Barbara Taylor in a recent Guardian essay explains the distinction we have been making since the late nineteenth century between solitude — the generally benign state of being alone in one’s own company while remaining grounded in the social and cultural order — and loneliness — the painful state of being unmoored, lost to the world, un-noticed, unseen, cast aside, or caught in the isolation of madness and depression. For millennia ‘solitude’ sufficed for both, poised as it was between ‘profitable Meditation and Contemplation’ (she quotes Robert Burton from the Anatomy of Melancholy) and depression and misery.

A single term to cover both is manifestly inadequate in these times of pandemic because of the painfully evident differences between the solitude of the privileged — those with caring kin, friends, jobs that can be done from home and adequate financial resources for whom social isolation comes as a welcome, or at least bearable, break from a overly hectic life and offers the opportunity for self-improvement — and the solitude, the loneliness, the bereft condition of those who lack a hospitable world beyond the boundaries of the self and for whom social isolation offers nothing but added adversity. The distinction is an existential one.

‘Liveable solitude is underpinned by care,’ Taylor says. And conversely, ‘for a person who has had no reliable carer, solitude is unendurable.’ Solitude without ‘reliable care’ is loneliness.

To some extent the divide between being cared for and not being cared for follows the social and economic fissures of our society. If ‘caring’ means ‘looked after’ or ‘provided for’, the poor, the homeless and the elderly are less likely have their needs looked after than the more prosperous, the sheltered, and the young. And if ‘to be cared for’ means to be regarded by someone, to matter to someone, to be watched over by someone, or, in the now obsolete sense of the verb, to be mourned by someone, that too is, as objective matter, a question of sociology. Is there really someone beyond oneself who cares?

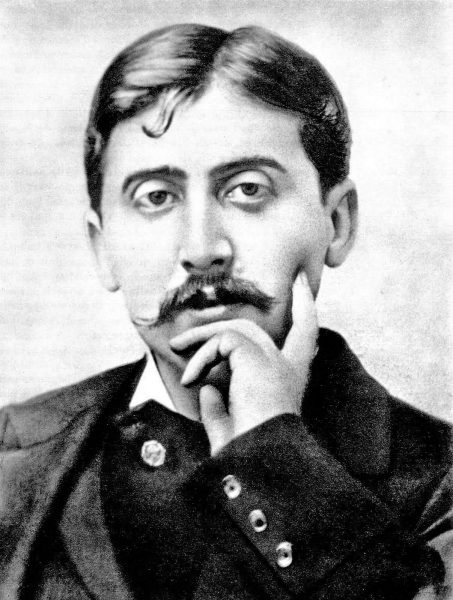

But it is also a subjective question: the deeply rooted feeling that someone or the world cares — or as Taylor puts it, in the past has cared — so profoundly that the carer lives in our psyche. Marcel, the narrator of Marcel Proust’s Swann’s Way was there before psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott.

He is speaking about the ‘one thing necessary to send me to sleep contented.’ He lies ‘in the zone of melancholy,’ wishing ‘he were lying dead’ as the world threatens to slip away. He remembers the ‘untroubled peace’

…no mistress in later years has ever been able to give me, since one has doubts of them even in the moment when one believes in them, and never can possess their hearts as I used to receive, in a kiss, my mother’s heart, whole and entire, without qualm or reservation, without the smallest residue of an intention that was not me alone… [1]

There is, here, the cosmic sense of a ‘reliable carer,’ who cares not just for the individual but for human kind and all who care to be cared for: God (although that is not who Taylor had in mind).

This is the carer of whom the poet of the Psalms sings ‘It is better to take refuge in the LORD, than to trust in humans (Psalm 118); ‘Be strong, be brave, you are never alone’ (Joshua 1:19) The carer of whom the prophet Isaiah speaks: ‘Whether you turn to the right or to the left, your ears will hear a voice behind you, saying ‘This is the way; walk in it”; or ‘fear not for I am with you.’

