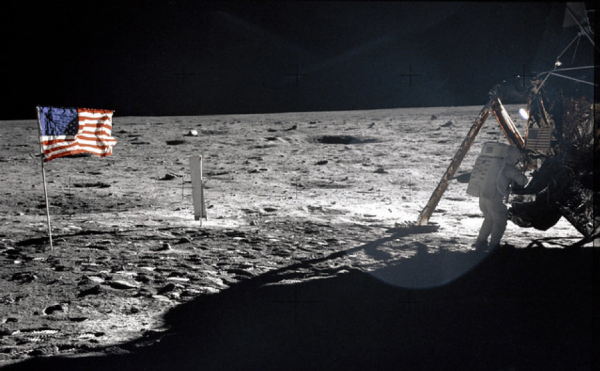

At 17:44 on 20th July 1969, the occupants of NASA’s mission control centre in Houston TX sat and waited with bated breath. Their mission to land a man on the moon for the first time in human history had begun four days earlier with the lift-off of the Apollo 11 spacecraft, and it was now entering one of its most critical phases, as the main command module Columbia separated from the lunar module Eagle and astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin ‘Buzz’ Aldrin began their descent towards the planned landing site in the southern Sea of Tranquility. Less than three hours later, the lunar module landed successfully and a media storm ensued, with worldwide broadcasts focusing an intense interest onto Armstrong and Aldrin’s historic first steps on the moon.

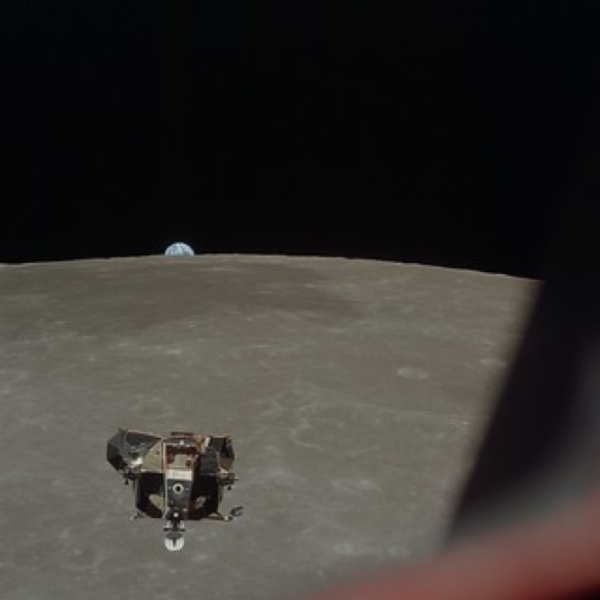

Away from the spotlight, however, there was a third member of the Apollo 11 crew. Michael Collins, lesser-known both now and then for his less visible role in the mission, remained in lunar orbit, maintaining the command module Columbia and preparing for his colleagues’ return. Collins would spend a total of 76 hours in orbit, and whilst Armstrong and Aldrin were taking their first steps on the lunar surface, Collins was achieving an historic first of his own, becoming the first astronaut to orbit the far side of the moon alone.

Each lunar revolution took a little more than two hours, and Collins spent almost 48 minutes of each two hours on the dark side of the moon. Already physically separated from the earth by 250,000 miles of space, he now slipped periodically out of contact with both headquarters in Houston and his fellow astronauts working on the surface of the moon. ‘I am alone now’, he later wrote of that first 48-minute stretch, ‘truly alone, and absolutely isolated from any known life…

…I am it. If a count were taken, the score would be three billion plus two over on the other side of the moon, and one plus God only knows what on this side’.

The feeling of isolation was one that Collins had known to expect, and he suspected that his particular experience of it would come to define the way others viewed his time in space:

I know from pre-flight questions that I will be described as a lonely man […] and I guess that the TV commentators must be revelling in my solitude and deriving all sorts of phony philosophy from it.

He was not wrong in this regard, disappearing behind the moon for the first time with NASA’s own commentary team solemnly intoning, ‘not since Adam has any human known such solitude as Mike Collins’.

He joked about this in later years, suggesting ‘some very slow news day’ as the press’s motivation for ‘announcing that here I am, the loneliest man in the whole lonely universe, with an orbit so lonely that my loneliness exceeds that of all lonely souls before me. Ridiculous.’ He even wrote a faux love letter to the command module Columbia for the 50th anniversary of the moon landing, asking ‘How could I be lonely? You have me and I have you […] Now that I have gotten rid of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin and sent them down to frolic on the surface 60 miles below, the two of us can finally be alone’.

But Collins also maintained a more pragmatic argument against those who saw his particular experience of solitude as something unique and almost romantic. ‘In terms of distance’, he wrote, ‘I am much more remote, but in terms of time, lunar orbit is much closer to civilized conversation than is the mid-Pacific’:

Although I may be nearly a quarter of a million miles away, I am cut off from human voices for only forty-eight minutes out of each two hours, while the man in the skiff – grazing the very surface of the planet – is not so privileged […] I feel simultaneously closer to, and farther away from, Houston than I would if I were on some remote spot on earth which would deny me conversation with other humans for months on end.

For Collins, then, it was a psychic connection rather than a physical one that helped him to bear his solitary time in space. His words reveal confidence in a clockwork mission schedule, one that allowed him to travel further away from humanity than any man or woman had ever done alone, safe in the knowledge that his travels were finite and his connection to others was only ever 48 minutes away.

This knowledge and faith in connection translated into his understanding of Apollo 11 as a collective mission. From his lunar orbit, Collins wrote:

Far from feeling lonely or abandoned, I feel very much a part of what is taking place on the lunar surface. I know that I would be a liar or a fool if I said that I had the best of the three Apollo 11 seats, but I can say with truth and equanimity that I am perfectly satisfied with the one I have. This venture has been structured for three men, and I consider my third to be as necessary as either of the other two.

Pragmatically, Collins was exactly right: his training had been significantly different from Armstrong’s and Aldrin’s and his maintenance and piloting of the command module were vital elements of Apollo 11’s success. But his belief in the necessity of all three men to the mission had other, more ominous connotations for Collins as he waited in orbit to be re-joined by his colleagues:

My secret terror for the last six months has been leaving them on the Moon and returning to Earth alone […] If they fail to rise from the surface, or crash back into it, I am not going to commit suicide; I am coming home, forthwith, but I will be a marked man for life and I know it.

All three members of the Apollo 11 team became vulnerable to this ‘mark’ as soon as they joined the mission; the loss of any one of them would have marred its legacy. But Collins’ ‘secret terror’ speaks to a different kind of solitude than that being imagined by the TV commentators watching from Earth – namely, the fact of being sole or unique. His part in the mission had changed his identity and he was no longer the individual he had once been. Instead he was, and would forever be to the public, part of a team of astronauts whose lives were inextricably intertwined by the parts they played in Apollo 11’s mission to the moon.

And so this fed into a fear of solitude that did not come from being alone in the dark void of space, but rather from the potential for a conspicuous future of aloneness in a world inhabited by everyone but the two men who shared his collective identity. Collins did not worry about being alone but staying alone. He enjoyed his isolation in space, feeling it ‘powerfully – not as fear or loneliness – but as awareness, anticipation, satisfaction, confidence, almost exaltation’. But his was a vision of community and togetherness, and a life without Armstrong and Aldrin would have branded him more solitary than any time on the dark side of the moon ever could.

Clare Whitehead (@clareapparent) is the project manager for the ‘Pathologies of Solitude’ project.