In October 2018, the world’s first minister for loneliness, Tracey Crouch, published her strategy for tackling loneliness, called ‘A Connected Society’. In the accompanying press release, the Prime Minister’s office described the scale of the problem: ‘up to a fifth of all UK adults feel lonely most or all of the time’.

Theresa May was inflating the data in the strategy. ‘It’s estimated’, it wrote, ‘that between 5% and 18% of UK adults feel lonely often or always’. The higher figure was derived from a 2016 pressure-group study which concluded that 4% of those aged over fifteen always felt lonely, and 14% did so often. The lower figure was generated by The Office for National Statistics (ONS), which had conducted a re-analysis of its data as preparation for the strategy. When asked the question, ‘How often do you feel lonely?’, 5% of its sample replied ‘often/always’.

The gap between the official finding and the Prime Minister’s summary was eight million lonely people. The desire to endorse the more alarming calculation reflected the broader discourse. On the basis of an extensive literature review Keith Snell writes that ‘loneliness is now widely diagnosed as a modern ‘epidemic’ or ‘plague’ ‘.[i]

The most consistent evidence on loneliness relates to the elderly. It suggests that levels were at the lower end of the range in contemporary public debate, and that there has been no significant growth over two thirds of a century. Christina Victor concluded in 2002 that:

there appears to be little strong or compelling evidence to suggest that… rates of loneliness have increased markedly over time… Self-reported significant loneliness is experienced by about 5-15 per cent of the population aged 65 years and over and this has remained stable over the past 60 years.[ii]

In this context, the 2018 ONS ‘often/always’ figure of 5%, although relating to the whole adult population, does not look like an outlier.

Two questions therefore arise. The first is the nature of the rising concern about loneliness which has come to be seen as an emblematic pathology of our times. A combination of demographic, political, cultural, ideological and medical factors have together created a category of experience which in its outlines is as broad as the pathology of melancholy which was so widely deployed until the twentieth century.

The second question is what loneliness means. The most succinct definition of loneliness is failed solitude. This foregrounds the critical issue of the why, in the surveys since the 1940s, a substantial majority of people who are living alone do not report being lonely.

The Panic

Loneliness was initially identified as a problem during the Second World War when concerns about ‘morale’ focused attention on the experience of women whose men had been conscripted and whose children evacuated. The wartime discovery of loneliness expanded in two connected areas after 1945. Planning for the new society envisaged a growing problem of social relations amongst the elderly. Before 1900 the proportion of the population aged sixty-five and over was stable at between 4 and 5%. It began to grow between the wars to the current level of just over 18%. Research concluded that the lonely elderly varied in the intensity of their loneliness. At the core of the problem was bereavement. Peter Townsend found that ‘the underlying reason for loneliness in old age is desolation rather than isolation’.[iii] The destruction of health and spirits was a function of the irreversible loss of a long-term intimate partner.

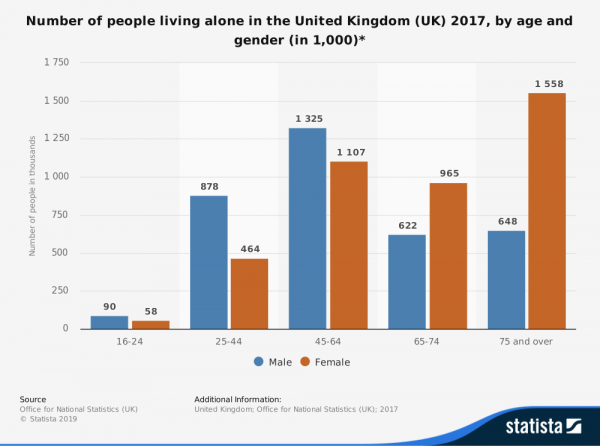

The qualitative research was reinforced by demographic change. The early twentieth century inherited a tradition of no more than 5% of single-person households containing 1% of the population. The incidence has now grown to 31%, embracing some eight million people.