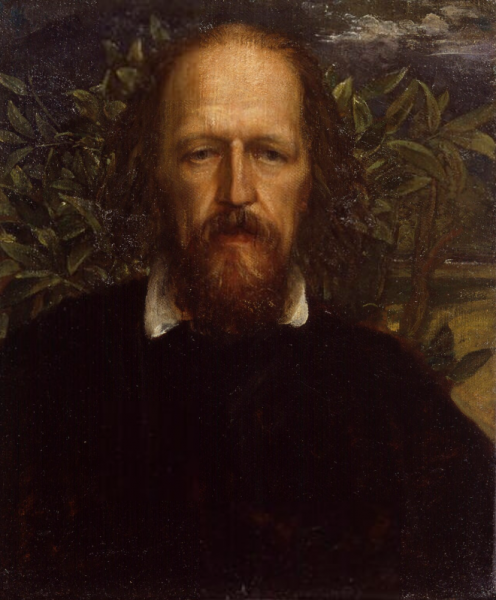

Tennyson’s In Memorium offers a famous modern and more fragile cosmic version:

Who trusted God was love indeed

And love Creation’s final law –

Tho’ Nature, red in tooth and claw

With ravine, shriek’d against his creed –

And finally in John Berger’s account of the human bond with animals we have more secular, that is, a historically and anthropologically grounded, story of this kind of cosmic caring:

With their parallel lives, animals offer man a companionship which different from any offered by human exchange. Different because it is a companionship offered to the loneliness of man as a species.

This ‘unspeaking companionship’, he continues, ‘was felt to be so equal that often one finds the conviction that it was man who lacked the capacity to speak with animals — hence the stories and legends of exceptional beings, like Orpheus, who could talk with animals in their own language.’ And then it wasn’t. ‘To suppose that animals first entered the human imagination as meat or leather or horn is to project a 19th century attitude backwards across the millennia.’ The old equality died with the disenchantment of the modern world.

Dogs, the shaggy subject of this blog, are a part of Berger’s story of a fall from grace: they played their part along with their fellow beasts in the cosmic drama of humans and animals. Perhaps a bigger part than others.

No single species is so deeply imbricated in the mythic structures of the human imagination around the world and through time.

God, when he created the world, had a dog in the California Kato Indian story; dogs guard the dead from Zorastrian Persia to Aztec Mexico. And though they are only occasionally used for meat — the species is not an efficient source of protein — or for leather, they too have lost their cosmic status in the dog shows and bourgeois homes of recent centuries. But in one respect they have maintained a singular sort of consistent companionship for a very long time quite apart of their utility for humans.

They continue to offer companionship — or more specifically a locus for imaging that an animal cares sufficiently to assuage ‘the loneliness of man as a species’ and as singular creatures.

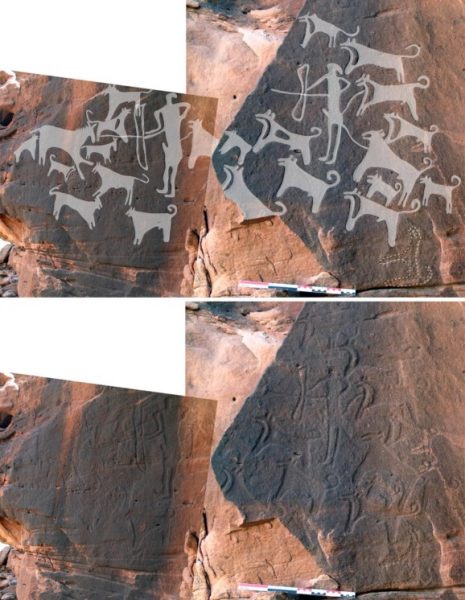

Evolution produced in the dog an animal that lives intimately with humans, a sort of presence that is a minimal condition of companionship. We know for certain that dogs have hung out with us for a very long time and not just as work mates although that too. There were dogs among humans thousands of years before there were sheep to guard or cattle to herd although they did probably help us hunt from the very beginning of the relationship. The oldest visual image we have of an animal doing something with a human rather than being hunted is from rock paintings in the Arabian desert of dogs helping humans hunt that date from c. 9000-8000 BCE.

A friend recently sent me a picture of a Sumerian fired clay brick, 30 cm x 30 cm, from Third Dynasty of Ur (22nd to 21st century BCE) that had been sent to him by the British Museum through Instagram. The cuneiform text, according to my Berkeley colleague Niek Veldhuis’ translation, says ‘Urnamma. king of Ur the man who built a temple for Nanna [the moon god].’

