicle consisted of twenty poems handwritten on four or five folded sheets, carefully bound and threaded together with string. Commentators have argued and puzzled over whether these painstakingly handcrafted artefacts constitute proof of a final renunciation of conventional publication or, on the contrary, a means of ensuring it.

Perhaps the puzzle is a false one. Having invested so much in the presentation and preservation of her poetic legacy, Dickinson kept it hidden while she lived. But she also allowed it to be found after she died, as though she were splitting off the act of publication from any personal striving after fame and fortune. Dickinson wanted the world to recognize her poetry, but wanted equally to ensure that recognition would not be sullied by worldly ambitions and desires. Becoming a celebrity poet in her own lifetime would in her mind have been the most egregious instance of sacrificing the bread for its crust.

Dickinson’s fascicles are a bold gambit from this perspective, for in secretly preparing the way for a posthumous publication she would not live to witness, she shows quiet conviction in the vindication of her poetry’s greatness by posterity. In this way, poetic and personal glory were kept safely distinct from one another.

***

The famous poem 501 of 1862 opens with a confident assertion of the existence of an afterlife: ‘This World is not Conclusion.’ But the world beyond imagined by the poem is hardly the Celestial City of The Pilgrim’s Progress. Contemplating it begets not inspired visions of Paradise, but hazy distortions of the senses. The eternity that ‘stands beyond’ our time-bound world is ‘Invisible, as Music –/But positive, as Sound’. The diffuse waves of sound floating in the ether of the next world are less angelic harmonies than a kind of white noise that ‘beckons, and . . . baffles’.

The extraordinary last lines are a (literally) biting gloss on the evangelical zeal of her grandfather’s traditional Revivalist religion:

Much Gesture, from the Pulpit –

Strong Hallelujahs roll –

Narcotics cannot still the Tooth/

That nibbles at the soul –

In this year of her most prodigious prolificity, in which she produced 365 poems, the bloodiest war ever waged by humankind hitherto was raging through the nation. The Civil War, along with traumatic transformations of industrialization and urbanization, was striking hammer blows against the faith of her grandfather’s generation in God’s luminous and benign ordering of the world.

The turbulence and horror of these seismic upheavals can be seen and heard in the poems’ jarring rhythms and suffocating imagery. Still, we might wonder at how such historically urgent events gave rise not to her active public contribution, but to a retreat into what she called, in a late poem of 1877 (no. 1695), ‘That polar privacy/A soul admitted to itself’. Why would you daydream in a locked room while the world outside burns?

Alternatively, why wouldn’t you? Daydreaming, as I’ve tried to show, isn’t always an expression of melancholy resignation and despair. In her life and work alike, Dickinson reveals the solitary daydream to us as means to the deepest expressions of love, doubt and defiance, as well as psychic survival. In our time of social isolation, she has rendered herself more uncannily contemporary than she or anyone else could have imagined.

Josh Cohen is a psychoanalyst and Professor of Modern Literary Theory at Goldsmiths University of London. His most recent book is Not Working (2019).

This post was written for a colloquium on ‘Voluntary Solitaries’, a research theme about which you can find out more here.