In 1976 Canada’s awarded its premier literary prize to a novel about a sexual relationship between a woman and a bear [i]. For a country routinely described as boring, Canada displays a surprising penchant for such flashes of sublime weirdness (witness the film auteur David Cronenberg).

Bear, by Marian Engel, stormed the bestseller lists in Canada and the USA. A UK edition was published by Pandora Press in 1988 but it got little attention. Perhaps the book’s ‘peculiarly Canadian’ theme (as one reviewer delicately put it) was a turn-off; I regularly press copies on British friends, none of whom have admitted to reading it.

Lou, Bear’s human protagonist, is a librarian-archivist working at a Historical Institute in a large Canadian city. She is a ‘mole’, a lonely, flabby thirty-something who spends her days burrowing amidst dusty files in the Institute basement. Once a week, she and the Institute’s Director cheerlessly couple on her desk. Then one summer she is sent off to catalogue a library bequeathed to the Institute by the descendant of a colonial family.

The family home housing the library is on a remote island in the northern bush. Lou will be there on her own, with back-up only from Homer, a mainland storekeeper who boats in supplies now and then. The prospect of this wilderness existence intoxicates her – and then she discovers the bear.

The bear is a pet of the deceased estate-owner. Lou will feed him during her stay while his future is decided. He lives at the end of a chain behind the house, and at first Lou is dismayed by his large smelly presence. But he’s a gentle brute who – so long as she shits beside him every day, so that he can smell her odour – will do her no harm. They become buddies, swimming together and hanging out in the study where Lou does her cataloguing. The physical companionship is welcome; Lou enjoys rubbing his pelt, tickling him. Then one evening, stretched out in front of the fireplace, she begins to masturbate. The bear decides to join in and starts to lick her:

The tongue that was muscular but also capable of lengthening itself like an eel found all her secret places. And like no human being she had known it persevered in her pleasure. When she came, she whimpered, and the bear licked away her tears.

The relationship becomes an idyll, with the woman joyously exigent (‘eat me bear!’) and the bear wonderfully obliging (especially when she lathers herself in honey). But there’s a pressure inside Lou for more. The bear does not desire her, he is merely grooming her. ‘Claw out my heart, bear’ she whispers, tempting him. ‘Tear my head off.’

She dreams about the Devil and aggressive sprites who want to ‘eat her breasts off’. On one occasion she tries to mount the bear, to entice him to penetrate her, and afterwards feels guilty and wretched. ‘She had gone too far. There was something aggressive in her that always went too far.’

Then one evening, as they are snuggling, the bear becomes aroused. Lou, profoundly excited, crouches down before him – and the bear reaches out a paw and rips her back. The moment of violence is extraordinarily shocking. But the violence is not inside the bear – who feels no rage, no malice, is only doing what excited bears sometimes do – but in Lou, who has yearned for this physical explosion of destructive energy.

She is badly torn; looking at herself in the mirror the next day she knows that she will always carry the scar of her lover’s claw. But with this wounding she is purged of the depressive misery that has haunted her. She feels clean, peaceful, ready for anything. She returns to the city, while the bear goes to live with a local indigenous woman. Lou waves goodbye as they part but he doesn’t look after her: ‘She didn’t expect him to.’

Bear has been read in many ways: as a manifesto for female sexual empowerment; as a parody of Canadian wilderness literature; as pornographic pastoral. It’s probably all of these, but one of the keys to the novel comes early on when Lou compares her situation to Robinson Crusoe. ‘People get funny up here when they’re too much alone,’ Homer the shopkeeper tells Lou, and the perils and pleasures of solitude are a central theme.

Lou has a passion for solitude. In the city, this craving has merely left her lonely; but now, stuck on the island with her ursine beau, she has found the perfect solitary scenario. ‘Not everyone is fit for silence,’ she thinks, but her bear emphatically is, affording her company and pleasure while leaving her quietude unbroken. The bear licks and probes her, but he does not intrude upon her. She can ‘paint any face’ on him that she likes, she reflects, since his actual expressions mean nothing to her, as hers mean nothing to him. With him, she has that accompanied aloneness that animals, especially dogs, have so long provided to human solitaries.

*

The female solitary is a controversial figure. What do women get up to when they’re on their own? One of the few hostile reviewers of Bear slated it as ‘spiritual gangrene… a Faustian compact with the Devil.‘ This man may have been out of sync with majority opinion but the link between female eroticism, solitude and the Devil is ancient.