At the bottom left are two small dog footprints, evidence that some mutt, four thousand years ago was walking among the brick makers of Sumer and stepped into one of their brick moulds. Anyone who has ever poured a concrete pad or step will recognise the danger: evidence in clay of the affinity between people and their dogs.

It is perhaps not quite as uncanny as the footprints, stretching over 50 meters, made in clay and preserved in dissolved limestone, of a boy who visited the Chauvet caves 25,000 years ago, five thousand years after they were painted, next to the footprints of a canid. It would be delicious to image the boy carrying a torch — scientists date his visit from the soot left behind — and his dog out for an afternoon’s exploration. But the canid might have been a wolf or proto-dog, a wolf-dog far enough along its evolutionary path to want to be with humans; it also might have left its prints earlier or later.

But in the case of the Sumerian brick we know there was a dog around a human brick maker. Maybe it came bounding onto the drying bricks after the workers left for home. Or maybe it was wandering around during the work day; or maybe it sat all day with the brick maker. We do not know of course but we do know that there are many dogged bricks like it.

There is one at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology with four paw prints from the same period on which the nails of the dog’s claw left its imprint; we have one with three dog footprints from a few centuries later in the Hearst Museum at Berkeley; another at Penn from the period of Nebuchadnezzar, 626-529 BCE, rough speaking when the Jews were in exile there. And there are more such tiles in the world’s museum and no doubt also in the ground.

But tiles with paw prints are not evidence for how we might imagine dogs as caring for us. For this I leap forward almost four millennia to a story from classical antiquity in which a dog came to play a new part around 1500. Michelangelo has a role to play in this history of the emotions.

A shaggy dog story of how I came to this. The philosopher Hagi Kenaan’s Photography and its Shadows (Stanford University Press, 2020) is a meditation on Nietzsche’s death of god — the collapse of a cosmically given ground of meaning — and specifically on his image of ‘Buddha’s shadow in the cave’ as ‘an allegory of the dramatic transmutation of the condition of the visual that allows the shadow to endure as an independent entity.’ As part of her study she is interested in welcoming and bidding farewell, to ‘negotiating the dimensions of transience and finitude.’

My interest in her work lies in the aloneness of the one left behind but also in the comfort that one might feel at the prospect of being missed. It is about imagining that someone cares, if not the cosmos.

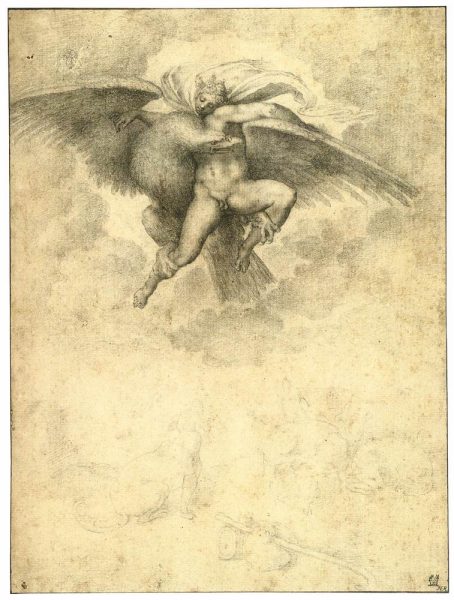

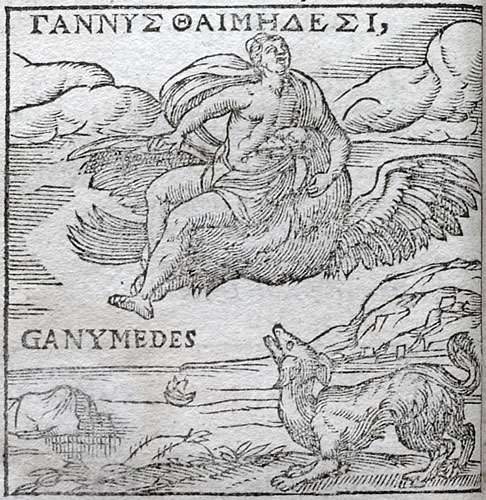

Kenaan reports that she asked the Renaissance art historian Giancarla Periti whether she could think of any interesting farewell gestures. After a while Periti came up with Correggio’s ‘Abduction of Ganymede’ (c. 1530s). This was, Kanann responded, an unlikely suggestion: ‘Ganymede was abducted by Zeus… does this involve a farewell?’ ‘Listen to the barking in the painting’ she replies. ‘The dog is the one saying goodbye.’