The change was particularly dramatic amongst the elderly. By the late 1960s, a quarter of men and just over half of women aged sixty-five and over were living alone. Amongst this group the most common determinant of household structure was the transition to widowhood.

The second generator of concern was the programme of slum clearance. As the council estates took shape, investigators examined the consequences of the rapid change in urban living. The research reflected a growing concern that the forces of modernity were generating unanticipated problems of sociability. A combination of the welfare state and the post-war consumer boom was placing individual gratification at odds with intimate relationships. Loneliness was a visible symptom of an increasingly unmanageable tension between the pursuit of material comfort and the conduct of satisfying personal relations.

The resonance of loneliness was enhanced by developments in psychiatry. Interest grew in the impact of states of mind on physical wellbeing. Frieda Fromm-Reichmann introduced a new category of mental illnesses. ‘Real loneliness’, she explained, ‘…leads ultimately to the development of psychotic states. It renders people who suffer it emotionally paralyzed and helpless’.[iv]

Alongside the concern with psychological ill-health, what Judith Shulevitz has termed ‘the lethality of loneliness‘ has become the subject of widespread commentary. The government loneliness strategy stated that ‘its health impact is thought to be on a par with other public health priorities like obesity or smoking’. The alarmist language was dependent on the self-description of the target population in response to questionnaire surveys. There was no objective measure of suffering. Cigarettes could be counted, people could be weighed. However, in the case of loneliness the distinctions between severe and less severe remained for the most part a construct of the researchers, applying adjectival categories as a means of ordering their data.

There is no a priori reason why loneliness, as with any emotional state, should increase in step changes, however they are labelled and by whom. Nor, at a more granular level, does loneliness necessarily progress on a single scale. Some forms of the experience are not more or less, just different, from others.

A second complexity was the issue of causality. If there was an association of loneliness with failing health, it was not clear which was leading to the other. The recent, widely-cited literature review by Julianne Holt-Lunstad insists on an association between loneliness and morbidity, but is careful to leave open the direction of travel. There is also a confusion between reported direct consequences of loneliness and attention-grabbing analogies. Such claims can partly be explained by the dynamics of pressure group activity. Bodies seeking to raise funding and enhance their public profile associate themselves with the authority of campaigns which in the case of smoking go back over two thirds of a century. The pressure groups, however, are the product of a larger atmosphere of panic.

The constant tendency to fly to extremes of negative estimation has its roots in a wider apprehension about the failings of late modernity. The sense of crisis is manifest at two levels. In government, there is a concern that the lonely citizen is an unintended consequence of the necessary pursuit of individual gain in a society of weakening social networks. The new loneliness strategy revives David Cameron’s ‘Big Society’ project, thought by commentators to be long buried. For critics of the Conservatives’ approach, the challenge is more fundamental. Loneliness is the representative pathology of high modernity. It is not a niche social problem or a passing challenge to public policy, but reflects the comprehensive inability of contemporary forms of intimacy to withstand what George Monbiot describes as ‘competitive self-interest and extreme individualism‘.

Loneliness and solitude

In the discourse about loneliness, solitude appears as a double negative. It is the condition of those who are not in company and who are not feeling alone. The experience is infrequently addressed by name, despite the fact that it constitutes the majority of responses in most surveys. It may be argued, however, that the impact of late modernity on social relations lies at the boundary between solitude and loneliness.

The steep growth of single-person households since the Second World War has fuelled much of the current sense of crisis. However, a succession of surveys has challenged the association between the physical condition of living alone and the emotional pain of loneliness. The elderly were for the most part exploiting opportunities rather than suffering deprivation. The fear of losing independence was a more powerful force amongst the elderly than the fear of loneliness. Amongst younger cohorts there was a wider range of needs and circumstances, but common to all was the capacity to determine how to live. Improvements in domestic space, household prosperity and communication systems expanded the pastimes which engaged attention in the absence of company.