Throughout western history solitude has been regarded as morally hazardous for both sexes, but the dangers have always been judged far greater for women than men. The Devil – an omnipresent peril for solitaries until well into the eighteenth century – was especially on the lookout for lone women whose weaker natures presented opportunities. Withdrawal from male observation posed the greatest risk. ‘The farther a woman goes from her husband, the nearer she approaches to her destruction,’ the 14th century poet Petrarch wrote in reference to Eve’s diabolic seduction.

Nowhere in Genesis is Eve depicted as alone when she picks the forbidden fruit, yet nearly all commentators on the Fall portrayed her as having wandered off from Adam. In Paradise Lost John Milton depicts Eve cajoling Adam into gardening apart for a time, with its inevitable disastrous consequence. Erotic images of Eve’s serpentine corruption proliferated.

Lou’s bear is no diabolic lothario, but her imagination makes him into a perfect lover, a virtuoso of masturbatory ardour. This too has a long history. Solitude is a notorious breeder of autoerotic fantasies. In the eighteenth-century these became the focus of a widespread moral panic, and a rich source of pornographic imagery.

The solitary female novel-reader was a particular object of moral opprobrium and sexual fascination. A woman alone in her boudoir with one hand clutching a romantic novel while the other stroked her genitals was a favourite of porn artists. Small dogs often featured, sometimes performing cunnilingus while the woman read.

Bear is a richly comic commentary on this pornographic tradition, as well as a contribution to it. But it has another link to the solitude tradition. For Lou’s erotic adventure is also a ‘high, whistling communion’ with the spiritual. Working her way through the old library, she discovers that its owner was a collector of ursine legends. Notes drop out of books telling her about the bear as the ‘Dog of God’, a ‘Great Spirit’ ‘older and wiser than time’.

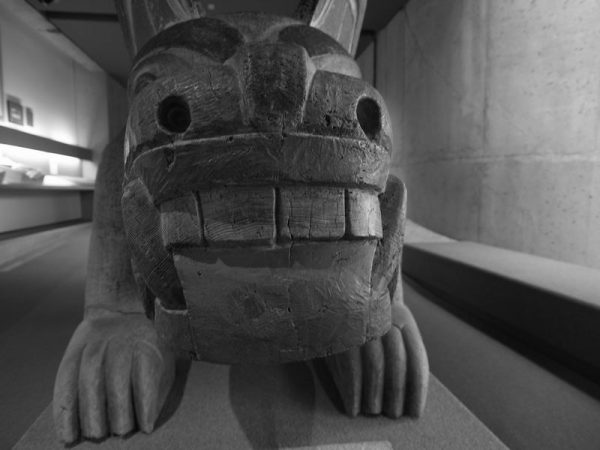

Bear was originally titled The Dog of God. Marriages between women and bears had been a recurrent myth (a Haida version of this gave Engel the conclusion to her novel.) The sacred lore fills Lou with reverent joy. Her affection for her bear deepens into a passion; she ‘thought sometimes that he was God’. She yearns to give herself to him completely, to couple with her ‘well-beloved honey-eater’ who, unlike any of her human lovers, has fulfilled her, body and soul.

Eroticised religiosity and the sacralisation of nature are linked phenomena that have featured among solitaries for centuries. But Lou’s bear is no deity. One night she is visited by the Devil who mocks her adoration of her ‘tatty old pet’. ‘Be a good girl, now, and go away. No stars will fall in your grasp.’

Lou ignores the warning. But when, a few days later, the bear finally accepts her invitation to mount her and wound her back, she awakens to his animality. If the bear smells her blood he will attack her. She chases him away. The encounter between them the next day is friendly but the sacred communion has dissolved. The bear is only an old bear. Yet something vital has passed from him to her. The ‘breath of kind beasts’ has been upon her. The sweet wild sex of solitude has worked its magic on her. She packs up and drives back to the city at night, feeling strong and pure, with the Great Bear shining down on her.

[i] The first paragraphs of this blog are adapted from my contribution to a feature, ‘Desert Island Texts’, that appeared in Women: A Cultural Review (2010).

Barbara Taylor is Professor of Humanities at Queen Mary University of London and Principal Investigator on the ‘Pathologies of Solitude’ project.