In space, as the tagline to Alien (1979) memorably put it, no one can hear you scream. But whilst it may be the vacuum of the interstellar abyss that prevents any sound from travelling, your screams (should you choose to emit them) might go unheard simply because there is no one around to listen to them. The first space flights were all solo affairs, from the Rhesus monkeys and stray dogs launched heavenwards by the US and the Soviet Union in test flights throughout the 1950s, to the single-occupant rockets of the US Mercury programme. Even in the cinematic universe, outer space often remains a solitary realm, the most recent example being Ad Astra (2019), in which Brad Pitt seemingly sends himself into celestial oblivion just to get some distance from the rest of the human race.

Ad Astra is by no means unique in its exploration of the radical disconnection wrought by interplanetary travel and the isolation of the space suit. Perhaps the most influential science fiction film of all time, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) contains extended periods of space seclusion. The film begins on a prehistoric Earth, then moves to the moon in the near future, and in both instances, we are privy to the workings of social groups: the familial bonds between hominids; the workplace camaraderie (and suspicion) of UN investigators of an alien signal. But once we board the Discovery One, bound for Jupiter (and possible extra-terrestrial life), the film turns colder.

The craft’s two crewmembers Bowman and Poole may interact with one another, but these exchanges are brief and, until disaster strikes, monosyllabic. They eat in silence and exercise alone. Their sentient computer HAL is far from taciturn, his amiable manner standing in for the humanity that seems absent from the people onscreen. When HAL turns homicidal, Bowman and Poole seal themselves in an escape pod and discuss what to do – but HAL reads their lips and plots against them, evidence of the danger of any social interaction. After Poole is killed, Bowman shuts HAL down in a scene in which the computer’s voice memorably stretches and distorts even as HAL insists on chatting away to prove its existence. Left again with peace and quiet, Bowman departs on a journey beyond time and space, and in the final moments of the film he surreally watches himself age, as though our own mortality is written on the faces of all those we meet.

Traces of 2001 can be found in Silent Running (1972), Gravity (2013), Ad Astra, and both versions of Solaris (1972 and 2002). In these films the protagonists are prickly, closed-off, unsympathetic. They go into space not because of cosmic curiosity, or even career ambition, but to stay away from people. In Silent Running, given the choice between people and plants, the protagonist chooses flora, killing his fellow crewmembers when they threaten the massive space-greenhouse to which he tends. In Gravity, the one-person habitat of the space suit is ideal for protagonist Ryan Stone, who wishes only to drift alone in the aftermath of her daughter’s death.

Deceased loved-ones also motivate the leads of Ad Astra and Solaris, as they venture into deep space for an encounter with some long-supressed trauma. In the early scenes of the 2002 Solaris we observe our twitchy lead Kelvin slumping his way through a monotonous routine, his profession as a counsellor a kind of cruel irony, as he deals with the suicide of his partner. Both this film and its original end with Kelvin seemingly becoming one with an alien intelligence, as though they have drifted so far from human connection that this is the only companionship available to them. Meanwhile, Ad Astra’s McBride is a self-appointed social outcast, a man whose very presence seems to lead those around him to wither and die. He looks to the void not for therapy but to be left in peace, agreeing to a dangerous interplanetary mission perhaps just to put an end to an awkward conversation. As the character states in voiceover, he is always looking for the exit door – and outer space is the ultimate exit.

If McBride vows ‘never to rely on anyone or anything’ as a marker of his fitness for interstellar duty, then by the end of the film he has slightly mellowed in his attitude. Cosmic emptiness is a place to visit, but you can always come home. The same is true of Stone, whose efforts to return to Earth render her socially active, nattering away to the ghost of George Clooney and an Eskimo on a malfunctioning radio as she rewires a space capsule. The plucky, can-do attitude she evinces by Gravity’s end is expanded upon in The Martian (2015), in which Matt Damon’s unwilling Robinson Crusoe Mark Watney must learn to survive for years on the red planet with only a few potatoes, some dung, and as much solitary badinage as he can muster.

The Martian’s Watney may be put through the hardships of only having access to disco music and Happy Days reruns during his downtime (thanks to the abandoned files of a former crew member), but in other films the solitude of space leads to more unnerving effects. The low-budget films Astronaut: The Last Push (2012) and Capsule (2015) confine themselves almost entirely to the interior of a single spacecraft, and while they mine drama from radio communications they emphasise the psychological pressure of utter individual autonomy. Meanwhile, Interstellar’s (2014) protagonist Cooper abandons his daughter to seek out new life and new planets, but ends up on a sterile ice world, lured by stranded astronaut Dr Mann, who cannot bear the thought of being alone in the cosmic wilderness for the rest of his life.