Living alone was less a pathology of late modernity and more a frequently valued consequence of its defining strengths. The question is under what circumstances solitude tipped over into loneliness. The central issue is not demography but choice. Seeking to make space for yourself within a relationship or withdrawing from it altogether, have always been strategies for living. They were calculated risks which did not always result in intended outcomes.

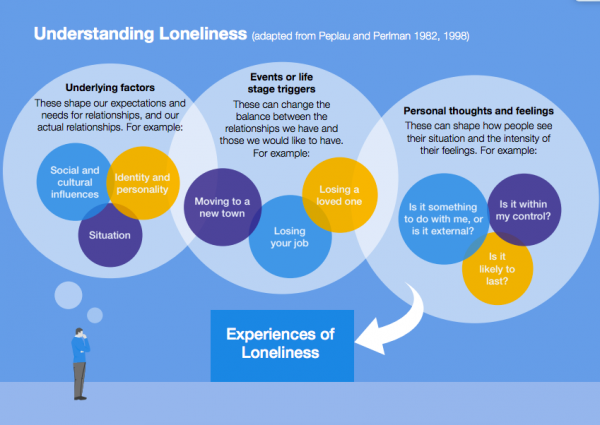

Time was a critical factor. One definition of loneliness is that it is solitude which has continued for longer than was intended. Recent research has suggested that the condition represents a U-shaped curve, with the peaks amongst those in their early and concluding years. This finding is related to the number of transitions in most people’s lives. At the beginning of the modern period, there were likely to be few significant changes in an individual’s social or economic circumstances. By contrast, late modernity has seen a multiplication of what the government’s loneliness strategy describes as ‘trigger points’ and with it an expansion of the range of choices about forms of sociability that need to be made.

Consideration of the often porous boundary between loneliness and solitude generates two broad conclusions. The first is that loneliness in some form is not exclusively the product of the failings of late modernity. The major change that has taken place is in the multiplication of educational, occupational and geographic movements and the increasing diversity and instability of intimate relationships. In this sense, the argument of the more alarmist accounts of loneliness that it is becoming a near universal experience have substance. The question rather is the depth of the suffering which it entails. Loneliness in this sense has become woven into the human condition, integral to the strategies for living that all have to negotiate, and that almost all fail at some point to manage successfully.

The second conclusion is that the association of loneliness with the failings of late modernity lay less at the interface between intimacy and individualism, and more in the incidence of material inequality and the failures in the public finances that have become more pronounced since the financial crash of 1998. In one way or another, the post-war expansion of forms of recreational solitude were a function of increasing household prosperity, better access to communication systems and the introduction of a welfare state. The difficulty of enjoying solitude whilst containing loneliness increased as personal and collective prosperity fell.

Recent United Nations data suggests that fourteen million people, over a fifth of the population, are in poverty and one and a half million are destitute. Deprivation has impacted directly on solitude with regard to inadequate housing, insufficient surplus cash to spend on personal pastimes, and exclusion from physical and virtual mobility. The poor are also less likely to have access to the social and medical services which can relieve the experience or threat of loneliness.

The post-1998 austerity programme challenges any attempt to develop a government strategy in this field. But with the state unable to spend significant sums on welfare and continuing disinvestment in critical facilities such as public libraries and adult social services, the prospect of an effective, integrated attack on even the more acute forms of loneliness seems remote.

Loneliness has become a proxy not so much for the contradictions in the social relations of our times, as for the intensifying crisis in the distribution of wealth and the management of public services.

[i] Keith Snell, Spirits of Community: English Senses of Belonging and Loss, 1750-2000 (London: Bloomsbury, 2016), p. 1.

[ii] Christina Victor, Sasha Scrambler and John Bond, The Social World of Older People (Maidenhead: Open University Press, 2009), p.204.

[iii] Peter Townsend, The Family Life of Old People: an inquiry in east London (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1957), p. 182.

[iv] Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, ‘Loneliness’, Contemporary Psychoanalysis 26 (2009), pp. 305-29 (p. 309).

David Vincent is Emeritus Professor of History at the Open University. His next major book, A History of Solitude, is forthcoming in 2019.