I have my doubts this is what the dog is doing; a dog is more likely to bark when its master returns than when she leaves. More likely it is barking because an eagle has disturbed his peace and abducted the boy he works with. An upset bark; an angry bark. But I do not want to push the point but rather ask ‘why is the dog there in the first place?

No ancient image of the beautiful young shepherd — or in other versions hunter — with whom Zeus fell in love and sent an eagle to abduct has a dog. Nor is one mentioned in any of the many versions of the story we have from antiquity. Correggio’s painting does not tell us anything substantive about the relationship of the dog and the human being swept off by an eagle. The putative shepherd or hunter of legend in this painting is barely pubescent not up to such adult pursuits; he is too young to have a dog.

Michelangelo’s ‘Rape of Ganymede’ is more revealing of the relationship between boy and dog.

In 1532 the fifty seven year old artist fell in love with a beautiful young nobleman Tommaso dei Cavalieri and gave him as a gift a series of drawing on classical themes, among them one about Zeus’s passion for the young shepherd whom he abducted from his fields to be with him on Olympus. The image he produced was widely copied. In the left foreground, seen only very faintly, is a dog; centre and right is a shepherd’s crook; further up and right are sheep.

The dog cares that the young man with whom he has shared a life is gone. It is not an allegorical dog; it means nothing.

We can be pretty sure of this because when a version of Michelangelo’s drawings appears in Andreas Alicato’s Emblemata, the most popular and widely translated book of its kind in Europe, a collection of over 200 images with an explanation of what each one means, nothing is said about the iconography of the dog. He is just looking up at his abducted master being borne away by an eagle and barking as any dog might do.

Ganymede, on the other hand, is an allegorical figure, there under the rubric ‘Joy is to be found in God.’ There isn’t even a dog in the first, 1531 edition, but after it appears in 1551 it is there to stay. I am not sure but given how often the Michelangelo drawing was copied that he was the ‘skillful illustrator’ whose dog now makes its way into the image. I quote from the fullest, the 1621 edition of Alciato:

See how the skillful illustrator has shown the Trojan boy being carried through the highest heavens by the eagle of Jove. Can anyone believe that Jove felt passion for a boy? Explain how the aged poet of Maeonia [Homer] came to imagine such a thing. It is the man who finds satisfaction in the counsel, wisdom and joys of God who is thought to be caught up into the presence of mighty Jove.

One moment the dog and the solitary shepherd are guarding sheep together. The next moment the shepherd is gone, his cloak and crook left on the ground with his dog and his sheep. Any dog would bark farewell and look forlorn. This dog — the dog whom we imagine, through the visual arts, to care about humans — has a past and the future. A moment in the history of the emotions. Somewhere between 1300 and 1305.

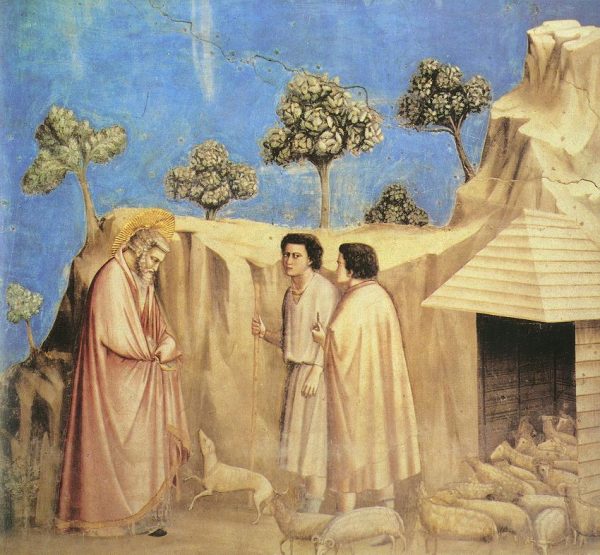

To art historians the date will come as no surprise; Giotto’s ‘Life of the Virgin’ in the Arena Chapel in Padua. He was the master, as Tim Clark recently wrote — the Shakespeare — of western art in telling us what visualization is for, what ‘job of exemplification it was called upon to perform.’