Mann, whose name suggests a cynical take on the species (or perhaps the gender), compulsively lies about the habitableness of his new home because he seeks a rescue mission which otherwise will never come. Played again by Damon, Mann is a chilling mirror-image of Watney, a self-serious person for whom the thought of a solitary existence (or death by his own hand) is worse than damning the entire human civilisation to slow starvation. He dies on the ice anyway, and even if Cooper himself ends up floating alone beyond the limits of space and time within the event horizon of a black hole, he still has a jocular robot for company, and is even able to send one way messages to his daughter several light years and decades away. Like a more saccharine version of Gravity or Ad Astra, the film’s abandonment issues are put to use proving the thesis that love, improbable as it may be, is the strongest force in the universe. Mann’s actions are in this way somehow rationalised, evidence of the compulsiveness with which humans will seek out one another.

In the somewhat darker Moon (2009), tired three-year-shift worker Sam Bell is looking forward to returning from his one-man resource extraction job on the lunar surface, only to discover that he is a clone and has never actually stepped foot on Earth. When another Sam Bell is accidentally awakened, the two of them work together to escape their fates as expendable corporate assets. Here, social atomisation is a tool used by multinational conglomerates, a method of controlling information and desire, and keeping us content with the daily grind.

A similar message appears in Wall-E (2010), as the titular trash-compacting robot’s toil on an apocalyptic Earth is interrupted by a trip to the spaceship-cum-luxury-liner Axiom. Like Bell, Wall-E realises that there’s more to life than work only through its interaction with others, and this interaction is capable of short-circuiting the capitalist system which aims to keep us apart. Social exclusion is not so much de-humanising in these films as it prevents our humanisation in the first place.

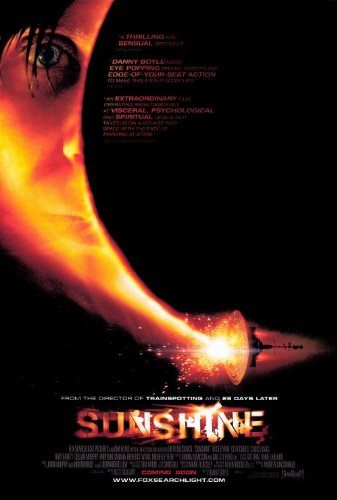

There’s outright horror in the void, too. At the end of Alien, all but one crew member has been killed off, and this survivor must face the titular xenomorph alone (although she does rescue her cat). A later game based on the franchise includes seclusion in its title – Alien: Isolation (2014) emphasises the single in single player, as the gamer tries to outwit an advanced AI foe using only their wits and meagre supplies. But what if we embraced the sublime possibilities of a universe emptied of people? In Sunshine (2007), in an effort to stave off a world-ending winter, a small international crew is launched towards the sun with an enormous nuclear bomb in tow. Along the way they accidentally pick up a stowaway – the lone survivor of an earlier mission, Captain Pinbacker. Having lived alone on an abandoned spacecraft for seven years, Pinbacker has become convinced that rather than save the human race he should allow it to die out, leaving him to be the only surviving person in the universe. ‘At the end of time, a moment will come when just one man remains,’ he states, flesh melting from his sunburned body, ‘then the moment will pass. Man will be gone. There will be nothing to show that we were ever here but stardust. The last man alone with God… Am I that man?’

Pinbacker, then, is the ultimate embracer of cosmic solitude. Characters like McBride, Stone, Bell and Mann are only tourists, and they certainly aren’t willing to stab and detonate anyone who gets in the way of their isolation. Even McBride’s absent father in Ad Astra forsook the human race to search for the more profound connection offered by alien life. Pinbacker sees divinity in absolute emptiness, and as the violent, unstoppable villain of the film he asks us to recoil from the mere thought of such radical exclusionism. Space may have the potential to be overwhelmingly lonely, but in most films this serves not as an opportunity to sever all human bonds but a chance to remind ourselves of their importance.

Unlike Laika, the famous dog who orbited the Earth in Sputnik 2 in 1957 and presumably died long before her capsule burnt up on re-entry months later, fictional astronauts for the most part come back down to Earth safely if bumpily, and ultimately serve as figureheads for the dangerous temptations of imposed loneliness.

Nick Jones (@nphjones) is Lecturer in Film, Television and Digital Culture at the University of York. His next major book, Spaces Mapped and Monstrous, is forthcoming in 2020.