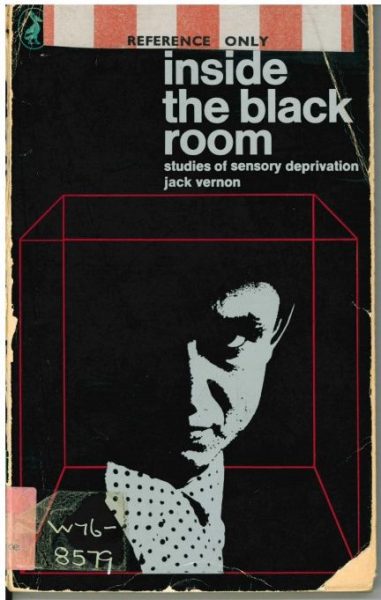

Even the most familiar faces may appear unrecognisable in an unfamiliar setting. Certainly, I had to do a double take when I first came across Jack Vernon’s Inside the Black Room (1966) in London’s Senate House Library. I had visited the library to look up material related to Cold War human experiments in sensory deprivation. It seemed an unlikely place to find a portrait of the country music icon Johnny Cash.

The effects of isolation on the human mind have long fascinated psychologists, philosophers and artists. But it was during the Cold War that isolation, or at least a version of it, came under considerable scientific scrutiny. For a brief period in the 1950s and 1960s, sensory deprivation (SD) research was an established and well-respected field in North American behavioural sciences. SD experiments set out to examine the effects of a severely reduced stimulus environment on the human mind and had theoretical applications related to brain physiology, perceptual, motivational and psychoanalytic theory as well as clinical and practical applications.

After a brief heyday, the discipline all but disappeared in the 1970s as critics drew links between the military funding that supported much of this research and techniques of psychological torture. Of the dozen or so texts on sensory deprivation at Senate House, former Princeton professor Jack Vernon’s Inside the Black Room was the only one targeted at a non-specialist audience. That such an audience should exist was hardly surprising. SD experiments had appeared in films such as The Mind Benders (1963), The US television series The Twilight Zone (1958), and on the BBC’s A Question of Science (1957). Each of these, with greater or lesser degree of sensationalism, set out to examine its supposed mind-altering effects.

Fascination with sensory deprivation at the time was captured by Vernon’s copywriters, who wrote on the back cover:

What happens to a man when all sensory stimulation is cut off for a certain period time?… These questions are vital in a world concerned with space travel, solitary confinement and brain-washing?

But, for me, the front cover of this edition posed an entirely different and unexpected question: What was Johnny Cash doing on a popular psychology text from 1966? Curiosity, or procrastination, having got the better of me, I was able to find the original image by photographer Don Hunstein (1928-2017) online, who served as Director of Photography at Columbia Records for over 30 years. After making an inquiry through a website dedicated to his work, I received a response from Don’s wife DeeAnne.

DeeAnne informed me that Don had been a good friend of the graphic designer Germano Facetti, who often used Hunstein’s images on covers for Penguin books. Facetti’s decision to put Cash on his cover was perhaps more than opportunistic. As head of design at Penguin, Facetti is remembered for transforming the publisher’s art direction during his tenure (1960-1972) and gained a reputation for his ability to capture the essence of a book with a single image, providing what he described as, ‘a visual frame of reference to the work of literature as an additional service to the reader.’ In this case the subject was Jack Vernon’s ‘black room’, a sophisticated light and sound proof chamber in the basement of Princeton’s Eno Hall.

One of Vernon’s student volunteers described their first experience inside this space:

I entered the cell that was to become the deepest darkness I have ever known.

In Facetti’s monotone image, Cash can be seen either disappearing into or re-emerging from this sensory void, evoking a sense of mystery about what lies within and the changed person that might emerge from the chamber. The three dimensional cube enclosing the portrait adds to the sense of literal and psychological confinement, but may also refer to the red geometric shapes many subjects claimed to hallucinate whilst inside the chamber. One of the surprising results of sensory deprivation research from this period was that without visual referents or patterned stimuli, the mind appeared to spontaneously generate images of its own.

Part of the early fascination with sensory and perceptual deprivation experiments revolved around whether, in this disoriented state, the subject could be made more suggestible, susceptible to indoctrination – or in the parlance of the time ‘brainwashing’. That Vernon’s aforementioned student should choose the word ‘cell’ – as opposed to ‘chamber’ or ‘room’ – to describe the experience is suggestive of the ways in which volunteers may have consciously or unconsciously associated SD experiments with imprisonment.

In Inside the Black Room, Vernon describes another student who made this association explicit. Having stayed in the chamber for the maximum of four days, the politics student requested to stay longer. On further questioning the student revealed that he felt there was a high chance that he may one day end up as a political prisoner when he returned to his native Turkey, and that he wished to train himself to be able to tolerate solitary confinement.