Giotto was there at the birth of the western tradition of representing emotion visually, of representing to ourselves — to take the case in point, what it would look like to have a dog care. This fresco, completed in 1305, is probably the first work most of us will have seen in a class in the history of modern western art. Vesari claimed in his sixteenth century Lives of the Painters that had Giotto had initiated ‘the great art of painting as we know it today.’

The second image on the upper tier of the south wall is a scene of grief, humiliation and loneliness. The pious Joachim, husband of Anne — mother-to-be of the Virgin — has fled into the dessert after the priests of the temple rejected his sacrifice because in their eyes Anne’s barrenness reflected God’s displeasure with him.

He is dejected. He meets the shepherds who are looking after flocks that he owns (‘Joachim among the Shepherds’). They avert their eyes, uncertain what to make of their boss, surprised at the presence of so august a figure from the far off city; un-willing to engage.

The scene had been frequently represented in Byzantine art and in western illuminations. But Giotto’s version is the first with a dog. Not an allegorical dog; not a dog that is doing its work herding sheep. Not a dog in the painting for its reality effect or to represent faithfulness or courage. It is there for its emotions; it exemplifies attention to this human; it notices Joachim and looks him in the eye. The dog has left his sheep and rushes up to the downcast stranger — maybe he knows him but probably not; the rich owner from the city who owns the flock probably does not come out to the fields. The dog gets up on its hind legs; looks up at Joachim; wags his tail in greeting.

It recognizes him as a man. He makes a connection; and we can imagine him caring.

The painting brings to mind an essay of Emmanuel Levinas in which the philosopher speaks about a dog named Bobby who recognizes him and his fellow prisoners in a Nazi camp as human by greeting them when they return from forced labor. The dog recognizes them as humans even if their German guards do not [2].

Joachim falls into a deep sleep and an angel appears to tell him that Anne has conceived and asks him again offer God a sacrifice. Watching him — on the rock between the stony world of the dessert and the brilliant blue of the world of the imagined world to come — is the dog.

Much more to be said about this painting of course but let me just say minimally that here, at the origin of a new kind of painting is a new way of representing the emotional bond of human and animal.

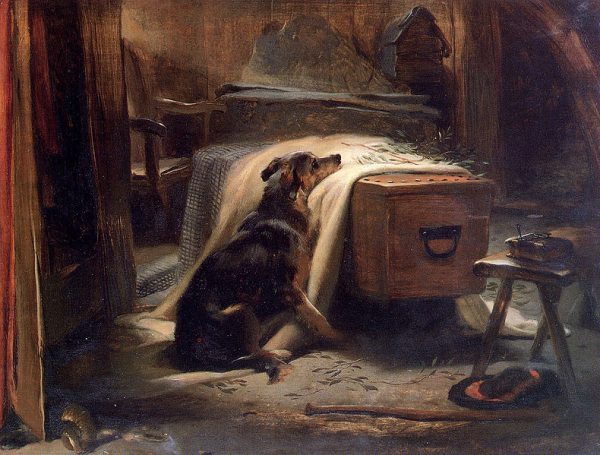

The afterlife of the dog who notices a lonely human and cares runs from Giotto through the Ganymede images I have talked about, through hagiography — the dog who fed St. Roch, patron saint of plague victims, after humans had cast him out of the city (Strozzi’s 1640 image is one of hundreds) — on to the dog as the witness to a lonely death. Landseer’s ‘The Old Shepherd’s Chief Mourner’ is probably the most famous nineteenth century image in that genre.

My claim is of course not that a dog can replace the deeply seated carer that lies at the foundation of the psyche of which both Proust and Winnicott speak. Nor am I arguing that a dog can provide the kind of services that make life in solitude livable. But the dog who offers a ‘reliable carer’—another creature who is watching when one is alone with oneself and keeps unbearable loneliness at bay – has a long history. It is perhaps the last survivor of the world that Berger conjures up; the world in which animals more generally guarded against cosmic loneliness.

[1] Marcel Proust, Swann’s Way (New York: Modern Library, 2003), pp. 258, 261.

[2] ‘A Name of a Dog’, in Difficult Freedom: Essays on Judaism (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012).

Thomas Laqueur is Professor of History at University of California Berkeley. He is the author of Solitary Sex: A Cultural History of Masturbation (2003) and The Work of the Dead: a Cultural History of Mortal Remains (2015).