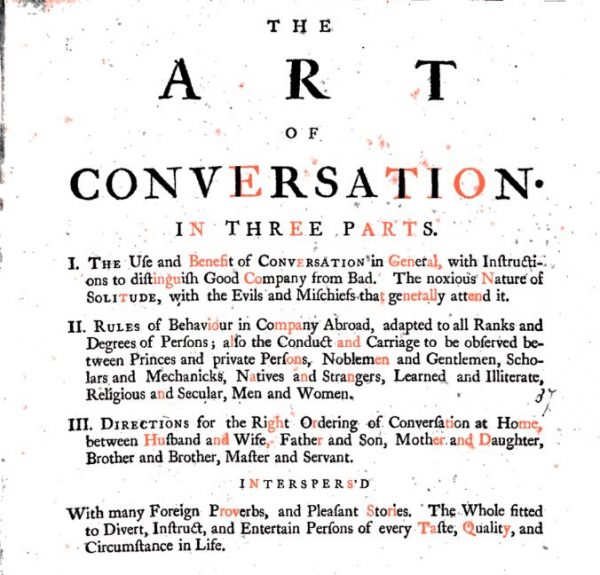

In 1574 an Italian writer named Stefano Guazzo published The Art of Conversation (English translation 1581), a text best known for its influence on European manners. The book features a dialogue between a character named Guazzo and his friend, Annibale. The Guazzo character is suffering from melancholy, which he hopes to cure by retreating into solitude:

…the company of many is grievous unto me, and… contrariwise, solitariness is a great comfort and ease… for I feel it a great travail to my mind, to understand other men’s talk, to frame fit answers thereto… But when I withdraw myself into my lodging either to read or write, or to repose myself: then I recover my liberty, and let loose the reins thereof, in such sort, that having not to yield account of itself to any, it is altogether applied to my pleasure and comfort.

Annibale takes issue with his friend, deploying Galenic humoural theory to caution Guazzo against the dire medical consequences of social withdrawal. Humoural theory held that healthiness depends on a balance between four bodily fluids (humours): blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. Melancholy arose from a superfluity of black bile, to which solitaries were famously prone. Annibale warns Guazzo (in an odd choice of metaphor) that ‘like unto the fly which flies about the candle’, by opting out of society Guazzo will not ‘consume and starve’ his melancholy but ‘nourish’ it:

For thinking to receive solace by means of a solitary life, you fill yourself full of ill humours, which take root in you, and there lie in wait ready to search out secret and solitary places conformable to their nature…and as hidden flames by force kept down are most ardent, so these corrupt humours, covertly lurking, with more force consume, and destroy the faire palace of your mind.

Not satisfied that he has yet persuaded Guazzo to abandon his reckless plan, Annibale goes on to regale his hapless friend with tales of solitaries who, becoming ‘lean, forlorn, & filled full of putrified blood’, ‘fall into such vehement and frantic fancies [fantasies], that they have given occasion to be laughed at, and pitied’, until finally they terminate their miseries by ‘making themselves away by the means either of water, or fire, or sword, or by throwing themselves headlong from on high’.

The prospect must be terrifying; but Guazzo stands his ground, insisting that solitariness is a ‘Paradise’ to him and marshalling in his defence the poet Petrarch’s famous championship of solitude in his De Vita Solitaria (1346-56). Annibale is ready for this however, pointing out that ‘notwithstanding all the praises he [Petrarch] attributes to the solitary life’, the poet fully acknowledged that ‘without Conversation our life would be deficient.’ For Petrarch, Annibale continues, ‘was no enemy to good company’; nor should Guazzo be so, lest he end up mad or dead or, worse still, subhuman. Solitude was a ‘poison’ for which social interaction was the essential ‘antidote’:

And therefore it may justly be said, that who so leaves the civil society to place himself in some solitary desert, takes as it were the form of a beast, and in a certain manner puts upon himself a brutish nature.

Solitude is one of the most complex concepts in our cultural repertoire. Endlessly protean, its meanings have varied radically between periods and settings, or even within the same period and setting. Tracing its history is very challenging. But certain texts offer illuminations. Guazzo’s Art of Conversation is one such text. The ‘solitude’ decried there is that of the social refusenik, the individual who for a variety of reasons – spiritual, intellectual, temperamental or, as in Guazzo’s case, medical – turns his back on human companionship in favour of an isolated existence.

Solitaries of this ilk had been regarded as unnatural, immoral and pathological for millennia. Exceptions were acknowledged, but only among the god-like – saints, philosophers, creative geniuses – and even these were not exempt from criticism. For ordinary mortals, a reclusive life was malign and deeply perilous.

Yet alternative versions of solitude were also available. When, in The Art of Conversation, Annibale rightly points out that Petrarch did not eschew ‘good company’ he understates the poet’s position. In fact, good company was at the heart of Petrarch’s solitariness.

Book 1 of De Vita Solitaria describes his ‘solitude’ as a state of warm companionship with a small group of learned male friends (but no women, who Petrarch regarded as ‘poisonous’ to solitude), reading and conversing together ‘without complaint or grumbling, without envy or treachery’. ‘No solitude is so profound, no house so small, no door so narrow,’ Petrarch declared, ‘but it may open to a friend.’ To those critics who, knowing his reputation for reclusiveness, had charged him with misanthropy, he replied that he had never urged anyone to ‘despise the laws of friendship. I urged them fly from crowds and not from friends.’

Yet in Book 2 of De Vita Solitaria Petrarch praised hermits and other holy men whose total isolation was ‘most favourable’ to divine communion: an ambivalence reproduced by many early modern writers as they shuttled between a ‘solitude’ of absolute aloneness and the convivial solitude of likeminded intimates. In 1518 the great humanist scholar Erasmus highlighted this ambiguity in an imaginary dialogue between a Carthusian monk and a soldier. Like Annibale in The Art of Conversation, the soldier reproves the monk for his unnatural ‘Lonesomeness’, to which the monk replies that monastic life is necessary for his ‘perpetual study of Innocency’,

…and besides, if you call that Solitude which is only a retiring from the Crowd we have for this the Example, not only of our own, but of the ancient Prophets, the Ethnic [pagan] Philosophers, and all that had any Regard to the keeping a good Conscience. Nay, Poets, Astrologers, and Persons devoted to such–like Arts, whensoever they take in Hand any Thing that’s great and beyond the Sphere of the common People, commonly betake themselves to a Retreat. But why should you call this Kind of Life Solitude? The Conversation of one single Friend drives away the Tedium of Solitude. I have here more than sixteen Companions, fit for all Manner of Conversation… Do I then, in your Opinion, live melancholy?

To ‘live melancholy’ is what we now call ‘loneliness’: a condition widely described as a major health risk in terms not wholly unlike those employed by Annibale in The Art of Conversation. We have no words today for a Petrarchan solitude of friendship, although perhaps that is what social media offers to some of us. The language evolves[1]; but while the vocabulary and its historical settings have changed, cultural anxiety over solitary selfhood, the ‘I’ in relation to itself and others, is stronger than ever. As in Guazzo’s day, ‘solitude’ remains a perennial concern, and a perpetual puzzle, at the heart of western culture.

[1] I describe one of the biggest shifts, the abandonment of a discourse of moral evaluation, here.

Barbara Taylor is Professor of Humanities at Queen Mary University of London and Principal Investigator on the ‘Pathologies of Solitude’ project.