The association between SD and the prison provides the most likely explanation as to why Facetti chose to put Cash on the cover of Vernon’s book. When the Penguin version was published in 1966, Cash had already gained a reputation for singing about and sympathising with the experience of incarceration in the US penitentiary system. Whilst early hits such as ‘Folsom Prison Blues’ (1955) and ‘Transfusion Blues’ (1960) contrasted a romanticised image of a care-free and cold-hearted outlaw with a life of confinement, later songs such as ‘San Quentin’ (1969) and ‘The Man in Black’ (1971) took direct aim at prison conditions, treatment of prisoners and US policies of incarceration.

But Cash’s most memorable interactions with the American prison population came during the numerous concerts his band performed inside prison walls, preserved in two successful albums, ‘Live at Folsom Prison’ (1968) and ‘Live at San Quentin’ (1969). At San Quentin, Cash sang, for the first time, a song named after the prison about the destructive experience of incarceration. Lyrics such as ‘San Quentin, I hate every inch of you/ You’ve cut me and you’ve scarred me through and through/’, were met with raucous applause from the audience who demanded a second rendition immediately after Cash sang the first.

On the ‘Live at Folsom’ record, Cash can be heard striking a more optimistic tone with ‘Grey Stone Chapel’, a song written by Folsom inmate Glen Sherley who was sitting on the front row. The songs refrain ‘inside the walls of prison my body may be/ but the lord has set my soul free/’ describes the role of religious devotion in the struggle for the free mind within an incarcerated body – a topic of central interest to our research project.

Cash’s prison concerts were performed against a backdrop of scandals, public outrage and calls for reform within the US prison system, of which he became a leading spokesperson. In 1972 he even gave evidence alongside former convicts at a Senate hearing on prison reform, where he relayed some of the worst stories of corruption and abuse inmates had told him.

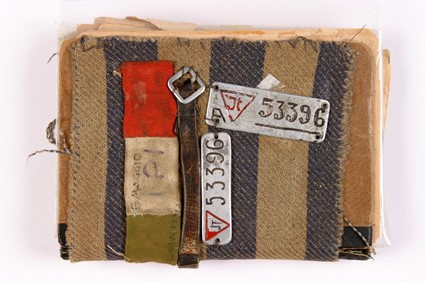

Despite the outlaw image he cultivated, Cash himself never spent more than a night in a jail cell. The graphic designer who used his image on the other hand had experienced a horrific period of captivity during the Second World War. Captured as an armed member of the Italian resistance in 1943, Facetti was deported aged 17 to a labour camp in Mauthausen Austria, where 100s of prisoners died each day at the hands of the Nazis. After the camp was liberated in 1944, he gathered drawings he made alongside photographs and documents salvaged from the camp in a small box.

Bound together with fragments of his prison uniform and identification tags, the box is the subject of a short documentary, The Yellow Box, by Tony West. Facetti could not have known in 1966 that Cash would go on to have such an influence on US prison reform. Perhaps, however, he hoped that like Cash’s music, and like his own yellow box, Inside the Black Room might shed light on the experience of the incarcerated.

To what extent sensory deprivation experiments have contributed to the scientific understanding of incarceration is a complicated question. Early research, particularly the perceptual deprivation experiments carried out at McGill University in the 1950s, suggested that the effects of inhabiting a depatterned environment were inherently pathological. Certainly, studies in this area have shown that under the right conditions SD can induce high levels of anxiety, depersonalisation and perceptual distortion. Such data has often been used by critics of solitary confinement as well as methods of psychological torture such as the ‘Five Techniques’ used by the British Army in Northern Ireland or the methods of so called ‘enhanced interrogation’ used at detention centres such as Guantanamo Bay.

But other research into this field has shown that under the right conditions sensory isolation can have therapeutic potential. Flotation tanks, for example, once seen as a faddish new-age trend, are undergoing clinical trials as a treatment for both acute and chronic mental disorders. In fact, research on SD from the 50s and 60s has shown that the technique can produce a diverse range of responses which depend on a complex ecology of interacting variables, some of which are beyond the control of the experimental situation. The subjective experience of SD is not only influenced by the physical and temporal dimensions of the experiment, but also on the subject’s personality, mood, physiology and various other social and cultural factors.

SD experiments have given some insight into the unusual effects of extreme isolation, but we should be cautious when attributing these results to the significantly different experience of involuntary incarceration or other forms of isolation. Understanding these experiences often requires a far wider lens than the experimental setting can provide, taking into account broader psychological, social, and cultural factors. Perhaps, after all, Facetti’s choice of Johnny Cash on his front cover reminds us of the need to pay attention to the individual stories and experiences of incarceration and solitude and the complex histories that shape them.

Charlie Williams is a postdoctoral research fellow on the ‘Pathologies of Solitude’ project at Queen Mary University of London.