I never thought my research on 18th-century solitude and health would gain such resonance, and never wished it would in these circumstances. Poetry plays a distinctive role in understanding a society’s differing relationships with solitude. Many also turn to the poetic voices of the past in the face of a loss of normalcy.

In previous research, I’ve focused on how these voices of the past are turned to as a means of coping with death and grief. These poetic voices can similarly become a means of coping with the new normal of isolation, giving a larger historical perspective to our socially-distanced solitude and showing how this history of solitude can perhaps help us to cope with collective feelings of anxiety, grief, and loss.

From daily mentions of social distancing, enforced quarantines, and even down to ‘Stay Home’ Instagram stories, solitude is currently engrained in our daily discourse and is intrinsically connected to health.

This connection of solitude and health is far from new.

Solitude was often referred to as a ‘nurse’ in poetic works across the eighteenth century. The term ‘nurse’ derives from ‘nourice’, a wet nurse, or a woman who takes care of a child. At the root of the phrase is a maternal sense of nourishment and care. Solitude was seen as the nurse of many things in eighteenth-century poetry: sense, contemplation, joy, wisdom, woe, but most presciently for our current time, care.

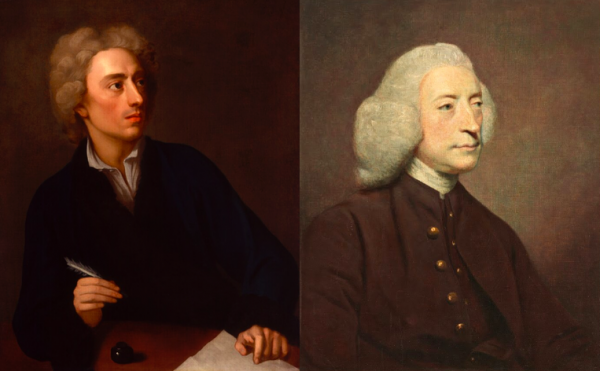

As a ‘nurse’, solitude was directly linked to concerns about health and wellbeing. Alexander Pope called it ‘wholesome solitude, the nurse of sense’ in his ‘The Fourth Satire to Dr John Donne Versified’:

Bear me, some God! Oh quickly bear me hence

To wholesome solitude, the nurse of sense:

Pope’s use of ‘wholesome’ here is important for how we should be framing our current solitude. Wholesome in Pope’s sense meant ‘conducive to or promoting (mental and physical) wellbeing’ and ‘having the property to restoring physical health’: there is a sense of solitude as being both medicinal and curative here. This solitude is also closely linked to ‘Contemplation’, with Pope calling on a larger poetic history of the two being co-dependent. Contemplation’s ‘ruffled wings’ are pruned and restored as Pope imagines solitude as a restorative space for recovery.

This solitude, with its nursing of sense, is a space within which the mind can recover and develop a ‘free soul’ to look ‘down to pity kings’, pushing the mind outside society’s hierarchy. Though the results of this solitude are philosophical, the language used to describe the state of solitude is distinctly health-related. The language of good health is intrinsically connected to this process of solitary nourishment.

Right: Dr John Armstrong, by Joshua Reynolds. Oil on canvas, 1767. Morgan Thomas Bequest Fund 1934, © Art Gallery of South Australia.

John Armstrong, in his 1744 poem The Art of Preserving Health, called solitude the ‘sad nurse of care’:

Chiefly where Solitude, sad nurse of Care,

To sickly musing gives the pensive mind.

What is most pertinent to our times is Armstrong’s play on the word ‘care’. The word has roots as meaning both concern & sorrow:

- Mental suffering, sorrow, grief, trouble. Obsolete.

- Burdened state of mind arising from fear, doubt, or concern about anything; solicitude, anxiety, mental perturbation; also in plural anxieties, solicitudes. †withouten care: without doubt. †to be in care: to be troubled, anxious, concerned.

- Serious or grave mental attention; the charging of the mind with anything; concern; heed, heedfulness, attention, regard; caution, pains.

- Charge; oversight with a view to protection, preservation, or guidance. Hence to have the care of, etc. to take care of: to look after.

Solitude in this formulation can be read as nourishing care in our more common use of the term in reference to nursing as ‘caring for others’, but also as fostering a sense of anxiety and sorrow. It has a distinct duality that has deep resonance with our current times.

This poetic history of solitude speaks to our current experiences of it. As the ‘sad nurse’, solitude is both caring and dangerous: its duality means that it is inherently caring and nourishing but also has the potential to lead to the darker consequences of too much musing. Just as Pope’s wholesome solitude leads to the restoration of contemplation, Armstrong’s ‘sad nurse’ leads to sickly musing and melancholy.

Our current calls for distancing have a similar duality to them – they have a distinct sense of anxiety and sorrow, but at their root is care for others. That is key to remember.

While this current period of solitude has the capacity to lead to a sickly musing, at its root is a history of caring and nourishment that it perhaps more easily forgotten than solitude’s more well-known connections with melancholy. It’s worth remembering that this solitude, as it often has been in the past, is linked to a nursing and caring for ourselves and those around us.

Some poetic voices to turn to (and transport you) while staying in place

Mary Whateley Darwall – ‘The Pleasures of Contemplation’

Lavinia Greenlaw – ‘The built moment’; ‘A difficulty with words’

Seamus Heaney – ‘A Herbal’

John Keats – ‘On the Sea’

Alexander Pope – ‘The Fourth Satire to Dr John Donne Versified’

Denise Riley – ‘Composed underneath Westminster Bridge’; ‘Listening for lost people’

Rainer Maria Rilke – ‘Water Lily’

James Morland (@jameswmorland) is a postdoctoral research fellow on the ‘Pathologies of Solitude’ project at Queen Mary University of London.