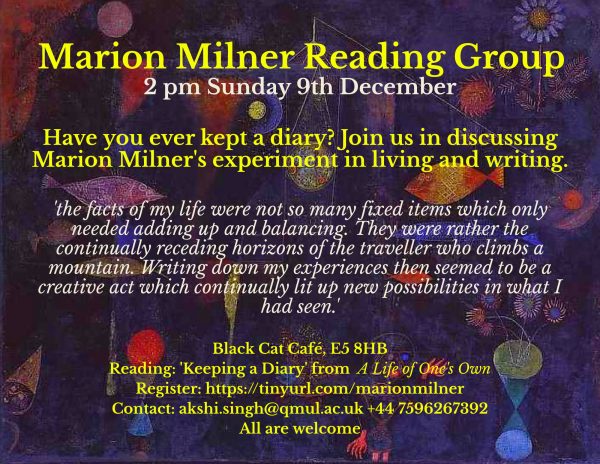

We were walking across Hackney Downs. For the past two hours, we had sat in a café, reading the second chapter of Marion Milner’s A Life of One’s Own. In ‘Keeping A Diary’, Milner describes her experience of attempting to record her desires, and moments of happiness. Milner’s commentary is interspersed with generous extracts from her diaries, and we soon learn that what she writes is not confined to accounts of want or joy. The very first diary entry she quotes in this chapter says only: ‘rather oppressed with the number of things to be done’.

Walking, we spoke of what we’d just read. My companions and I were all diary-writers, and we’d been friends for some years. We’d seen each other write and understood, at those moments, to not interrupt. I think we were all surprised to find that Milner’s chapter on diary keeping had left us with an unexpected sense of relief and freedom.

Milner records details that seem mundane: ‘I was thinking about my new frock and shoes’ or, ‘no impulse to write, cold in the head, constipated, too much to eat’. The ordinariness of these entries led us to notice that there had been an unspoken injunction operating when we sat down to write our diaries – the demand that we write something of significance, that we reckon with our inner selves.

Writing a diary is widely considered a private act. That said, it is also a practice that draws attention to the dialogues we engage in when alone, conversations with the others who shadow our solitude. Who are we writing to? Who do we want to exclude when we close our diaries and put them away? And who stands over our shoulder, judging what we say? In his essay ‘Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego’ Freud wrote:

in the individual’s mental life someone else is invariably involved, as a model, as an object, as a helper, as an opponent.

Perhaps the question of solitude then is also the question of who accompanies us in our solitary moments.

My friends and I discovered that we shared our moments of solitary diary writing with a rather bossy presence who demanded we put on our best intellectual clothes when writing. A dominating figure who didn’t want to be seen thinking of digestion. Maybe that is why our diaries often lay neglected for months on end – because it wasn’t much fun hanging out with this judgmental character. But here Milner was, encouraging us by example to allow ourselves our inconsequence.

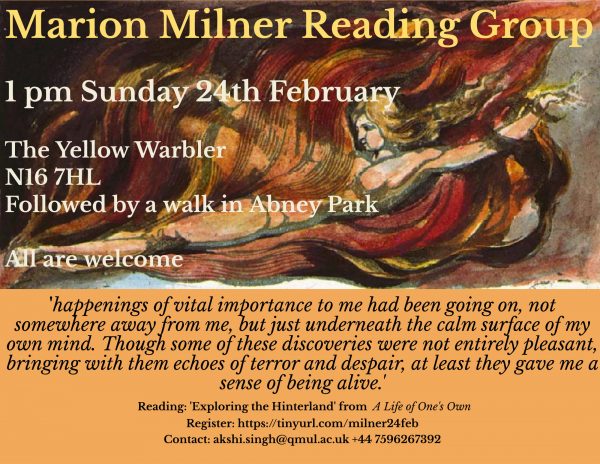

As she writes, Milner begins to discover that ‘possibly the thing that matters, the you are looking for, is like the roots of plants, hidden and happening in the gaps of your knowledge’.

What Milner is looking for, as the title of her book indicates, is a life of her own. She has varied ways of conjugating this: ‘a standard of values that is truly one’s own and not a borrowed mass produced ideal’; ‘trying to live one’s own knowledge’; ‘knowing with the whole of my body’.

At stake in Milne’s project is the question of solitude as the capacity to think for oneself, to recognize and take responsibility for one’s desires. Also involved is solitude as discovery—of fears, pleasures and wants that emerge when we are alone. And yet, as Milner’s writing suggests, these explorations of solitude are closely tied to relationships with others—more often than not, others who are not even embodied, let alone physically present at the scene of writing.

Sometimes these are people are the imagined voice of a collectivity. Milner writes:

One day I’ll make a list of points of conflict with the herd. One is – ‘They’ assume that what happens is what matters, where you go, what you do, things that happen, the good time that you have. But often I believe it’s none of these things, it’s the times between, the long days when nothing happens, the odd moments, perhaps when you open a letter, or sit alone in a restaurant, or exchange the time of day with a stranger…

Here Milner is thinking against the collective voice of public opinion – ‘the herd’ – to discover her own opinions, and the things that matter to her. But this is not ‘thinking’ as concentrated effort. Later in the book Milner will note that she ‘had been brought up to believe that to try was the only way to overcome difficulty’ and that it was a challenge for her to give up this attitude of effort. Milner’s discovery of herself is connected with letting go of the effortful, watchful self, and entrusting herself to a part of her that by knowing less, can find out more: ‘only when I stopped thinking would I really know what I wanted’.

Milner allows solitude to be an adventure, and one amongst many rewarding paradoxes that we can take away from her writing is that experiences of solitude are shaped by the company we keep when we are alone.

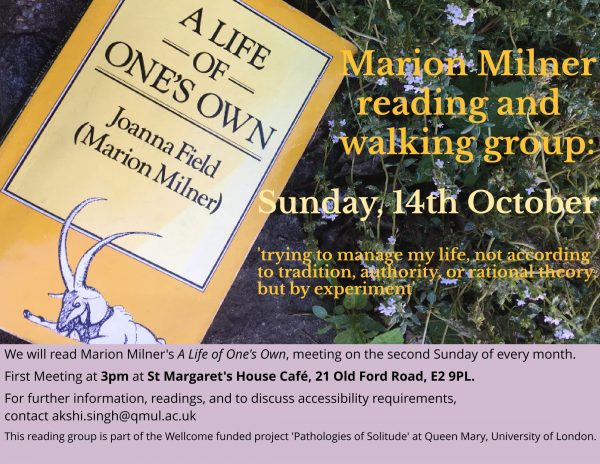

The Marion Milner Reading and Walking Group meets once a month, on a Sunday. All are welcome.

Akshi Singh is a postdoctoral research fellow on the ‘Pathologies of Solitude’ project at Queen Mary University of London.